Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

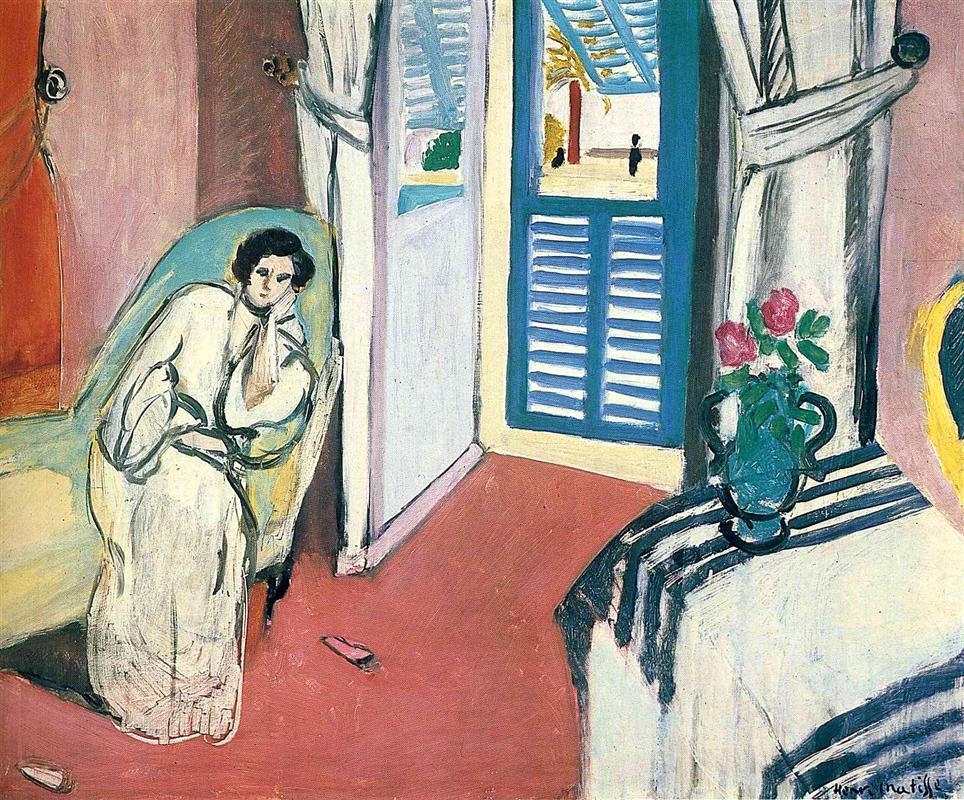

Henri Matisse’s “Woman on a Sofa” (1919) stages a quiet drama of color and light inside a Nice apartment. A woman in a white robe leans into a turquoise armchair at the left edge of the canvas, her head propped on her hand as if suspended between daydream and observation. The red-coral floor pushes toward an open doorway with blue shutters, where a sliver of promenade, palm, and sky glows beyond the balustrade. At the right a striped cloth and a green jug of roses offer a counterweight to the figure. Nothing monumental happens, yet the room vibrates with purpose. Matisse turns a handful of simple elements—sofa, slippers, shutters, vase, and light—into a poised architecture that invites prolonged looking.

The Nice Period and the Return to Clarity

Painted during Matisse’s first postwar seasons on the Côte d’Azur, the picture belongs to a pivotal shift in his art. Rather than the blazing provocations of Fauvism or the restlessly experimental structures of the 1910s, he sought in Nice an ethic of clarity. Interiors became instruments for measuring light; decoration served as skeleton rather than ornament; figures were placed as tones in a carefully tuned chord. “Woman on a Sofa” is exemplary of this approach. It offers calm without dullness and silence without emptiness, the kind of sustained serenity the artist believed painting could provide at a time when Europe was hungry for coherence.

First Impressions and Motif

The motif is both domestic and theatrical. A woman dressed in white occupies the left margin, compressed into the broad arm of a sea-green chair. Two pink slippers rest on the red floor as if they had been kicked away casually, coming to a halt at different angles. The central axis is a doorway with blue shutters, partly open, admitting a view of the outside world. To the right a table draped with a black-and-white striped cloth carries a green jug with two pink roses. Curtains are pulled aside like stage wings, loops of tie-backs anchoring them at the wall. Matisse builds a space that feels lived-in but composed, private yet pointed toward the public promenade outside.

Composition and Spatial Design

The composition pivots on a triangle that runs from the seated figure to the open doorway and back along the striped cloth to the foreground. The floor plane, laid in with a single sweep of coral red, operates like a tilted stage leading the eye toward the balcony threshold. Overlap replaces linear perspective: chair before wall, figure before chair, curtain before doorjamb, shutters before the world. These layers create a shallow, habitable space that never abandons the flatness of the painted surface. The narrow corner where two walls meet, just left of the doorway, becomes a fulcrum around which every element turns. The room is designed, not documented.

The Role of the Open Window and Shutters

Matisse’s Nice pictures often hinge on windows and balconies. Here, the blue shutters perform several jobs at once. They frame the slice of outside, calibrating interior light against Mediterranean air. Their slats echo the stripes of the tablecloth across the room, setting up a rhythm that ties left and right halves of the composition. Their cool blue opposes the warm coral of the floor, providing a chromatic breeze that keeps the room from overheating. Beyond the shutters a tiny scene—the palm trunk, a yellow building edge, small silhouettes of strollers—offers the faintest hum of narrative without diverting attention from the interior chord.

Color Architecture and Temperature

The painting is built from three principal color families: warm coral-red on the floor, cool blue in shutters and door, and a range of whites and off-whites in gown, walls, and curtains. Secondary notes supply counterpoint: the sea-green of the armchair, the black-and-white of the striped cloth, the deep green jug, and the fresh pink roses. Because the warm and cool families each appear in multiple zones, harmony replaces description. The woman’s robe, for instance, is not merely white; it is a field where cool notes from the shutters and warm reflections from the floor trade places, so that the fabric breathes. The coral ground gathers the composition into a single temperature and functions as a reservoir from which small pink accents—the slippers, the roses—seem to be drawn.

Light and Atmosphere

Light in “Woman on a Sofa” is Mediterranean but measured. There are few cast shadows; forms turn by temperature shifts and by the weight of contour. The curtains and robe carry soft bluish grays, as if touched by sea air. The floor glows more than it shines, its pigment mixed to a matte warmth that sustains the room’s gravity. The distant scene beyond the shutters is brighter and more bleached, reinforcing the sensation that outdoor light is stronger and whiter than the interior light that has been moderated by architecture and cloth. The result is a breathable atmosphere that is neither dramatic nor dull, exactly the middle climate Matisse sought.

Drawing and the Living Contour

Matisse’s black line—elastic, decisive, and humane—structures the whole. It articulates the curves of the chair, the knot of the curtain tie-backs, the stiff slats of the shutters, and the folds of the robe. The contour thickens and thins in response to need: firmer around the sleeves, lighter at the cheek, emphatic where floor meets wall. Because line remains visible, color never dissolves into decorative fog; forms keep their clarity even where paint is thin. The woman’s face is rendered with minimum marks—eyelids, nose bridge, small mouth—enough to register a mood of watchful repose without trapping the image in psychology.

Pattern as Structure

Decoration in this interior is structural. The tablecloth’s stripes operate like a musical stave, anchoring the right side with repeated dark and light bars. The shutters deliver a matching beat in their horizontal slats, a rhythm that leaps the doorway and establishes a pulse across the room. Even the metal curtain tie-backs serve as patterned nodes—small roundels placed high that balance the darker round base of the green jug. Pattern helps the space stay navigable without depending on detailed depiction of objects.

The Vase of Roses and the Grammar of Accents

The green jug and its two roses exemplify Matisse’s grammar of accent. The jug’s dark body creates the room’s deepest value, grounding the right side like a bass note. Its handles, drawn with looping confidence, echo the curves of the armchair where the woman sits. The roses deliver two compact bursts of saturated pink that repeat the slippers on the floor and the warmer passages outdoors. These small signals sharpen the eye’s path and keep the composition from resting too soon. The flowers are not botanical portraits; they are chromatic punctuation.

The Slippers and the Drama of the Floor

The two pink slippers scattered across the coral ground do more than suggest the occupant’s casual presence. They create a small narrative of movement—shoes removed, body relaxed—and form stepping-stones for the eye as it travels from the left margin toward the threshold. Their angles counter the strict geometry of the doorway and the stripes, softening the march of perpendiculars. In a painting that rejects anecdote, they are the perfect amount of human trace: enough to warm the room, not enough to demand a plot.

The Figure: Gesture Without Psychology

The woman’s pose is essentially architectural. Her body leans to echo the diagonal pull of the floor; her head props in the crook of a hand, forming a compact loop of arm and cheek that keeps attention near the chair. The robe’s belt simplifies the torso into broad planes. Because her expression is reduced, the figure is freed from portrait obligations and becomes a tone within the composition—a warm-cool white that binds shutters to curtains, table to door, and inside to outside. She is not a subject in the literary sense; she is the pivotal color that allows the interior to settle.

Rhythm and the Eye’s Path

The painting encourages a looping route. Many viewers begin with the figure, follow the chair’s turquoise curve down to the slippers, cross the coral field to the doorway, climb the blue shutters and pass briefly into the sunlit slice of promenade, then return along the right edge where the striped cloth and jug are waiting. The stripes tilt you back toward the figure; the roses nudge you into the coral again; the eye keeps circling. This rhythm is the painting’s substitute for narrative development. Instead of an event unfolding, a balance sustains itself over time.

Relationship to Related Works of 1919

“Woman on a Sofa” belongs to a cluster of Nice interiors from 1919 that test different weights of red, blue, and white and different degrees of window openness. Some versions feature a violin case or a mirror reflecting the bed; others place a model on a couch or present a standing figure by a shuttered door. What distinguishes this work is the spareness of its elements and the poise of its floor. The coral plane is more commanding here, and the figure sits at the edge like a consonant pressed lightly against a line of verse. The painting converses with contemporaneous balcony scenes, too, sharing their shutters and glimpses of sea, while choosing to stay firmly indoors.

Materials and Likely Palette

A compact palette gives the canvas its authority. Lead white supplies the body of curtains, gown, and pale walls. Yellow ochre and raw sienna warm the floor and the outdoor masonry when mixed with red lake or cadmium red to reach the coral register. Ultramarine and cobalt blues structure shutters, shadowed whites, and the small exterior sky; the shutters’ blue is adjusted toward green to harmonize with the armchair. Viridian or a blue-leaning green builds the jug and chair cover, sometimes deepened with black for accents. Ivory black is restricted to contouring and to the powerful bars of the striped cloth. Paint handling is mostly opaque with swift scumbles that allow the ground to breathe, especially in the robe and curtains.

How to Look

Stand first at the left edge and study the drawing of the figure. Notice how the outline of the arm is a single confident curve and how the inner lines of the robe describe structure with the gentlest insistence. Step onto the coral and test the direction of the two slippers—they point you toward the door. At the threshold, let your eyes rest in the cool of the blue shutters and then glance out to the tiny silhouettes in the sun. Retreat along the right edge and feel the pull of the black stripes; follow them back into the room, where the green jug holds its ground and the roses brighten the air. Repeat the loop. The painting deepens with each circuit, not by revealing hidden details but by tightening its correspondences.

Why the Painting Endures

“Woman on a Sofa” endures because it offers a modern answer to an old question: what can painting do for a viewer’s day? It can construct a room where color is proportioned exactly enough to calm the eye without dulling it, where light is moderated so whites remain open, where pattern is firm but not stiff, and where a human presence anchors the chord without insisting on story. The picture is generous without being busy, and simple without being thin. It proves Matisse’s conviction that painting can be a “good armchair” for the tired mind—though in this case the armchair belongs both to the woman and to the viewer who lingers.

Conclusion

In this interior Matisse orchestrates a handful of planes into a durable harmony: coral floor, blue shutters, white robe, striped cloth, green jug. The figure rests on the sofa the way a note rests within a chord—indispensable, suffusing the whole but not dominating it. Outside the shutters a palm and a few tiny strollers whisper of the Mediterranean, reminding us that the world continues beyond the room. Inside, color and contour keep time. The painting’s poise lies in its refusal to choose between leisure and attention: it gives you both at once.