Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

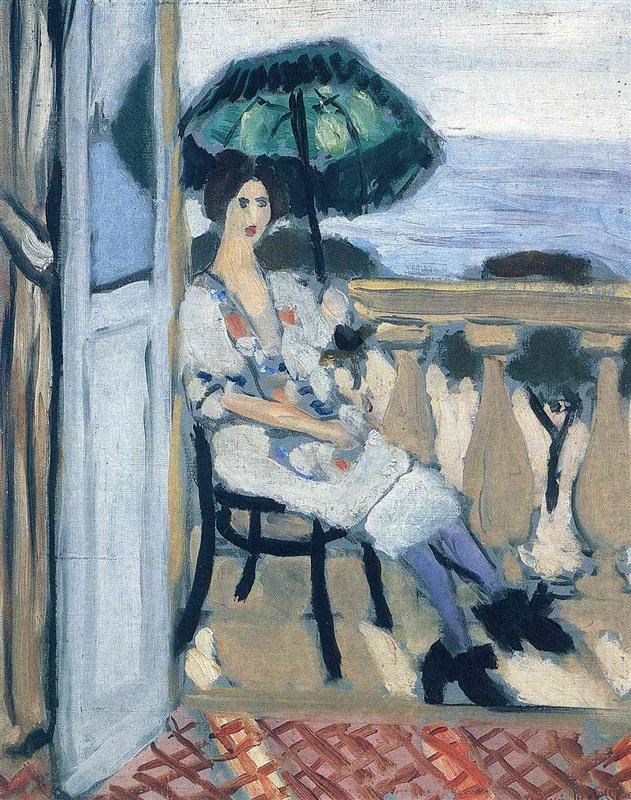

Henri Matisse’s “Woman Holding Umbrella” (1919) unfolds on a sunlit balcony in Nice, where interior hush meets the maritime blue of the Mediterranean. A seated woman occupies the shallow space between an open door and a heavy balustrade, a green parasol arcing above her head like a portable canopy of shade. The floor near the threshold flashes a lattice of reddish tiles, while beyond the stone rail the sea stretches in quiet bands. With a handful of large planes—door, figure, balcony, water—and elastic black contours, Matisse composes a scene that feels both immediate and distilled, a moment of rest calibrated by color and light rather than anecdote.

The Nice Period Setting

Painted during Matisse’s first postwar seasons in Nice, the picture belongs to a pivotal shift in his art. Having explored fauvist heat and analytic experiment in the previous decades, he turned in 1919 to a language of clarity and calm. Interiors became measured theatres of light; decoration served as structure; and figures were presented less as psychological portraits than as elements in a balanced chord of planes and temperatures. In this canvas, the balcony acts as a hinge between room and sea, and the parasol becomes the pictorial tool that lets him hold sunlight at bay without dimming color.

First Impressions and Motif

At first glance, the painting reads as a set of interlocking rectangles trimmed by curves. The left edge is seized by the pale blue of an open door. The right edge is anchored by the heavy ochres of the balustrade. Between them the figure settles into a dark chair, her light dress flecked with small blossoms, her stockings a cool violet, her shoes and parasol ribs stated in black. The green umbrella hovers like a leafed crown. Behind it, the horizon is reduced to a pair of undulating bands: slate-blue sea and bleached sky. Underfoot, the floor tiles assert themselves with a red lattice that announces the threshold as stage.

Composition: Frames, Stage, and Overlap

Matisse composes with a theater maker’s discipline. The doorway and the balustrade behave as wings, pressing the scene inward and protecting the gaze from spilling into open distance. The diagonal spread of the tiled floor leads the eye into the picture, but depth is quickly checked by the seated figure, whose knees point toward the right rail. Overlap, not perspective, builds space: door before woman, woman before chair, chair before balusters, balusters before sea. These layers maintain the painting’s flat objecthood while still delivering a convincing place we feel we could step into.

The Parasol as Pictorial Engine

The umbrella is no mere accessory; it is the key to the image’s balance. Its deep green disc compresses the vertical between rail and sky, providing a cool canopy that lets the warm stone and reddish tiles glow without glare. Internally, thin ribs articulated in black give the disc a hard-soft tension—structured shade rather than amorphous color. The staff repeats the verticals of the doorway and balusters, tying object to architecture. By siting the parasol just inside the balcony’s air, Matisse creates a mobile patch of shadow that organizes every other temperature.

Color Architecture and Temperature

The palette is determined and economical. Cool families dominate: powdered blues in door and sky, sea-blues shifting toward slate, blue-greens in the parasol, and lavender notes in stockings and ground shadows. Warm families answer: ochre-beige in the balustrade, a cinnamon note in the tiled floor, small pinks and reds in the dress’s pattern and lips. Black is used sparingly but decisively for contour, shoes, chair, and umbrella ribs. Because each color family recurs across different substances—blue as door, water, and air; ochre as stone and light—coherence replaces description. The harmony is temperature-driven; the picture breathes coolness edged with warmth.

Light: Measured Mediterranean

Light here is Riviera midday moderated by architecture. There is no theatrical spotlight, only a steady illumination that recedes at the doorway and ripens on stone. Volume is announced by temperature rather than tonal drama: the balusters swell from cool gray to creamy ochre; the dress turns with hints of violet and green where shade gathers; the umbrella absorbs the sun into a deep, vegetal tone. This measured light keeps contours legible, prevents whites from chalking, and allows the parasol to perform its structural task without reading as a black void.

Drawing: The Living Contour

Matisse’s drawing is frank and elastic. Strong black lines map the chair’s legs, the shoe profiles, the parasol ribs, and the doorway’s edges. Elsewhere the contour softens—around the face, at the dress’s sleeves—so that paint can complete the form. Line does not imprison color; it partners with it. The woman’s features, defined with a few strokes, avoid anecdotal detail yet register presence. In the balustrade, quick linear accents clarify the swelling profiles of stone spindles, keeping the middle ground buoyant and transparent rather than heavy.

Pattern as Structure

Decoration in this work is structural, not accessory. The red lattice on the floor tiles acts like the proscenium line in a theater, anchoring the lower edge and guiding the eye into depth. The small floral notes on the woman’s dress add flicker to the broad light plane of fabric, preventing it from flattening into blankness. Even the parasol’s ribbing is a patterned order that echoes shutter slats and baluster stems in other Nice pictures. Pattern thus does the quiet work of scaffolding space while feeding the picture’s rhythmic pulse.

Space: Shallow, Habitable, Designed

The balcony provides a short run from threshold to rail, and Matisse exploits that brevity. Space is neither deep nor claustrophobic; it is precisely enough to seat a body and expose it to air. The door at left keeps us within the interior’s cool; the rail offers the promise of a vista while still holding us in. Because each plane is also a distinct color field, we never forget we are looking at a flat painting; yet the sequence of planes—a designed procession—lets us imagine the weight of the chair, the density of stone, the breeze touching the sea.

The Figure: Poise Rather than Narrative

The seated woman is not offered as a character in a story. Gesture is minimal: hands rest, legs extend, head turns slightly. Expression is generalized, built from a few strokes that mark eyes and mouth. Presence arises instead from placement and relation: the body is comfortably lodged between door and rail; the parasol’s green shelters face and torso; shoes press against the tiled ground with pragmatic weight. The mood is leisure without idleness, a pause shaped more by climate than by emotion.

The Balcony as Modern Proscenium

Throughout the Nice period, Matisse used balconies and windows to reconcile his devotion to flatness with his love of view. Here the proscenium metaphor is clear. The doorjamb and curtain are like stage wings, the balustrade a front rail, the sea a painted backdrop. The woman is the performer of stillness. This mise-en-scène is not coy stagecraft; it is a lucid way to place forms so that a painting can remain a designed surface while admitting the sensation of air and distance.

Rhythm and the Eye’s Path

The canvas encourages a repeatable loop of looking. Many viewers enter at the red lattice, follow it diagonally into the scene, hit the black of the shoes, ride the leg to the dress’s pale field, climb to the pink lips and dark hair, lift into the green disc of the parasol, float out across the blue bands of sea and sky, and return along the ochres of the balustrade to the tiles again. Each circuit strengthens rhymes: green disc to blue sea; black shoe to black ribs; red lattice to small dress blossoms; cool door to cool sky. Rhythm, not narrative, sustains attention.

Brushwork and Surface

The paint handling is candid and varied. Doors and sky are laid in with broad, semi-opaque strokes that leave the weave of the canvas quietly visible. The dress is scumbled and broken, allowing ground tones to glimmer through and suggest soft cloth. The balusters are modeled with brisk, calligraphic accents that imply volume without slick blending. The tiles are painted in assertive, crossing strokes that keep the foreground alive. The result is a surface that records decisions rather than erasing them, a present-tense skin that contributes to the work’s freshness.

Kinships within 1919

“Woman Holding Umbrella” belongs to a cluster of balcony and parasol compositions from the same year. Compared with versions where red dominates or where pattern saturates the room, this canvas is cooler, more tonal, closer to a study in blue and green. It shares with “Woman with a Green Parasol on a Balcony” the vertical pressure of door and jamb, but here the palette is quieter and the drawing more sketch-like, which intensifies the sense of daylight and air. Together these works map Matisse’s systematic testing of how few elements can secure a complete climate.

Palette and Likely Materials

A concise palette delivers the effect. Lead white supplies the body of light in door, dress, and sky. Ultramarine and cobalt blues define sea and cool shadows, sometimes tempered with black to reach slate. Viridian or a blue-leaning green commands the parasol, deepened with black and warmed with touches of yellow where light passes through fabric. Yellow ochre and raw sienna underpin the balustrade and parasol staff. Red lake or cadmium red light flickers in the tiled lattice and floral notes. Ivory black articulates contour, footwear, chair, and parasol ribs. The paint is mostly opaque, with translucent passages in the dress and sky to keep the atmosphere mobile.

The Ethics of Economy

The painting’s calm authority stems from economy. Matisse omits anything that would be redundant: no fussy perspective on balusters, no detailed facial modeling, no elaboration of wave or cloud. What remains are essentials placed exactly—planes, contours, temperatures. This economy is not stinginess but generosity to the viewer, who is invited to complete forms and to feel the balance that proportion and color produce. In the wake of wartime tumult, such clarity amounts to an aesthetic stance: steadiness, sufficiency, and light.

How to Look

Approach the canvas as you would the balcony it depicts. Stand near the lower edge and study the tiles until the red lattice begins to pulse. Step along the diagonal to the shoes; feel how their black anchors the figure. Rise through the cool field of the dress to the face; notice how few strokes carry its expression. Lift into the green umbrella and let its ribs echo in your eye. Drift out to the sea’s paired bands and back along the balustrade’s swelling forms. Repeat the loop. With each pass, the picture moves from depiction to rhythm, from scene to chord.

Meaning in a Modern Key

“Woman Holding Umbrella” offers a modern answer to an ancient genre. Instead of heroic narrative or anecdote, it proposes that painting’s subject can be the steady pleasure of placement—how color and line can hold a body in air. The picture’s world is modest: a chair, a balcony, a sliver of sea. Yet through exact relationships it achieves an abiding poise. That poise is the message: in a shallow designed space, light and shade, warm stone and cool sea, human rest and coastal air can be made to agree.

Conclusion

With door, rail, parasol, and sea, Matisse composes a complete climate of looking. The figure is less a personality than the pivotal tone in a carefully tuned chord. Everything is economical, nothing is brittle; the scene is calm without inertia. As so often in the Nice period, the result is a painting that seems simple at first and inexhaustible on return—a small balcony turned into a durable architecture of light.