Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

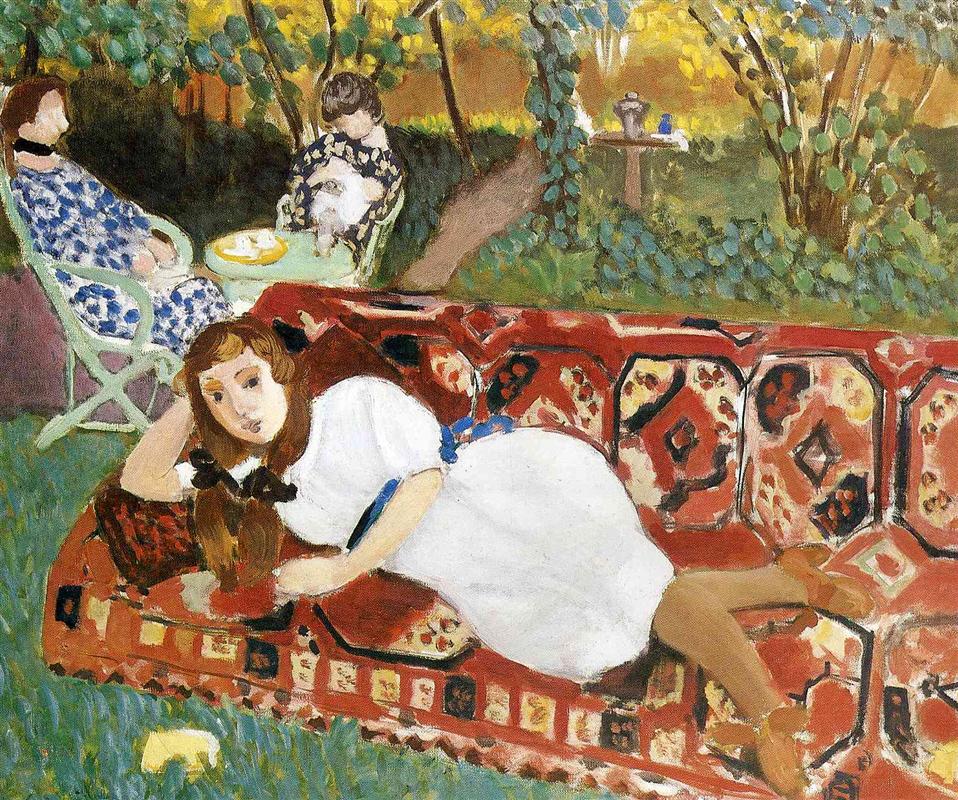

Henri Matisse’s “Young Women in the Garden” (1919) is a sun-warmed tableau of leisure that turns a domestic backyard into a stage for color, pattern, and rhythm. A reclining girl in a white dress occupies the foreground on a red oriental carpet or divan; behind her, two companions sit at a small tea table beneath foliage, one cradling a small white dog. The entire image—grass, shrubs, carpet, dresses, faces—has been simplified into lucid planes whose edges are stated with the frank, elastic contour that defines Matisse’s Nice period. Instead of telling a story through gesture, the painting builds a climate through color. It shows how a quiet afternoon can be arranged so that looking becomes a kind of breathing.

1919 in Nice: A New Grammar of Calm

The painting belongs to Matisse’s early Nice years, when he recentered modern painting around clarity rather than shock. After the disruptions of the war decade, he sought rooms and gardens where light was even and dependable and where pattern could serve as structure. In this grammar, carpets, dresses, trellises, and shutters are not décor; they are load-bearing elements that organize space. “Young Women in the Garden” is the outdoor counterpart to his interiors of 1919. The garden behaves like a room with green walls and a patterned floor, and the figures relax inside it the way sitters repose on divans and under parasols in his studio canvases.

First Look: A Reclining Foreground and a Conversing Background

At first glance, the eye goes straight to the reclining girl whose white dress glows against the heavy red of the carpet. She props her head on one arm, her long hair tied with dark bows, her body aligned with the diagonal of the divan. The carpet’s design—octagonal medallions in brick red, black, and rose—repeats like a drumbeat. Behind and above her, two women dressed in blue-patterned robes sit with a tea service on a yellow table. Further back, a birdbath or pedestal sits amid shrubs, catching the last gold of afternoon. The picture’s mood is unhurried and companionable. Even the small dog dozing in one woman’s lap contributes to the sense that nothing urgent must be done.

Composition: A Theater of Two Planes

Matisse divides the painting into two dominant planes: the red carpeted couch in the foreground and the green garden beyond. The couch runs like a diagonal stage across the bottom third; its front edge and patterned band operate as a visual rail, just as a balcony balustrade does in his window pictures. The garden plane is more vertical, filled with uprights of trunks and stems and the circular punctuation of shrubs and table. Between these planes a narrow seam of soil and shadow functions as a hinge. The reclining figure is the star of the lower stage; the seated pair, framed by shrubbery, are an answering chord in the upper stage. The composition is a conversation between red and green, horizontal ease and vertical shelter.

Pattern as Structure

The oriental carpet is not a prop; it is architecture. Its repeated medallions and border squares create a grid that stabilizes the foreground while amplifying the whiteness of the dress. The blue floral prints of the background dresses echo that logic on a smaller scale, creating a secondary patterned field around the tea table. Even the foliage joins this chorus: disks of leaf clusters and chains of creeping ivy read as ornamental modules that lock the space. Decoration, here, is the skeleton of the scene. It makes the garden legible as a designed place rather than an amorphous thicket.

Color Architecture and Temperature

The palette is a classical Nice chord: warm reds and ochres balanced by cool greens and blue-greens, with whites used not as absence but as active light. The carpet’s brick red is tempered with pinks and earthen tones so that it breathes rather than shouts. The garden greens range from cool mint to dark olive, each patch chosen to keep the space open. The two background dresses maintain a cool register that harmonizes with the vegetation while allowing the lemon of the tea table and the gold flickers in the distance to sparkle. The foreground girl’s white dress, tied with blue ribbons, is the high-key pivot that unites both climates. It is illuminated rather than shaded, yet its edges carry soft lilac and ochre temperatures that prevent chalkiness.

Light and Season

This is late-day Mediterranean light filtered through leaves—a climate rather than a spotlight. There is no hard cast shadow; volumes turn gently by temperature shifts. The distance glows yellow-green, suggesting sunlight falling through foliage onto a light lawn. The carpet’s reds are moderated by haze; the dresses’ blues remain fresh without chill. The small dog reads as a tuft of luminous white; the tea service on its yellow table seems to hold a private sun. Everything in the picture feels like early evening: the air cooling, the colors saturating, talk drifting.

Drawing and the Living Contour

Edges carry decisiveness without rigidity. Dark, slightly blue lines articulate the carpet’s border, the outline of limbs, the backs of chairs, and the edges of trees. Yet these lines swell and thin as they pass around forms; they never imprison color. The reclining girl’s face is drawn with brisk, exact marks—the dark curve of the eyelid, the brief stroke for nostril and mouth—enough to fix attention without demanding portrait psychology. Objects are freest where they can be understood in a stroke: the curve of the jug on the distant pedestal, a handle on a chair, the silhouette of a shrub. Matisse’s contour is not illustration; it is architecture that holds color to the surface while letting space remain breathable.

Space: Shallow, Habitable, Designed

Depth is built through overlaps and the stacking of planes rather than through perspective tricks. The red divan overlaps grass; the reclining figure overlaps the divan; the seated group overlaps shrubbery; the birdbath and yellow light overlap the furthest hedge. Because each layer is also a large colored shape, the painting stays a designed object even as it admits the sensation of stepping into a garden. You can feel where your feet would land if you approached: first on grass near the corner of the carpet, then at the couch’s base, then along the path between shrubs. The space is short but convincing, an intentional stage for the drama of color.

Rhythm and the Eye’s Path

The painting teaches you to look in loops. One natural path begins at the girl’s face, passes along her arm to the carpet pillow, then follows the medallions to the right and sweeps back across the border squares. From there you lift to the blue-clad woman at left, move to the central figure holding the dog, and then travel toward the sunlit birdbath. The foliage arcs return you to the girl’s head. On each pass, correspondences appear: the dog’s white echoes the dress; the tea’s yellow repeats the glints in the distance; the blue ribbons answer the printed robes; the red carpet finds a muted partner in the earthy trunk that slices up the middle. Rhythm replaces narrative; looking, not story, is what unfolds.

The Reclining Figure: Ease Without Odalisque

Matisse’s Nice interiors famously include odalisques. Here the reclining pose carries none of the erotic theater of those later works. The young woman’s demeanor is easy, her gaze casual, her body neither offered nor defended. The white dress, with its blue bows, emphasizes youth rather than seduction. By placing the figure outdoors and setting her among companions engaged in tea and talk, Matisse steers the motif toward domestic leisure rather than fantasy. Still, the pose allows him to orchestrate the diagonal of the divan and to test white against red at a scale that energizes the whole canvas.

The Seated Pair: A Secondary Chord

The two background women, in matching or rhyming blue garments, form a stabilizing dyad. They are presented in profile and three-quarter view, reducing psychological demands and emphasizing the shapes of their dresses. The small round table between them collects yellow light that tethers the dyad to the distant garden glints. Their presence folds hospitality into the scene: this is a place where friends sit, pour tea, and stroke a pet while another companion daydreams. The group reads as a single chord—blue-white-yellow—that answers the foreground chord of red-white-brown.

The Garden as Room

Branches arch overhead like a ceiling; the hedge forms a back wall; the red carpet lies like a floor. Matisse often transformed interior elements into landscape motifs and vice versa, and this painting continues that exchange. The birdbath or pedestal functions as a mantel or console would in a room; the tea table floats like a small round side table in a salon. Because the garden is built from patterned units—leaf clusters, branch rhythms—it operates as a decorated interior, yet the breathing of the greens and the gold light insist on open air. The painting becomes a halfway world between salon and grove.

Material Handling and Surface

The surface carries energy without fuss. The carpet is loaded with thicker paint that leaves ridges along medallion edges; the grass is laid in with shorter, springy strokes that mimic tufts; the foliage is dragged in loose swirls, allowing underpaint to sparkle through; the dresses are thinly painted so that the patterns read in a breath. This variety prevents monotony in a composition dominated by large, repeated shapes. It also gives the eye the tactile information it craves: you can feel the nap of the carpet, the crispness of cotton, the soft fur of the lap dog, the cool stone of the birdbath.

Palette and Likely Pigments

A concise set of pigments suffices for the effect. Brick reds and siennas build the carpet, sweetened with cadmium red light and moderated by earthy browns. The many greens range from viridian cut with yellow for fresh leaves to olive mixes with ochre for shaded hedges; grass likely relies on chromium oxide tinted with yellow and white. The blues in the dresses include ultramarine with white and a hint of black, while their floral whites contain a trace of cool blue to keep them from competing with the girl’s bright dress. Skin rests on ochre-white mixtures with light rose accents. Black is spared for contouring and deep carpet motifs. The harmony is temperature-driven rather than hue-noisy.

Kinship with “Tea in the Garden” and Other Nice Works

“Tea in the Garden,” painted the same year, presents a broader, more symmetrical garden tea party, with chairs and samovar arranged in a semicircle under trees. “Young Women in the Garden” narrows the field and intensifies the play between a single patterned plane and the living green. It also speaks to “Woman on a Couch” and “Reclining Nude on a Pink Couch,” which develop the diagonal divan indoors. Across these works, Matisse tests how a reclining figure can anchor composition, and how pattern can behave as architecture, whether the scene is a studio or a backyard.

Presence Without Gossip

There is no anecdote to decipher—no letter being read, no dramatic exchange, no gesture demanding tale-making. The painting’s meaning emerges from how it feels to look: a balance of warmth and cool, of rest and chatter, of red gravity and green air. That refusal of narrative is not evasive; it is generous. It gives viewers room to inhabit the afternoon without being conscripted into a script. The painting’s subject, finally, is the condition Matisse pursued in Nice: a durable happiness constructed from proportion and color.

How to Look: A Practical Walkthrough

Stand close to the lower edge and study the carpet medallions. Notice how little modeling they require to produce a sense of depth and pile. Move to the girl’s dress and watch how white turns with a touch of lilac or ochre where it meets shadow. Step back until the blue prints of the background dresses merge with the foliage; the women begin to read as cool flowers amid green. Let your eye hop to the small dog and then to the tea table; feel the yellow pull you toward the bright glade at the far right. Return along the arc of shrubs to the girl’s gaze. Repeat the loop. Each circuit loosens the desire for storyline and sharpens the pleasure of placement.

Why It Endures

“Young Women in the Garden” is a persuasive answer to a modern question: how can painting offer consolation and clarity without sentimentality? Matisse’s reply is to orchestrate a few large planes, let pattern do the scaffolding, and tune color so that warm and cool breathe together. The result is a summer afternoon you can keep returning to, not for gossip about who these women were, but for the felt permission the picture grants—to rest, to look, to let red and green converse until they settle into harmony.