Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

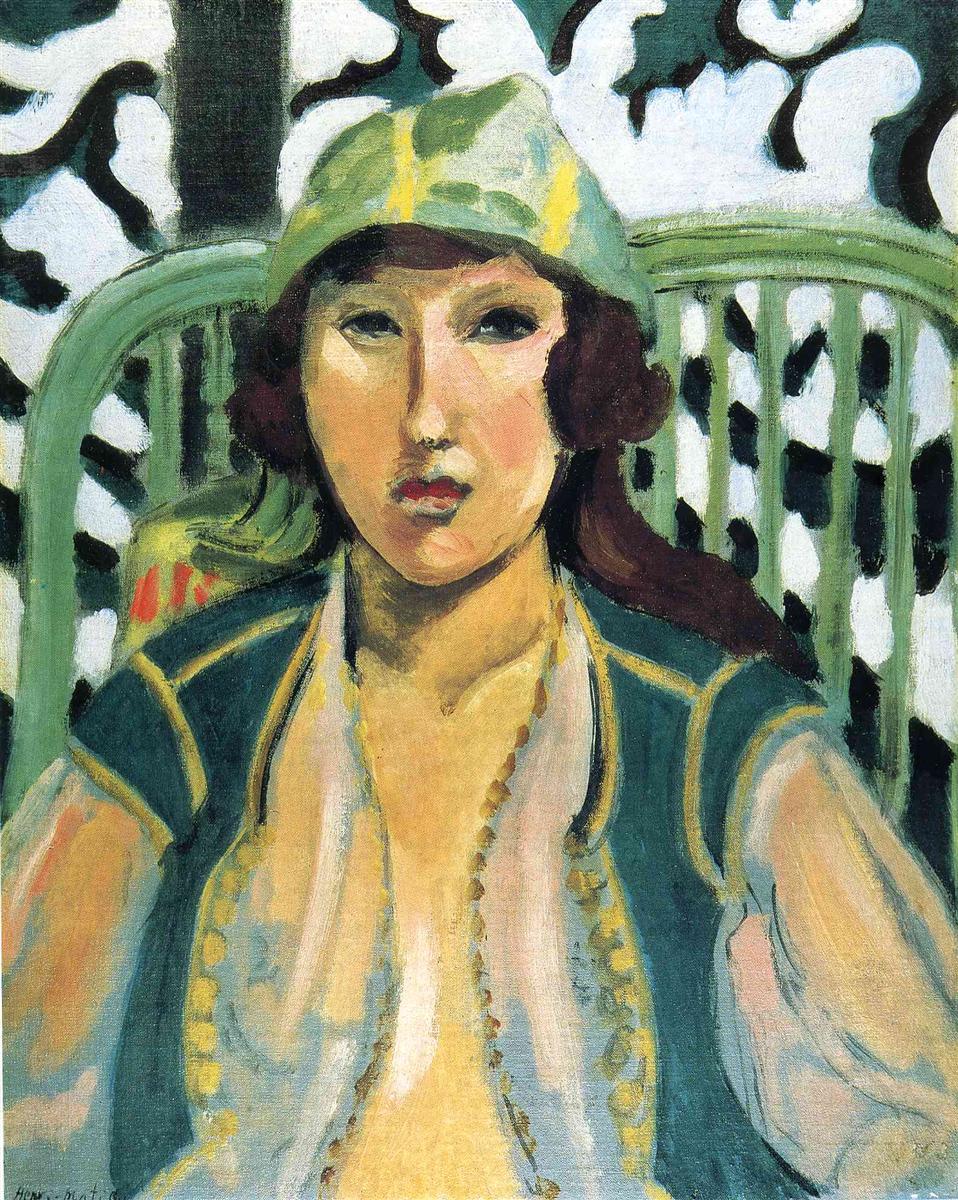

Henri Matisse’s “Woman with Oriental Dress” (1919) condenses the artist’s Nice-period discoveries into a portrait that is both intimate and declarative. A young woman, cropped tightly at the shoulders, faces us in a half-length pose. She wears a small cap and a sleeveless, embroidered vest over a pale chemise that opens along the chest. Behind her, a filigreed screen and the curved bars of a chair generate a patterned halo that keeps the figure firmly on the surface while suggesting a shallow, breathable space. The palette is a cool orchestra of blue-greens, creams, and olive notes, punctuated by warm touches in skin and lips. With very few elements, Matisse stages a conversation between ornament and flesh, line and color, presence and design.

The Nice Period Setting

Painted in 1919, this canvas belongs to the first phase of Matisse’s Nice years, when he pivoted from the explosive experiments of earlier decades to a new ideal of calm clarity. In Nice, he cultivated interiors where light was soft and constant, surfaces were patterned but legible, and forms were simplified into large, harmonious planes. Garments inspired by North Africa and the eastern Mediterranean—vests, sashes, caps, and caftans—entered the studio not to produce ethnographic narratives but to supply the painterly materials he prized: broad areas of color, rhythmic borders, and tactile edges that could be stated with a single stroke. “Woman with Oriental Dress” exemplifies this program. The costume is a tool of composition, and the room’s decoration is structural, not descriptive luxury.

First Look: A Portrait Built from Planes

At first glance, the painting reads as three stacked registers. The head and cap rule the top third, a compact oval set beneath a sliver of patterned screen. The torso and vest occupy the middle, where the deep teal of the garment meets the warm tones of the skin. The forearms and chemise, modeled with pale greys and peaches, finish the lower band. Each register is held together by a strong contour—the living line that Matisse thickens or thins to keep forms breathing. The cropping is close, almost cinematic, so that our attention stays on the structure of face, garment, and ground rather than drifting into a wider setting.

Composition and Framing Devices

Matisse composes with a handful of decisive arcs and uprights. The rounded top of the chair backs the sitter like a stage proscenium, its green bars repeating as a cadence behind shoulders and cap. The black-and-white screen at the very top behaves like lacework, a frieze of abstract leaf forms that crowns the image without stealing focus. The vest delivers two long diagonals that converge toward the open neckline, bringing the eye to the center and then releasing it outward along the embroidered edge. The symmetry is real but flexible; tiny asymmetries—the cap’s tilt, the shoulder angles, the vest’s imperfect mirror—keep the picture alive.

Color Architecture and Temperature

Three color families carry the painting. Cool blue-greens shape the chair and vest, establishing the dominant climate. Warm ochres and rose tones define the skin, lips, and bits of embroidery, giving human heat to the cool room. Neutral whites and soft greys model the chemise and background, allowing transitions without drama. Matisse distributes these families with care. The cools concentrate along the edges—the cap, the vest panels, the chair—forming a frame that cradles the warmer center of the face and chest. Small yellowy knots along the vest’s edge sprinkle warmth back into the cool field so the garment never goes flat. This interleaving gives the portrait its serene but vibrant pulse.

Light: A Mediterranean Evenness

The light in “Woman with Oriental Dress” is characteristically Nice—steady, high, and humane. There is no harsh shadow or spotlight theatrics. The face turns with gentle temperature shifts rather than deep value jumps. Cheeks carry a hint of peach, forehead slips into a cooler ivory, and the nose is set with two or three strokes that suggest structure without insisting on anatomy. The chemise is modeled with the quietest grey touches so that the open neckline reads as air and fabric rather than as drama. This evenness allows the color to bear expressive work while preserving a sense of physical presence.

The Costume as Pictorial Device

Matisse’s “oriental” costume is a studio invention—an ensemble chosen for its painterly utility rather than for ethnographic specificity. The vest supplies large fields of saturated color bordered by narrow, beaded seams, perfect for testing the relationship between plane and decorative edge. The cap crowns the head with a soft dome of green that echoes the chair’s arc, creating a self-contained figure against the patterned ground. The chemise’s opening offers a vertical of warm flesh that meets the vest’s cool diagonals, producing a clear, legible knot at the center of the canvas. Costume here is not character; it is architecture.

Pattern and Ground

Behind the sitter, Matisse stages a duet between two kinds of pattern. The uppermost band shows abstract leaf-like forms in black against white, painted broadly enough to read as both decoration and flat silhouette. Below, the vertical slats of the chair run in a regular rhythm. Together they create alternating beats—organic-whorl, mechanical-bar—that stabilize the surface and keep the head from floating. They also echo and amplify the internal rhythms of the vest and braiding. This is a hallmark of the Nice grammar: pattern is not depicted for its own sake; it is recruited to hold the space and choreograph the viewer’s eye.

Drawing: The Living Contour

Contour in this portrait is a thinking instrument. Thick black lines firm up the vest’s outer edges and the chair’s sweep; fine, elastic strokes draw eyelids, nose, and mouth; the cap’s outline softens where it meets hair and hardens where it meets background. Matisse’s line is never timid, but it is never mechanical either. It swells where mass turns away, thins where light catches, and occasionally breaks so that color can complete the shape. This approach preserves the flatness of the painting while letting forms feel tactile and present.

Brushwork and Surface

The paint handling is frank. You can see the single strokes that set the cap’s highlights and the soft scumbles that blur the chemise’s folds. The skin is laid in with broad, semi-opaque patches that remain open at the edges, allowing underlying tones to glimmer through. The vest’s greens show slight variations—cooler near the armholes, warmer in the central panels—so that the garment feels lived-in rather than poster-like. There is no varnished finish to mask the process. The surface is a record of decisions, which is why the portrait feels present-tense, as if the sitter had just raised her eyes to meet ours.

Face and Expression

Matisse resists the lure of portrait psychology delivered through detail. The mouth is small but decisive, the eyes simplified to dark lids and bright whites, and the nose is built from two brisk strokes. Yet the sitter’s presence is unmistakable. The quiet compression in the lips, the level glance, and the alignment of head and shoulders produce a mood of composed attention. Instead of extracting biography from features, the painting gives you a climate of character: self-possessed, unhurried, available to the light.

Space: Shallow, Habitable, Designed

Depth here is short and controlled. The sitter presses close to the plane, but the chair’s arc and the screen’s filigree open a sliver of breathable room around her head. Overlaps—not vanishing points—do the spatial work: cap over hair, hair over vest, vest overlapping arms, chair behind all. This designed shallowness keeps the painting an object rather than a window while still admitting the sensation of proximity. You could lean in and whisper to the sitter; you could also step back and read the portrait as a flat arrangement of colored shapes. Matisse wants both experiences available at once.

Rhythm and the Eye’s Path

The portrait conducts the gaze in a repeatable loop. Most viewers start at the face, then follow the beaded seam down the open vest to the chemise’s center, cross to the opposite seam, rise along the shoulder to the cap, glide across the chair’s arch, and return to the eyes. Each lap reveals new rhymes: the yellow beads answering the lip’s warmth, the cap’s green echoing the vest, the black screen motifs whispering to the black drawing of hair and features. Rhythm replaces anecdote; the act of looking becomes the painting’s subject.

Comparison within 1919

“Woman with Oriental Dress” converses with several portraits Matisse made the same year. It shares with “The Black Table” the use of a deep, cool plane to hold warm flesh, and with “The Green Sash” the strategy of a central vertical that cinches the figure. Compared with the more expansive “Woman with a Green Parasol on a Balcony,” this canvas is tighter and more frontal, emphasizing contour over vista. Across them all runs the Nice vocabulary: large planes, patterned supports, calm light, and color that persuades by placement rather than by intensity alone.

Palette and Likely Materials

The economy of color suggests a concise palette deployed opaquely. Lead white provides the base for chemise and highlights. Ultramarine, Prussian blue, and a touch of yellow ochre build the blue-green of chair and vest. The cap’s lighter greens are likely the same family cut with additional white and a breath of Naples yellow. The skin sits on mixtures of white, ochre, and a warm earth with touches of alizarin or vermilion for lips and cheek notes. Ivory black is used sparingly but decisively for contours, hair accents, and screen motifs. Paint is mostly opaque, with translucent scumbles reserved for the soft modeling of fabric and flesh.

The Question of “Orientalism”

The title names the garment rather than the sitter, and that matters. Matisse’s interest is not an ethnographic claim but a painterly one. He treats “Oriental” textiles and cuts as available vocabularies of color and edge that expand Western studio habits. In this painting, the vest’s beaded edge and the cap’s supple dome provide opportunities for arabesque and plane; they do not anchor a story about place. What could lapse into costume becomes, in his hands, a syntax for clarity and repose. The sitter remains a person, not a type.

How to Look, Practically

Stand close enough to see the brushwidths in the cap and the seams of the vest. Notice how the eyes are built from a few assertive lines, not from gradients. Step back until the beads along the vest’s edge fuse into a single warm fringe. Shift left and right to feel the chair’s curve gathering the head. Then return to the mouth and register how its small, warm compression holds the entire color chord together. The picture becomes most persuasive when you alternate between reading it as surface design and as a living presence; Matisse provides for both.

Emotional Climate and Lasting Appeal

The portrait’s emotion arises from composure. The sitter seems fully at ease inside a room made of patterns, her flesh held by cool color yet never chilled by it. For viewers, that balance produces a quiet exhilaration: the recognition that a few well-placed shapes and temperatures can make a person feel vividly present. This is the Nice lesson, and it is why paintings like this still look new. They do not need narrative elaboration or technical fireworks. They achieve more by choosing less and placing everything exactly.

Conclusion

“Woman with Oriental Dress” is a compact statement of Matisse’s 1919 ideals. A figure is frontally presented, framed by decorative structure, bathed in humane light, and described with line that remains alive. Costume supplies architecture; pattern becomes space; color carries mood. The sitter’s identity is not dissolved by reduction; it is clarified by it. What remains, after the eye has looped again and again through cap, eyes, beads, and chair, is a feeling of poised attention—the very quality Matisse sought to give to painting itself in the years after the war.