Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

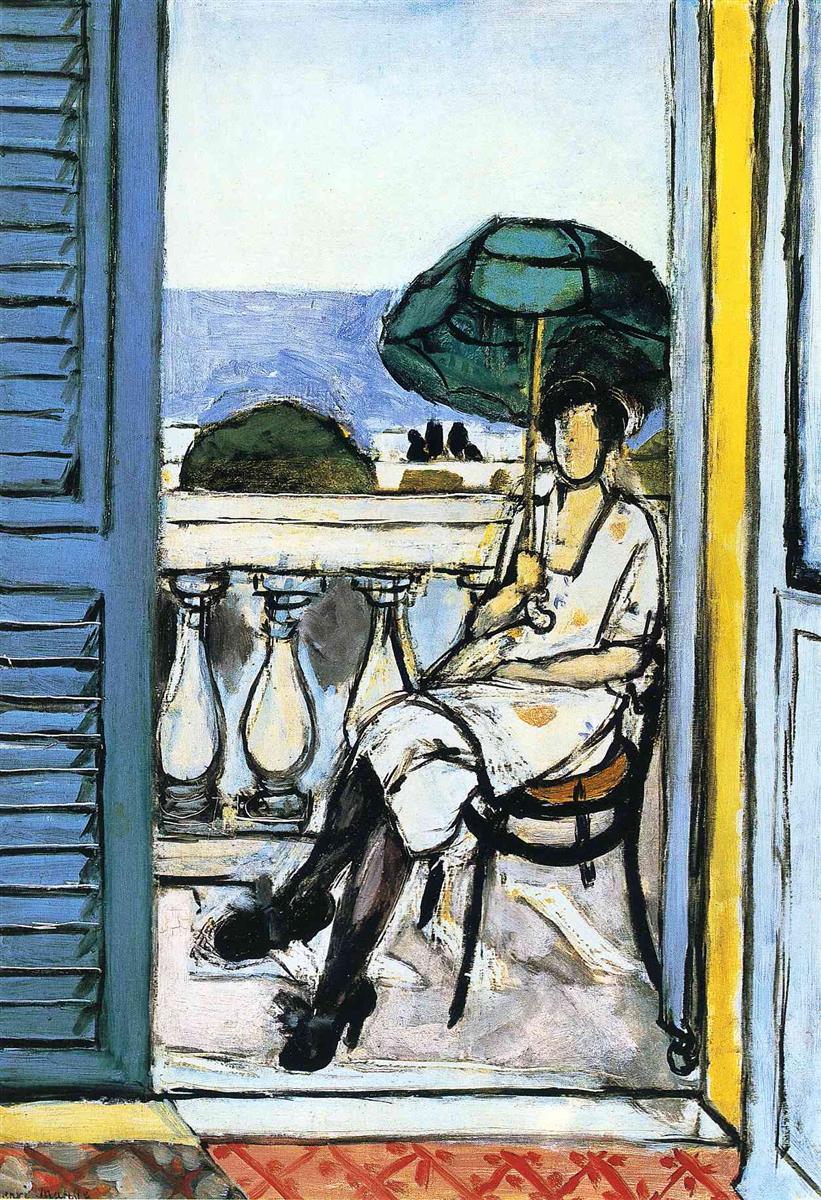

Henri Matisse’s “Woman with a Green Parasol on a Balcony” (1919) distills the Nice period into a single, lucid chord: sea light, a shallow interior threshold, and a figure whose presence is defined by placement and color more than by descriptive detail. The sitter occupies the balcony like a punctuation mark in the rhythm of shutters, balustrade, and sky. A deep teal parasol crowns her, the Mediterranean unfolds behind her in a pale banded horizon, and the doorway’s blue and yellow uprights press the scene into a compact stage. With a few large planes and a handful of incisive contours, Matisse transforms a casual seaside interval into a complete architecture of attention.

The Nice Period Context

Painted during Matisse’s first postwar seasons in Nice, the picture belongs to a body of work that reimagines modern painting around clarity and calm. Instead of the incendiary color of Fauvism or the jangling fragmentation of Cubism, Matisse builds spaces that are shallow yet habitable and uses decoration as structure rather than embellishment. Balconies, shutters, mirrors, and parasols are not props so much as tools for measuring light. In 1919 he was exploring how little a painter needs to make a room feel open to air and time. This balcony scene shows the method at full strength: few colors, broad planes, and line that is frank, elastic, and decisive.

First Impressions and Motif

The canvas reads at once as a set of interlocking rectangles and curves. At left, a blue shutter consumes a vertical band; at right, a yellow doorjamb and a sliver of blue frame press inward. Between them opens a white balcony whose balusters are modeled as bulbous, transparent drops. Beyond sits the sea, a low middle band that oscillates between indigo and pale azure under a high, nearly white sky. The woman, seated in three-quarter profile, wears a light dress with black stockings and dark shoes; her face is simplified almost to anonymity. She holds a green parasol that arcs over her head like a leafy canopy. The floor tiles at the threshold crackle with reddish lattice, recalling the patterned stages he used elsewhere in Nice. The effect is not anecdote but chord: a crisp play of architectural planes, marine light, and a figure defined by silhouette and temperature.

The Balcony as Modern Proscenium

Balconies fascinated Matisse because they compress exterior and interior into a single plane. Here the doorway and shutter act like curtains, converting the balustrade into a proscenium rail. The figure becomes a performer of stillness on a small stage open to the sea. That theatrical metaphor matters because it organizes the viewer’s behavior. We stand just inside the room, looking out; the jamb and shutter keep us from falling into the distance. The painting thus preserves flatness while allowing the pleasure of a view, a hallmark of the Nice language.

Composition: A System of Frames and Ovals

The composition turns on two frames and two ovals. The frames are the vertical bands of shutter and door that press the image inward. They stabilize the scene and deliver a measured chromatic contrast—blue at left, yellow at right—whose echo returns in sea and stone. The first oval is the parasol, a dense green disc whose facets are picked out with black. The second is implied by the curve of balusters, the arc of the chair, and the rounding of the woman’s crossed knees. These ovals soften the strict geometry of the frames and introduce bodily rhythm into architectural order.

Color Architecture and Temperature

Matisse limits himself to three dominant families. Cool blues and blue-greens make up the shutter, sea, and shaded whites; warm yellows and ochres occupy the jamb and sunlit stone; deep blacks and near-blacks articulate contour, footwear, hair, and the parasol’s structure. The woman’s dress is a fragile, chalky off-white touched with hints of peach and lilac that keep it breathing in the glare. Because each color family recurs across different substances—blue as wood and water, yellow as wall and light, black as line and cloth—the eye reads coherence rather than collage. The green parasol, hovering between blue and yellow, is the hinge that fuses the climate.

Light: Measured Mediterranean

The light is Riviera noon moderated by architecture. Sun strikes the jamb to the right and the balcony stone; everything else is bathed in a cooler, diffused brightness. Matisse avoids layered shadow modeling. Instead he turns forms with temperature. The balusters swell by drifting from cold gray-blue to milky white, the woman’s dress turns at edges by slipping toward lilac, and the sea shifts from deep bands near the horizon to paler water under the sky. This measured light lets the black drawing stay legible and grants the parasol’s green its soft, vegetal glow.

Drawing and the Ethics of Economy

Contour carries the image. Thick-and-thin black lines, sometimes broken, sometimes pressed, state the essentials: the loop of the chair seat, the curve of the ankle, the scallop of the baluster necks, the ribs of the parasol. These are not ornamental outlines; they are structural, living edges that keep things held together on a flat plane. The face is sketched with a few ovals and arcs, just enough to register attention without pinning down identity. By refusing detailed description, Matisse protects the picture’s graphic logic and leaves atmosphere to color.

The Parasol as Pictorial Device

In the Nice interiors, parasols are never mere accessories. They supply a large, mobile color field that shades the head and connects figure to climate. Here the green disc performs multiple jobs. It crowns the figure, compressing the vertical space between balustrade and sky. It offers a cool counterweight to the warm jamb, preventing the right margin from overwhelming the figure. And its internal ribs echo the shutter slats, binding object and architecture. The parasol’s staff, a vertical ochre, is a miniature of the doorjamb beside it—a sly rhyme that stabilizes the right half.

The Balustrade as Transparent Architecture

Matisse paints the balusters as blown-glass forms, their interiors filled with grays and reflected blues. This is not a literal description of stone; it is a way to keep the middle ground porous so that air moves through the architecture. The swelling shapes also play against the straight shutter slats, giving the composition a syncopation of verticals—rigid louver, fluid baluster, rigid jamb—that keeps the balcony alive as a bridge between room and sea.

Threshold Pattern and the Memory of Red

At the bottom edge, a narrow strip of floor tiles erupts in a red lattice. This small, warm plane carries a memory of Matisse’s famous red floors from other Nice interiors and provides a tiny but potent counterpoint to the cool sea. It also locates us physically: our toes, as viewers, feel poised on that patterned threshold. From there the space opens outward in a sequence of measured steps, never letting us lose contact with the surface.

Space: Shallow, Convincing, Designed

Depth is short and controlled. The figure sits only a pace or two beyond the doorway, the balustrade just behind her, shrubs and sea beyond in simplified bands. Overlap—not perspective—is the engine: parasol before sea, figure before balusters, shutter before balcony. This designed shallowness allows each plane to remain a colored shape on the canvas while still implying a world we could enter. You sense breeze and brightness without becoming a tourist in an illusionistic vista.

Rhythm and the Viewer’s Path

The eye makes a repeatable loop. It often begins with the parasol’s green, drops to the woman’s crossed knees and dark shoes, skims left across the row of glassy balusters, climbs the shutter’s slats to the pale sky, and then returns down the warm jamb to the figure’s shoulder and back to the parasol. Each lap confirms symmetries and rhymes: green disc to blue sea, black contour to shutter divisions, yellow jamb to ochre parasol staff, red threshold to warm stone. The painting teaches looking as a bodily rhythm—balanced, unhurried, and breathable.

Presence without Anecdote

Matisse offers no narrative beyond the fact of sitting with a parasol on a bright day. The face is deliberately generalized; emotion resides in placement, posture, and climate. Crossed legs and the parasol’s tilt express a relaxed vigilance—the body is at ease, the hand holds shade against glare. The anonymity is not indifference but an invitation to attend the whole configuration rather than treat the sitter as a character in a story. The picture’s feeling arises from the way color fields keep companionship under sun.

Kinships within 1919

The canvas speaks directly to other balcony and window pictures from the year. It shares with “Woman with a Red Umbrella” the device of a colored disc held against the sea, but here the palette is cooled and the drawing more spare. It echoes “Woman by the Window” in the balance of interior frame and exterior blue, yet pushes the figure further outdoors. The red lattice at the threshold recalls the stage-like floors in “Interior with a Violin Case,” while the glassy balusters anticipate later Nice interiors where decoration becomes space. Across these works, Matisse refines a grammar in which a few planes and a handful of temperatures make an entire climate.

Materials and Likely Palette

A succinct palette powers the picture. Lead white and a cool gray mix build walls, balusters, and sky. Ultramarine and cobalt blues serve the sea and shutter, shifting warmer or cooler by admixture. Viridian or a blue-leaning green constructs the parasol, deepened with black and pricked with darker ribs. Yellow ochre and Naples variants warm the jamb and parasol staff. Ivory black articulates contour and footwear, its thickness varied to keep edges alive. Paint is largely opaque, with scumbles on stone and sky and more loaded strokes in shutter and parasol. The surface remains legible, every decision visible, which is central to the painting’s present-tense vitality.

How to Look

Stand close first. Count the strokes that form a baluster, the few dark passes that make a shoe sit on light slab, the ribbing in the parasol that turns a flat green into a shade-bearing object. Step back and watch the blue shutter lock the left edge while the yellow jamb warms the right. Let your eye travel the loop from parasol to knees to balustrade to shutter to sky and home again. Finally, notice how the facelessness of the sitter releases your attention to the orchestration of planes and temperatures. The painting’s subject becomes your own sustained looking inside a gentle climate.

Meaning in a Modern Key

“Woman with a Green Parasol on a Balcony” proposes a modern kind of portraiture: not biography or social role, but the felt experience of occupying a place. It is about shade against glare, stillness against breeze, human scale against architecture, interior against horizon. In a year of rebuilding after the war, the picture’s steadiness is not trivial; it is an ethic. Harmony is achieved not by sweetness but by exactness—of frame, contour, and color. That ethic would anchor Matisse’s work through the 1920s and remain a touchstone for painters seeking clarity without austerity.

Conclusion

With an economy that verges on audacity, Matisse makes a world from a shutter, a jamb, a balustrade, a band of sea, and a seated figure crowned by a green disc of shade. The composition is tight but never tense; the light is generous but never blinding; the drawing is frank but never rigid. Everything is placed, nothing is fussed. The result is a painting that feels both exact and relaxed, a balcony held open to air and time. It is a lesson in how color-built structure can turn a brief seaside pause into enduring poise.