Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

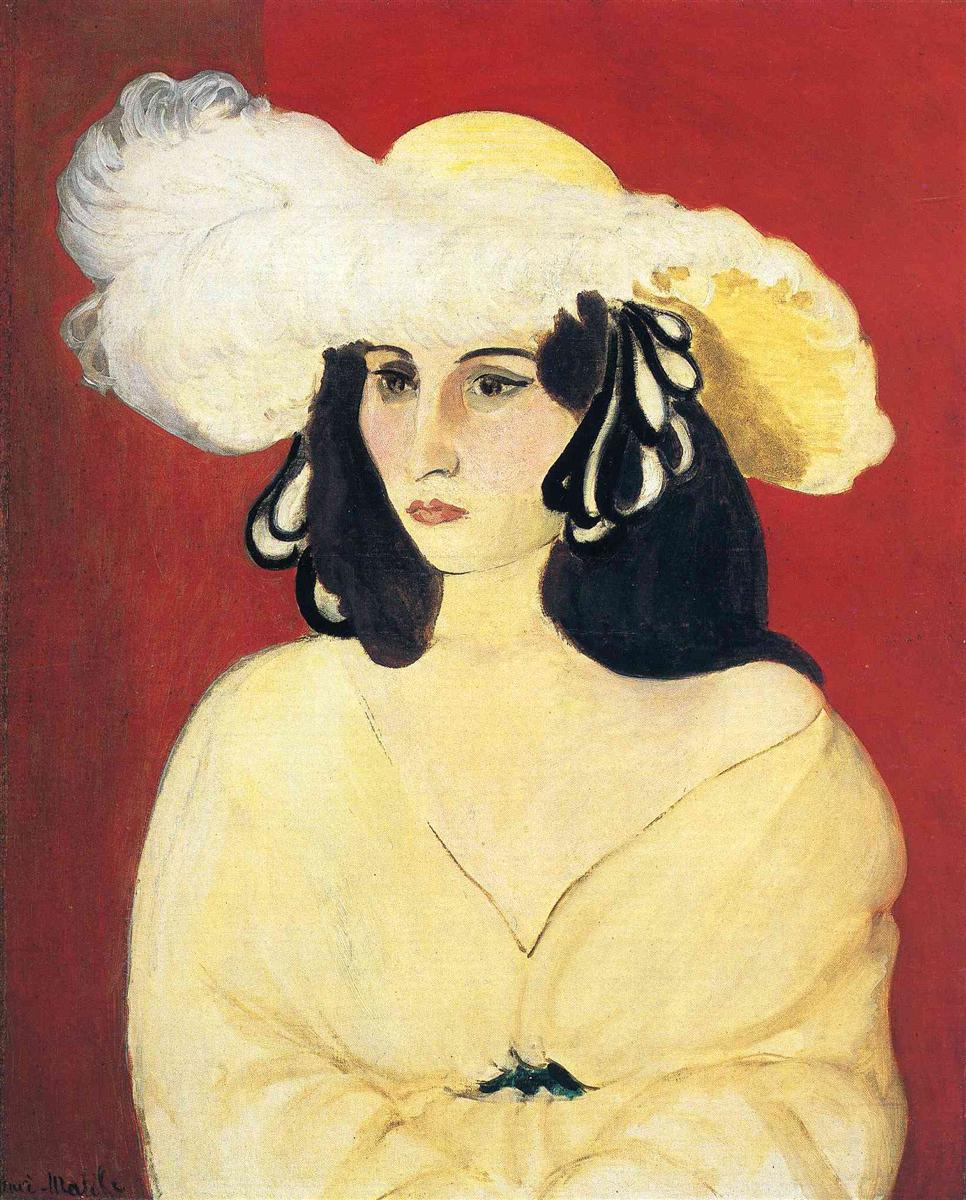

Henri Matisse’s “The White Feather” (1919) is a commanding portrait from the artist’s early Nice period in which a single figure, a monumental hat, and a flat red field become an architecture of color and poise. The sitter faces slightly to the left, her expression measured rather than theatrical. A vast hat—straw crown, extravagant white plume—spans the canvas like a cloud. Her ivory dress is rendered with extreme economy, more plane than fabric, its neckline and shoulder line established by the lightest of contours. Behind her, an unwavering scarlet ground eliminates anecdote and turns the figure into a decisive chord of warm and cool, soft and crisp, stillness and latent movement. With very few means, Matisse builds a portrait that feels timeless and unmistakably modern.

A Nice-Period Pivot

In 1919 Matisse was consolidating a new pictorial ethic after the turbulence of the previous decade. In Nice he cultivated calm interiors, steady light, and shallow, designed spaces. Decoration became structure; color carried mood and meaning. “The White Feather” belongs to this program, but it also previews the odalisque and studio portraits that would dominate the early 1920s. Its sumptuous hat and simplified gown hint at costume drama, yet the painting remains sober and architectural. Matisse uses adornment not to narrate a social role but to engineer relationships of color, edge, and surface—his true subject.

First Impressions

The first encounter is chromatic: the red ground is uninterrupted, its saturation pushing the creamy figure forward. Second is the scale of the hat—its pale straw crown and voluminous plume spread across the upper third like a secondary sky. Then the face resolves: dark hair framing a pale forehead, fine brows, eyes rendered with a few calligraphic strokes, lips held in a quiet line. The dress drops away into a single pale field whose edges barely exist. Nothing diverts attention from the essential encounter between face, plume, and red.

Composition as Figure–Ground Drama

Matisse organizes the canvas as a clear figure–ground problem and then solves it with a handful of shapes. The head-and-hat complex is a near-oval, broader than the shoulders, stabilized by the horizontal sweep of the feather. The torso forms a tall triangle whose base is the lower edge of the canvas. The red field is a single rectangle that he breaks only once—with a cool, vertical band on the left that slightly modulates the hue, like a wall in half-shadow. This subtle partition keeps the red from feeling poster-flat while preserving its structural authority. The portrait’s balance depends on these large shapes; smaller marks—eyelids, nostrils, a fold—are accents, not architecture.

Color Architecture and Temperature

Three families of color carry the painting. The first is the red ground, warm and saturated, acting as a stage and a foil. The second is the pale, creamy family that defines face, skin, hat crown, feather, and dress—cooler than the red, sometimes warmed toward straw or cooled toward ivory. The third is the deep, blue-black of the sitter’s hair and the feather’s black accents, which provide necessary gravity and draw the eye to the face. Because each family repeats across multiple forms—cream in skin and feather, black in hair and plume filigree—the composition locks together. The small rose tone of the lips and inner eye corners is the only high chromatic accent within the figure; its restraint amplifies its effect.

The Hat and the Feather

The hat is both object and metaphor. As object, it gives scale, framing the face and providing a bright, curving counterpart to the rectilinear ground. As metaphor, it behaves like a cloud: a soft, moving mass that carries light and breath. Matisse paints the plume not with fussy feather-by-feather description but with long, lightly loaded strokes that arc and dissolve. The plume’s opacity shifts, thicker near the crown, airier at the edges, so that daylight seems embedded in the paint. Black ribbon or feather details sit under the brim in bold teardrop shapes, echoing the hair’s darkness and preventing the hat from floating away. The hat is theatrical, but the handling is disciplined; it belongs to the logic of the painting, not to costume history.

Drawing: The Living Contour

Matisse’s drawing is frank and economical. The line around the neckline is a mere suggestion, enough to declare openness without laboring drapery. The jaw is drawn with a firm curve that softens near the chin; the nose is a small, exact structure of a couple of strokes; the eyelids are set with a measured thickness that makes the gaze calm rather than hard. Most daring is the nearly contourless body: the dress is a continuous field whose shape is given more by the red’s encroachment than by internal modeling. This strategy keeps the painting close to the plane and prevents volume from overpowering color relations.

Light and the Mediterranean Climate

The Nice light in this portrait is not dramatic; it is even and clarifying. There are no theatrical shadows cast across the face or dress. Volume turns with small temperature shifts—cooler under the eyes and along the jaw, warmer on the cheeks and crown of the nose. The feather possesses its own light, built from mixtures of white, pale yellows, and faint grays, a sunlit whiteness rather than studio glare. This climate allows the red ground to remain strong without throwing the skin into chalk or the feather into glare. The painting holds an interior serenity that feels like late morning in a quiet room.

The Psychology of Poise

Much has been written about Matisse’s portraits as images of serenity. Here poise is enacted rather than depicted. The sitter’s gaze is directed just past the viewer; the mouth is closed, neither tense nor smiling. The mass of the hat anchors her; the near-absence of dress detail prevents fidgeting. The red field, which might be read as passion in another painter’s hands, becomes here a contained warmth that the sitter tempers. She is not an odalisque or a society mask; she is a chord—face, hair, feather—tuned to a red ground. The effect is dignity without rhetoric.

Background as Active Plane

The background is not neutral. Its red is a protagonist with two crucial jobs: pushing the figure forward and flattening the ground so that design, not depth, governs the portrait. Matisse does allow a band of cooler red along the left edge, likely to prevent the field from feeling taut as a poster and to establish a lateral rhythm that echoes the feather’s arc. The field’s consistency makes small color differences in the figure more legible. In that sense, the red is an instrument panel on which the painting plays.

Hair, Black Accents, and Pictorial Gravity

The deep blacks of the hair and the feather’s under-brim marks are not merely descriptive. They supply gravity to a composition that otherwise might float away in creams and reds. The hair’s shape also frames the face with two large commas that echo the hat brim’s curve. Matisse thickens and thins these darks to keep the contour alive; where hair meets cheek, the line softens, while at the outer edges it hardens and darkens, anchoring the head against the ground. The small black bow or notch at the dress’s center subtly repeats this gravity low in the picture, tying upper and lower halves.

Material Handling and Surface

The paint surface exhibits Matisse’s Nice-period duality: opacities laid decisively and scumbles that let the canvas breathe. The red ground reads as relatively even but shows slight variations that keep it living. The feather’s whites reveal the brush; the dress’s field is smoother, with faint, almost erased lines suggesting seams. Thick–thin orchestration is everywhere—important in a painting that depends on very few forms. The result is a surface that feels present-tense, as if the painter’s decisions are still audible.

Space: Shallow Yet Habitable

There is almost no depth between sitter and ground, and that is the point. Matisse keeps the space shallow so that color and contour can bear expressive load. Yet the painting remains habitable: the hat projects enough to declare a world in front of the red; the head turns sufficiently to create a slight rotation in space; the dress’s triangular base implies the breadth of the torso. In place of measured perspective we get proportion, placement, and temperature—Matisse’s favored tools.

Echoes and Kinships in 1919

“The White Feather” belongs beside other portraits and interiors of the year. It shares with “The Green Sash” the reliance on a steady field and a single chromatic chord to establish presence; with “The Black Table,” the use of matte darks to stabilize bright planes; with “Woman with a Red Umbrella,” the readiness to let bold color fields carry mood. What distinguishes this painting is its near-monochrome discipline: red plus creams plus blacks, handled so that variety emerges within restraint.

Possible Sources and the Question of Costume

The sitter’s hat feels both contemporary and theatrical. In the Nice studios Matisse stocked shawls, hats, and textiles to vary form and color without chasing narrative. The plume’s extravagant mass is perfect for his purposes: a large, pale, malleable shape that can be modeled without fuss and that yields a rich contrast against red. Its period connotations—fashionable elegance, a whiff of performance—are less important than its pictorial function. The costume serves the painting, not the other way around.

Likely Palette and Technical Choices

A concise palette is sufficient for the effect: vermilion or cadmium red for the ground, moderated by a touch of earth to avoid harshness; lead white for feather, skin, and dress mixed with Naples yellow for straw warmth and with a little blue or black for cool shadows; ivory black and possibly a trace of ultramarine for hair and plume accents; a small amount of alizarin or vermilion for lips and inner eyelids. Paint is mostly opaque, with thin underlayers in the ground and feathery scumbles at the hat’s edge. Edges are controlled rather than blended; transitions in the face are achieved by temperature shifts more than by value jumps.

How to Look

Let the canvas settle first as three shapes—the red field, the pale hat-body mass, and the black hair accents. Then approach the feather’s edge and count the number of strokes it takes to suggest an entire plume. Study how the darkest hair touches the red at a few anchor points to pin the head to the plane. Step back and allow the face’s small rose notes to emerge against the large cream field. Notice how the left vertical modulation of red keeps the background alive. Repeat this look-close, step-back rhythm until the portrait’s calm begins to feel like a physical atmosphere.

Meaning Without Story

Matisse offers no biography for the sitter and no anecdotal cues. The painting’s meaning arises from what it makes you feel—composure, warmth held in check, the pleasure of well-placed color, the beauty of restraint. The white feather itself could be read as a sign of softness or luxury, but in the painting it is first of all a luminous architecture for the head, an embodied light. If we demand a narrative, we risk missing the point: presence is enough when color and form are tuned.

Legacy and Relevance

“The White Feather” shows how modern portraiture can be both grand and spare. Without background details, props, or deep space, Matisse achieves monumentality. The work paved the way for his 1920s odalisques by demonstrating that costume and color fields could bear expressive weight independent of elaborate setting. It also anticipates mid-century portraitists who would rely on flat grounds and decisive shapes to deliver psychological effect. Most of all, it remains a model of pictorial ethics: choose a few elements, place them with care, and let color speak.

Conclusion

In “The White Feather,” Matisse distills portraiture to its essentials and finds abundance in restraint. A red plane, a pale hat with a cloudlike plume, a quiet face, and the most economical of dresses—these are enough to create an image that feels sovereign and immediate. The painting’s power lies not in storytelling but in the precise conversation between warm and cool, matte and luminous, curve and field. It is a demonstration of how color-built structure produces presence, and it reminds us that poise, when truly earned, needs very few words.