Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

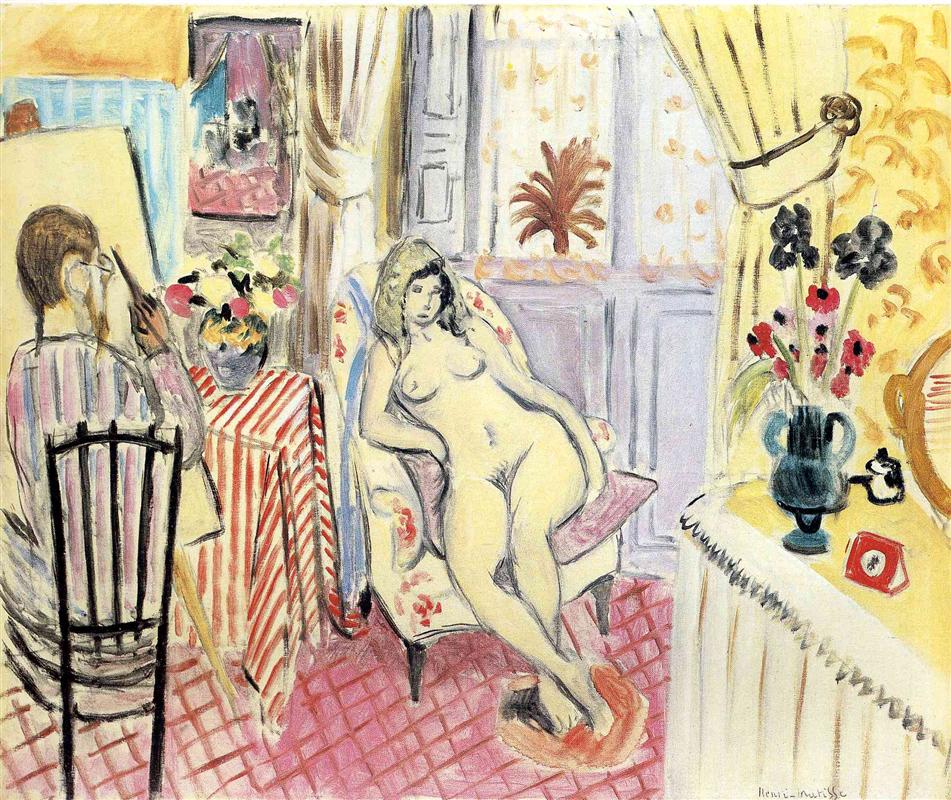

Henri Matisse’s “The Artist and his Model” (1919) is a lucid manifesto for the Nice period, the years when he rebuilt painting out of ordinary rooms, measured light, and the interplay of pattern and figure. The subject is as old as the studio itself: a painter at his easel and a reclining nude. Yet Matisse turns the familiar into a world of crisp intervals. A red-latticed floor carries the eye like a musical staff. A striped tablecloth tips diagonally through the middle distance. Curtains filter Mediterranean light into lavender panels, and yellow wallpaper on the right hums warmly against cool grays. At center, the model reclines in a floral armchair, one foot upon a blush rug. At left, the artist—seen from behind, striped smock echoing the tablecloth—raises his brush toward a large canvas. The room is at once domestic and theatrical, an interior turned into an instrument of color.

Historical Context and the Nice Turn

Painted in the first full year after the Armistice, this canvas belongs to Matisse’s early Nice decade. Having spent the prewar years proving how violently color could speak, he chose after the war to explore calm without blandness. In Nice he cultivated shallow spaces, patterned walls, shuttered windows, small tables, bouquets, and models resting on pale furniture. Decoration ceased to be surface frosting; it became the structural armature of the picture. “The Artist and his Model” extends that program into a reflexive scene about making. We are invited into the studio not to watch labor, but to feel how a tuned interior allows painting to happen.

First Encounter with the Scene

The composition divides into three zones. On the left, the painter and his tall canvas orient the action. In the middle, the red-and-white tablecloth scythes downward, a diagonal banner that anchors the central field beneath a mauve window and swags of curtain. On the right, yellow wallpaper and a console with a blue vase of dark blooms make a glowing margin. Between these wings reclines the model—pale, guarded by black contours, turned toward the painter and toward us—on an armchair whose floral upholstery repeats the bouquet’s motif at human scale. The floor’s pink lattice ties everything together: an oblique grid that keeps the shallow space legible and sets a steady tempo for the eye.

Composition: A Theater of Planes and Rhyme

Matisse treats the studio as a small stage. The red lattice is the floorboards of the theater; the striped tablecloth is a curtain pulled halfway aside; the window with its pale shutters becomes a luminous backdrop; the yellow wall on the right acts as a proscenium. The figures occupy opposite sides of the plot, each within a chair that rhymes in scale and form. The easel’s rectangle echoes the window’s rectangle and the console’s top; the table’s diagonal plays against the lattice’s skew; the curves of the model’s body replay in the armchair arms and urn handles. These rhymes ensure that every passage speaks to another, so the studio reads like one continuous sentence rather than snippets of furniture and flesh.

Pattern as Structure, Not Ornament

The Nice period taught Matisse that pattern could shoulder the duties of architecture. Here, the red lattice builds the floor plane and establishes recession; its rosy diamonds cool as they recede, implying depth without mechanical perspective. The tablecloth’s stripes run at a competing angle, producing a contained turbulence that energizes the center without loosening the whole. Floral upholstery on the armchair is not a sweetener; it is a pattern scaled to human presence, attaching the model to the room’s decorative system. On the right, the yellow wallpaper delivers a slow, warm counter-rhythm that keeps the cooler window from dominating. Pattern distributes attention; pattern keeps shallow space breathable.

Color Architecture and Temperature

Color carries meaning with the economy of a chamber score. A family of warms—yellows, corals, peach, ochres—balances a family of cools—lavender grays, powder blues, softened mauves. The lattice, the stripes, and the floral notes provide high chroma reds and pinks; the vase on the right brings dense blue-black; the bouquet on the striped table supplies saturated rose and lemon accents that calibrate the middle of the spectrum. Crucially, each color family recurs across forms: the pink of the floor enters the rug under the model’s foot; the lavender of the paneling shades the window, curtains, and even parts of the chair; the yellow of the wallpaper returns in the curtain tieback and the small red-edged clock on the console. Because colors repeat in different roles, the harmony holds and the eye recognizes order.

Light, Climate, and Mediterranean Calm

The room is bathed in tempered light. Windows and curtains diffuse it so that no violent shadows divide forms. Matisse turns volume by temperature rather than by heavy chiaroscuro: the model’s flesh warms at knee and cheek, cools along rib and thigh; the armchair’s white fabric reflects lavender from the paneling; the tablecloth’s red lightens where it catches air. The silver of light in the center keeps the atmosphere breathable. This climate—the antithesis of spotlight drama—allows color relationships to become the primary subject: how a cool gray sets off a coral stripe, how a black contour sharpens a pale plane, how yellow wallpaper can warm a scene from the edge.

The Artist: Presence Without Portraiture

The painter at left is unmistakably Matisse, yet his back-turned presence refuses self-drama. He is a functional actor in the picture’s rhythm—vertical rectangle of easel, upright posture, striped smock repeating the table’s motif, dark chair slats echoing the console vase. His head is a modest oval; his hand rises in a small arc; the brush is a short dark vector. This modesty is a principle. Rather than staging an heroic encounter with the nude, Matisse embeds the act of painting within the grander order of the room. The studio is not a stage for ego; it is an instrument tuned for looking.

The Model: Agency within Ease

The reclining nude is neither inert nor coy. Her pose, with one arm behind the head and one hand resting along the thigh, opens the torso to the painter and tilts the pelvis toward the viewer. The body’s planes are declared with direct, warm-cool passages and bounded by the living contour that Matisse perfected in Nice—a line that thickens where weight gathers and thins where light diffuses. The face, more specific than many Nice nudes, looks across the room with a composed, almost assessing attention. Because the armchair’s floral pattern shares her scale, she is not a body against décor; she is a participant in the room’s textile order. Agency resides not in overt gesture but in her integration with—and command of—the environment designed around her.

The Studio Still Life: A Central Motor

The small bouquet on the red-striped table, the dark blue vase on the console, the little red clock, and the palm-like plant in the window form a chain of still life passages that animate the room. Their colors cross the painting’s diagonals: roses and lemons echo in the model’s chair; the blue-black vase converses with the black slats of the painter’s chair and with the deepest contours around the figure; the cherry clock provides a sudden compact red to balance the broad floor. These objects tie the scene to domestic reality while fulfilling strictly pictorial jobs—beats in the rhythm, weights in the balance.

Drawing and the Living Contour

Matisse draws with paint, not with a pen. Contours of torso, knee, shoulder, and face are flexible and responsive; they do not imprison forms, they negotiate. Inside shapes he draws with temperature modulations and directional strokes: the abdomen turns on a cool mauve; the arm grows with a warm peach and a single cool highlight; the chair arm is a quick, dark hook filled with airy white. The lattice and stripes are briskly ruled—never mechanical, always hand-made. This living drawing keeps the painting present-tense. It lets viewers sense decisions rather than admire finish.

Brushwork and Material Presence

Across the canvas, touch varies with purpose. The floor is built from repeated, semi-dry passes that allow the ground to breathe through, producing a lightweight tile that supports rather than competes. The striped cloth is painted with faster, thicker strokes; you can feel the brush change direction at the table edge. Curtains are soft scumbles; paneling is pulled in long, gently cool strokes; the right-hand wallpaper is fluent, with the motif made of calligraphic loops that echo the bouquet’s stems. Flesh is the most various: blended where necessary, abrupt where the contour must assert. Everywhere, paint remains itself, never ground into anonymous illusion.

Space: Shallow, Habitable, Designed

Space is crafted to remain shallow and convincing. The lattice implies recession but closes it down before depth becomes a vista; the table’s diagonal supplies overlap; the model sits squarely within armchair arms; the console rises like a shallow shelf. The window promises exterior light yet acts primarily as a luminous panel, a hallmark Nice device. The result is a designed surface that one can imaginatively inhabit. You could step into that room, but you will never lose the painting as an object.

The Gaze and the Studio Triangle

Between painter, model, and viewer, Matisse builds a triangle of looking. The painter faces the canvas, which faces him; the model looks laterally across the room, acknowledging both painter and audience; the viewer stands at the fourth corner, addressed by the model’s gaze and welcomed by the room’s open choreography. Because the easel’s canvas is blank to us, we inhabit its place: we are where the picture-in-the-picture would be. This gentle mise en abyme pulls the outside world into the studio’s order and makes spectators collaborators in the act of seeing.

Rhythm and the Viewer’s Path

The painting conducts the eye along a deliberate circuit. Most viewers will begin at the model—brightest and most open form—then descend to the foot on its rug, cross the lattice to the striped table and bouquet, rise to the painter’s hand and canvas, glance at the small framed picture hanging beyond, and then drift back through curtains to the lavender window panel and down to the yellow wallpaper and blue vase at right. Each lap confirms new links: stripe to stripe, floral to floral, red to red, black to black. The picture becomes a practiced promenade, calm yet lively, like pacing a studio between brushstrokes.

Echoes with Other Works of 1919

This canvas speaks fluently with Matisse’s 1919 family. The red lattice floor appears in “Woman with a Red Umbrella” and several window interiors, always acting as a structural metronome. The pale, filtered window light and lavender paneling recur in “The Closed Window.” The relaxed nude relates to “Reclining Nude on a Pink Couch,” but here she is set not for reverie but for work, framed by the tools and textiles of painting. The dialog among these works reveals a method: repeat certain architectures across canvases so that variations in figure, color, and pattern can be heard clearly.

Palette and Likely Materials

The surface suggests a concise, traditional set of pigments handled for clarity rather than complexity. Lead white and touches of Naples for curtains, paneling tints, and flesh lights; alizarin and cadmium reds for the lattice and cloth; ultramarine and cobalt in paneling, shadows, and vases; yellow ochre and raw sienna for wallpaper and curtain warmth; viridian and sap green for floral passages; ivory black to fortify contours and deepen the bouquet’s centers. Paint is generally opaque, with transparent scumbles used to tame value and allow canvas grain to participate in light.

The Ethics of Clarity

“The Artist and his Model” proposes a way to live with images after exhaustion and fracture. There is no strain for novelty, no acrobatics of perspective, no melodrama between painter and subject. There is steadiness: patterns that hold space, colors that echo across distance, light that gives without glare, drawing that states rather than fusses. The studio becomes a place where care replaces spectacle, where order is made from ordinary things—a tablecloth, a chair, a window, a vase, a human body resting. This ethic of clarity is the quiet radicalism of Matisse’s Nice period.

How to Look Today

Stand close to feel the decisions: how one quick stroke anchors the model’s knee, how the contour fattens at the hip, how the stripe pivots at the table edge, how the wallpaper motif loops without repeating mechanically. Step back until the lattice merges into a pink field, the stripes into a diagonal wash, and the model becomes a single pale chord against lavender and yellow. Move again, letting your eye follow the picture’s practiced route. With each pass, the studio will feel more habitable, the colors more inevitable, the relation between work and leisure more intimate.

Conclusion

Matisse’s “The Artist and his Model” transforms the studio into a lucid system where color, pattern, and light do the real work of depiction. The floor’s lattice, the table’s stripes, the window’s pale glow, the wallpaper’s warm hum, and the armchair’s floral field collaborate to hold a nude and a painter in poised relation. It is a picture about painting that needs no slogans. Looking is enough, because the room itself has been tuned—like an instrument—to make harmony out of everyday forms.