Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

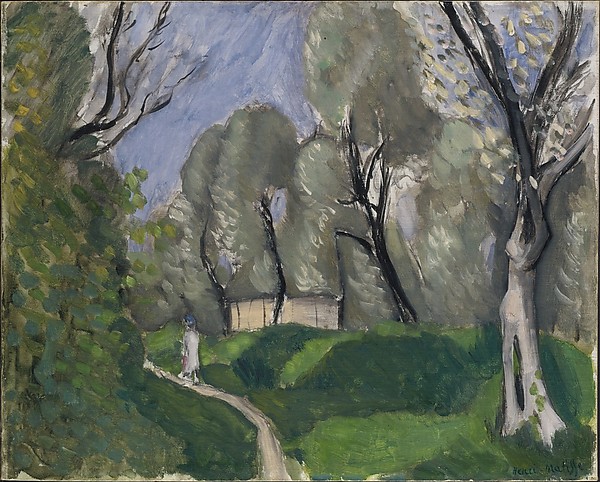

Henri Matisse’s “The Promenade” (1919) is a landscape that moves at a walking pace. A narrow path cuts through bright green embankments and leads the eye toward a pale wall tucked beneath a crown of closely planted trees. A single figure, small and calm, appears along the path—more measure than protagonist—while tall trunks on either side lean like sympathetic sentinels. The sky is a cool, violet-blue wash laced with milky bands, and the entire scene breathes a temperate, maritime light. With a restricted palette and broad, economical strokes, Matisse composes a promenade for the eye as much as for the strolling figure: a rhythm of curves, pauses, and returns in which nature is clarified into simple, decisive forms.

The Moment in Matisse’s Career

Painted in the first year after the Armistice, the canvas belongs to Matisse’s early Nice period. In these years he turned from prewar turbulence toward interiors and gardens bathed in Mediterranean light, seeking a durable harmony based on color relations and designed space. The landscapes of 1919 show him transferring that interior discipline outdoors. Instead of deep vistas, he builds shallow arenas framed by trees and hedges; instead of anecdote, he offers a climate—air, light, measured movement. “The Promenade” exemplifies this pivot. Its subject is the ordinary ritual of walking, yet the scene is arranged as carefully as one of his rooms. The path functions like a striped carpet, the trees like architectural piers, the sky like a painted frieze.

First Glance: A Stage for Walking

At first sight the painting reads as three stacked bands: a foreground of green slopes sliced by a path; a middle ground of pale wall and densely massed trees; and a high register of sky. But the divisions are softened by S-curves. The path flows from the lower left toward center, slipping behind a grassy bank and reappearing closer to the wall. Tree crowns billow into rounded volumes, like clouds lowered to earth, while the trunks angle inward, corralling the view. The figure—possibly wearing a light hat or scarf—acts as a punctuation mark that calibrates scale without demanding narrative. This is not a story about a person in a landscape; it is a landscape tuned to the tempo of a person.

Composition and the Architecture of Curves

Matisse organizes the composition with arcs and counter-arcs. The path’s long curve, the bulging mounds of grass, and the treetops’ domes lock together like articulated ribs. These rounded forms are steadied by stern, calligraphic trunks whose dark contours cut upward through the green. At the far center, the low wall forms a quiet horizontal that halts the path’s rise just enough to keep the space intimate. The overall effect is architectural without being rigid: a garden theater where movement is invited but never rushed.

Color as Structure

Color builds the space more decisively than line or perspective. The greens of the foreground are graded into two main registers: a bright, sun-warmed green that faces the light and a cooler, bluer green that slips into shade. The trees carry subdued, gray-green bodies edged by firm darks, so their masses read as solid yet breathable. The sky is a cool violet-blue modulated with pearly lanes; it refuses both high noon brilliance and twilight drama, settling instead into a kindly afternoon. The small figure introduces a brief vertical of cooler blue that resonates with the sky and gently offsets the surrounding chlorophyll. Because the palette is limited, relationships are legible: warm greens push forward, cooler notes recede, and the whites of exposed trunks and wall stitch light through the center of the picture.

Light and Climate

The light is evenly diffused—classic Nice weather that softens shadow and gives color room to sound. Instead of modeled cast shadows, Matisse relies on temperature shifts to turn forms: cooler green spilling along the backs of banks, warmer notes resting on sun-facing slopes, a faint violet chill seeping into the sky between tree limbs. The trunks, sometimes brushed with pale, chalky highlights, catch this light without sparkle, maintaining the painting’s gentleness. The atmosphere feels humid but clear, the sort of air that slows a walk into an attentive promenade.

Drawing and the Living Contour

Across the scene Matisse’s contour is elastic and visible. He tightens the line around trunks and branches, letting it thicken and taper like a pen stroke; elsewhere he relaxes the edge and allows planes of color to meet without border. The path is written in swift, confident sweeps and then softened where it disappears behind grass. The figure is reduced to a few notations—a vertical for the body, a flick for a hat—yet the posture is convincing. This alternation between declared edge and soft seam keeps the surface lively and prevents natural forms from dissolving into haze.

Brushwork and Material Presence

The paint sits in varied textures that correspond to substance. Grassy banks are laid in with broader, slightly dry strokes that catch the weave of the canvas, imitating the tick of blades without pedantry. The sky is scumbled thinly, letting undertones breathe through and producing a calm, breathable field. Trees receive denser, opaque passages that give their volumes weight. Dark branches and trunks are drawn wet-into-wet with assertive, calligraphic energy. Throughout, the evidence of making is allowed to remain; the painting feels discovered rather than manufactured.

Space: Shallow, Breathable, Modern

Depth is compressed by design. Overlaps—path in front of banks, banks before wall, wall before trees—supply sufficient recession, but the scene never opens into a grand vista. Instead, the eye circles among planes as if in a walled garden. This shallow construction reflects Matisse’s larger commitment to the picture plane. He preserves the canvas as a designed surface even while granting the viewer a believable place to walk. The promenade is both literal and pictorial: you move through the garden and through the architecture of color at the same time.

The Figure as Measure

The walker is small and nearly anonymous, but indispensable. Without the figure the banks might enlarge into abstraction; with the figure scale locks into place. The person’s presence also introduces narrative time—one step, then another—so the viewer reads the path not just as a shape but as a route. This measured human note speaks to the postwar ethos of recovery: not spectacle or heroic gesture, but a return to ordinary rhythms, to the sanity of walking a familiar path.

Trees as Decorative Columns

Matisse treats trees as both living organisms and ornamental columns. Their trunks are simplified into tapering, slightly twisted posts whose dark edges recall ink drawing; their crowns mass into rounded modules, each shaped by a few broad planes. The play between botanical truth and decorative clarity is quintessentially Matisse. It anticipates the cut-outs decades later, where leaves and branches would become pure silhouette while preserving their rhythmic life.

Rhythm and the Eye’s Promenade

The painting choreographs the eye along a clear path. One begins at the lower left where the path enters, glides along its pale ribbon to the small figure, then pauses at the low wall where the way narrows. From there the gaze rises into the dense trees, drifts left and right among their domes, and finally slips into the violet sky before returning down a trunk to the foreground green. Each lap feels like a breath: in through the path, out through the trees, in again through the sky’s cool lanes. This rhythm is the work’s true subject.

Dialogue with Tradition

“The Promenade” converses with centuries of French landscape, from Corot’s gentle parks to Cézanne’s constructed forests. Like Cézanne, Matisse builds form through planes of color and avoids theatrical depth; like Corot, he prizes temperate light and human scale. Yet his black calligraphic edges and his modern shallowness are distinctly his own. The result is a landscape that trusts design over description without severing its ties to lived nature.

The Role of the Wall

The pale wall in the middle distance is a small but strategic device. It marks the furthest reach of the path, anchoring the composition’s center and preventing the eye from wandering into an undefined distance. Its warm, creamy tone mediates between the cool sky and the warm greens, and its straight line brings a moment of human geometry to the field of curves. Like the figure, the wall is modest and decisive at once.

Season and Sensation

Though exact season is not specified, the light and color suggest early spring or late summer—the foliage is ample, yet the sky’s coolness and the trunks’ pale lichen hint at fresh, damp air. Matisse is not cataloging species or month; he is calibrating sensations: the bounce of turf underfoot, the damp cool along shaded banks, the mild warmth where sun spills across a trunk. The painting becomes a register of how a particular day feels when translated into paint.

Material Choices and Probable Palette

The surface indicates traditional, durable materials handled with restraint. Lead white likely provides the chalky highlights of trunks and sky; earth greens and ochres underpin the banks; a touch of ultramarine or cobalt leans the sky violet; ivory black or bone black sharpens the contours; small admixtures of earth red warm the wall and the most sun-struck greens. These pigments are not displayed for their own sake; they are tuned to the climate of the scene, mixed into a harmony designed to be read as one chord.

Comparison with Contemporary Interiors

Place this canvas beside Matisse’s 1919 interiors—rooms with red lattice floors, blue shutters, and parasols—and a common grammar appears. The path is the floor pattern; the trees are curtains or screens; the sky is the pale wall beyond an open door. In both cases Matisse designs shallow spaces that foster calm. The promenade, like the balcony picture, is an image of choosing one’s tempo and shaping one’s climate, whether inside or out.

The Ethics of Clarity

What feels modern here is not novelty but clarity. Matisse makes choices that keep relations legible: a few greens rather than many, trunks simplified to articulate the flow, a single figure to set the scale. He declines sensational effects—storm, dusk, dazzling sun—and instead builds a place where the eye can rest and travel. After the war’s noise, such lucidity reads as a form of care, a belief that order can be rebuilt from measured relations.

How to Look

Approach the painting as you would the path itself. Begin near the lower left corner and follow the pale ribbon as it curves. Notice how the green beside it warms and cools, how the trunk edges tighten then loosen, how the wall halts the rush and lets you lift your gaze into the domes of foliage. Let your eye idle in the violet sky; then descend a trunk and begin the walk again. The more slowly you circulate, the more the painting’s pulse reveals itself.

Lasting Significance

“The Promenade” has the durability of works built from essentials. It contains no topical markers, yet it bears the postwar desire for steady, humane places. It advances Matisse’s lifelong project—compressing the world into clear relations of color and shape—without sacrifice of sensation. And it foreshadows his late cut-outs, where leaf and branch would become pure arabesques against blue. Above all, it demonstrates how a painter can orchestrate an everyday act—walking—into an enduring visual music.

Conclusion

In “The Promenade” Matisse turns a bend in a path, a handful of trees, a wall, and a patch of sky into a complete, generous order. Curves guide and contain; color builds distance without spectacle; brushwork keeps the surface alive; a single figure sets the scale and the pace. The painting is modest in subject and ambitious in design, a landscape that teaches the eye how to move with calm attention. More than a view, it is an invitation—to look, to breathe, to walk a little more quietly through the day.