Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

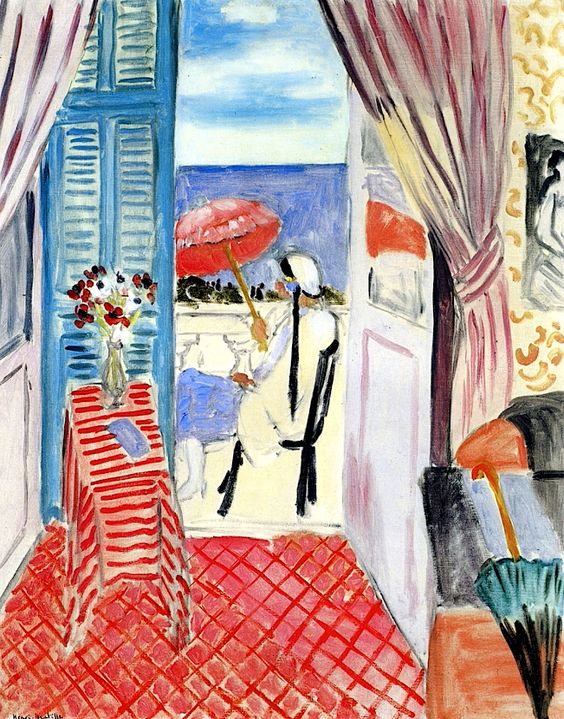

Henri Matisse’s “Woman with a Red Umbrella” (1919) is a radiant threshold painting in which the entire room seems to lean toward the light. We stand inside a small interior paved with a red lattice floor; to the left a narrow table dressed in a candy-striped cloth carries a clear vase of flowers; ahead, a doorway opens onto a balcony where a seated woman shelters under a crimson parasol; sky and sea compress into a bright horizontal beyond. Blue shutters, mauve curtains, and a few dark accents frame the view the way proscenium wings frame a stage. The image is intimate yet expansive. With a few decisive colors and patterns, Matisse turns a simple seaside moment into a complete orchestration of space, rhythm, and climate.

Historical Context

The painting belongs to Matisse’s early Nice period, completed in the first peacetime year after the Armistice of 1918. During these years he turned to interiors and balconies along the Côte d’Azur, answering an exhausted Europe with images of calm and measured light. Rather than narrative drama, he developed a language where color builds architecture, pattern supplies tempo, and ordinary rituals—reading by a window, resting on a couch, shading one’s face with a parasol—carry the dignity of renewal. “Woman with a Red Umbrella” ties the period’s key motifs together: the room as sanctuary, the balcony as threshold, the sea as open horizon, and the parasol as a pocket of chosen shade in a sunlit world.

The Motif And First Impression

At first glance the composition reads as a corridor of color pulled toward the balcony. The red floor’s grid ushers the eye forward. The table at left and the curtained wall at right form lateral guards that steer the gaze to the opening. The woman outside is both near and far—near because we share her climate of light and air, far because she sits beyond the balustrade in her own circle of shade. The parasol blooms like a flower echoing the bouquet inside, so interior and exterior mirror each other. The painting proposes a duet: room and terrace, pattern and horizon, human comfort and vast air.

Composition As Processional Space

Matisse constructs a processional path from foreground to vista. The floor, a diagonal net of red over pale pink, compresses space while maintaining a sense of forward glide. The table’s stripes run counter to the lattice and introduce a second rhythm, vertical where the floor is diagonal. The bouquet’s rounded heads add syncopation atop those stripes, preparing the eye for the roundness of the umbrella outside. On the right, mauve curtains sweep back to reveal the doorway, their curved folds echoing the arc of the parasol; a darker, upholstered piece with a folded green umbrella provides a weighty pause before we enter the sun. The central opening is narrow and tall, squeezing the view so that the sea and sky appear as bands of distilled color. Everything funnels outward without hurry.

Color Architecture And Temperature

The palette is designed as a warm-cool equilibrium. Red dominates the interior: the floor’s lattice, the tablecloth’s stripes, and small echoes on the wall and cushion. Blue and turquoise cool the left wall and shutters, while the balcony’s light and the distant water lean toward softer azure. The doorway’s inner jamb warms to pale rose, mediating between the scarlet interior and the cool vista. The parasol takes a center place in this temperature map. Its red unites inside and outside, creating a chromatic bridge that prevents the balcony from feeling detached. The creamy whites of dress and table reflect light throughout, while small black lines—chair legs, the woman’s profile, the balcony’s rail—tighten the composition like quiet armatures. Because each color family shifts in value and temperature, the harmony breathes rather than hardens.

The Balcony As Threshold

Matisse’s balcony paintings almost always stage the negotiation between interior order and exterior openness. Here that negotiation is literal. Inside, pattern is dominant: stripes, lattice, and drapery folds legislate the eye’s movement. Outside, shapes simplify: a seated silhouette, an umbrella’s circle, a horizontal of sea, a smudge of distant land. The balustrade is omitted, as if we have already stepped through it in our minds. The result is a gentle oscillation—one can inhabit the room’s comfort and then step, with a glance, into the airy expanse beyond. The painting becomes a lesson in how vision crosses thresholds.

The Table, Flowers, And Mirror Echo

The small table at left is an essential actor. Its rhythmic stripes lean downward toward the doorway, guiding the eye to the balcony. On its top, a small vase of flowers repeats the parasol’s warm notes in miniature, establishing a visual rhyme across the opening. A blue book or folded cloth lies beside the bouquet as a cool counterpoint. The table’s scale matters: it is narrow enough to avoid blocking the view, yet tall enough to assert presence. In this intimacy—a few stems, a striped cloth—Matisse gives the room a pulse of everyday care that foreshadows the quiet attention of the woman outdoors.

The Woman And Her Red Umbrella

The figure is defined by economy. A white dress occupies the center of the opening, trimmed by a black sash and hat; the chair is little more than a set of dark strokes. The parasol is the most substantial form outside, painted with brisk arcs that allow bits of sky to sparkle through at the edge. It is both practical sunshade and pictorial engine, gathering indoor red into the exterior and softening the brilliance of the balcony light around the sitter’s face. Because her features are unelaborated, her presence reads through posture: a person at ease in a chair, enjoying the shade she has created. The umbrella does not hide her; it dignifies her choice to curate her own light.

Pattern As Structure Rather Than Ornament

Pattern, in Matisse’s hands, is never decorative excess. The floor’s lattice is a structural grid that defines the room’s plane and pulls the viewer forward. The table’s stripes establish a vertical counter-rhythm and a firm silhouette for the still life. The curtains’ pleats provide slow, theatrical arcs that keep the doorway from feeling cut out. Even the left shutters carry linear repetition—horizontal slats that echo the sea’s horizon and keep the cool plane alive. Against these busy fields, the balcony simplifies; the alternation prevents restlessness and clarifies the figure.

Light And Atmosphere

Mediterranean light pervades the painting, yet Matisse keeps its brightness humane. There are few hard shadows; that choice frees color to carry volume. The interior receives a steady wash that lets reds glow rather than flare. The balcony is whiter and more open, but the umbrella tempers the glare and returns warm color to the exterior. The sky sits tenderly, a mixture of pale blue and milky white; the sea band is deeper, rendered in lateral strokes that hint at breeze. This is daylight tuned for living—a climate in which pattern can sing without shouting.

Space And Modern Flatness

Perspective exists only insofar as it helps clarity. The floor’s grid offers recession but not strict orthogonals; the table tilts slightly; the doorway narrows to frame the view. Most of the picture is organized by overlapping planes and color parallels rather than by classical depth cues. The strategy keeps the surface alive, reminding us that this is paint—an artifact with its own set of truths—while still granting the agreeable fiction of a room open to a terrace and sky.

Drawing And The Visible Hand

The drawing is frank. Matisse lets linear decisions remain legible around the shutters, chair legs, parasol rim, and table edge. These quick darks act like musical bar lines, holding the color’s melody in time. At the same moment, many passages are painted thinly enough that the canvas weave participates in the surface—especially in curtains and the blue wall—so the image retains the freshness of first decisions. This visible hand aligns with the subject: a room not staged to perfection but truly lived in.

Rhythm And The Viewer’s Path

The painting choreographs the eye with deliberate rhythms. Most viewers begin at the umbrella’s red circle, fall down the parasol’s shaft to the sitter’s hand, travel back across the opening to the vase and tablecloth, descend the table stripes to the lattice floor, and follow its diagonal toward the right curtain before returning up to the balcony’s light. Each loop gathers new correspondences—red echoing red, blue answering blue, curved parasol answering curved drape—until the room’s pulse becomes palpable. The path is not a tour of objects; it is a movement through designed relations.

Dialogue With Tradition

The image nods to Impressionist balcony scenes and to the parasol motif beloved by Monet and Renoir, but Matisse modernizes the subject by emphasizing flat organization over atmospheric fracture. The terrace is not an explosion of light; it is a scored harmony of planes. The interior patterns remember the decorative arts of the nineteenth century, yet they are deployed as architecture rather than embellishment. Matisse honors the social history of seaside leisure while disentangling it from anecdote. The parasol becomes a circle of color that stabilizes the whole painting, not a prop laden with story.

Human Presence And Privacy

Despite the open view, the painting preserves the sitter’s privacy. We see no detailed face, no narrative cues beyond posture. She is someone in her own weather, not a spectacle. The interior’s bouquet and closed book echo that tone of quiet attention. Even the extra umbrella leaning at lower right hints at domestic rhythm—objects kept ready for living rather than arranged for show. The scene respects the person’s agency while inviting us to share the room’s climate.

Material Truth And Tactile Variety

Matisse differentiates materials through handling. The red floor is dragged and scumbled, suggesting the slightly chalky surface of tiles in sun. The striped cloth is painted with firmer, parallel strokes that convey woven regularity. The glass vase is made with a few luminous accents that stand out from the matte cloth beneath it. The parasol carries semi-opaque reds thin enough for light to glint along the rim. This tactile variety convinces without illusionism, sustaining the painting’s balance between description and design.

Anticipations Of Later Work

The clear silhouette of the umbrella, the insistence on patterned planes, and the shallow layered space foreshadow the cut-outs of the 1940s, where leaves, waves, and dancers become pure shapes pinned to color. “Woman with a Red Umbrella” already treats pattern as structure and figure as emblem—ideas that will later bloom in paper. Here, however, oil’s softness allows transitions that paper will trade for crisp edge, keeping the room intimate and airy.

How To Look Today

The painting rewards slow seeing. Allow the interior reds to settle in the eye; notice how the balcony’s white cools them; linger over the points where warm and cool touch—the doorway jamb, the shadowed pleats of the curtain, the umbrella’s underside. Trace the stripes until they become a metronome for the gaze, then release into the sky’s quiet band. That alternation between pulse and rest is the painting’s gift: it models a way to move through a day with attention and ease.

Conclusion

“Woman with a Red Umbrella” is a lucid summation of Matisse’s Nice-period promise. A modest interior, a luminous opening, a human figure under a handmade climate of shade—these elements are arranged with such clarity that they become perennial. Color provides the architecture, pattern the rhythm, light the breath. The painting offers a vision of domestic life porous to the world, where the eye can walk out to sea and back again without leaving the room. Its harmony is not an evasion of reality but a carefully built order in which looking itself becomes a form of renewal.