Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

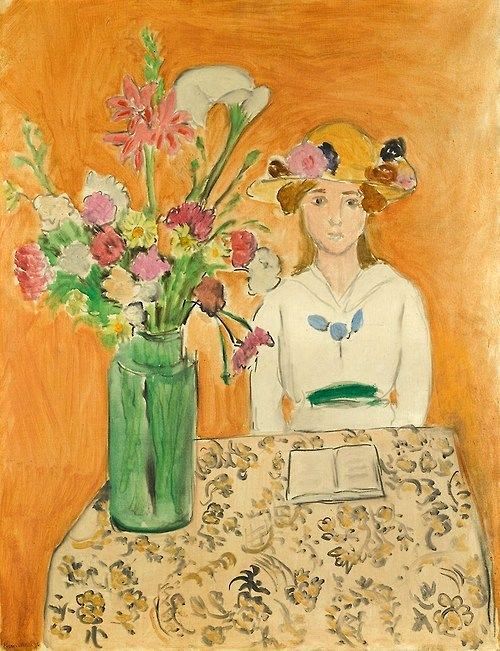

Henri Matisse’s “Girl in White with a Bouquet” (1919) is a poised duet between a person and a still life. A young girl sits at a patterned table in front of a warm orange wall; to her left a tall green glass vase brims with fresh stems and blooms; an open book rests before her like a pause mark. The image is modest in subject yet expansive in feeling. With a handful of colors—orange, green, white, and a scatter of floral reds and violets—Matisse composes a room that breathes. The canvas distills the promise of his early Nice period: domestic quiet staged as color architecture, pattern used as structure, and a human presence centered not by detail but by the clarity of relations.

Historical Context

Painted the first year after the Armistice, the work belongs to Matisse’s postwar turn toward interiors and everyday rituals. During 1919 he repeatedly explored women at tables, bouquets in tall vases, shutters and balconies, nudes on pink couches, and readers in calm rooms. These scenes are not escapist; they answer the need for equilibrium after upheaval. In Nice, Mediterranean light lent itself to soft transitions and calm palettes. “Girl in White with a Bouquet” harnesses that light to illuminate the dignities of ordinary life—reading, looking, sharing space with flowers—activities that rebuild time and attention.

The Motif: Portrait and Still Life as Partners

Matisse fuses portrait and still life without allowing one to dominate. The bouquet is an equal protagonist, not a prop, and the open book gives the figure a credible task even as it serves the composition. The young sitter wears white with touches of blue at the chest and a green sash at the waist; a straw hat trimmed with blossoms echoes the flowers beside her. This doubling—flowers in the vase, flowers on the hat—binds figure and arrangement into a single decorative logic. The painting invites us to read both faces: the person’s and the bouquet’s.

Composition as Stagecraft

The design is a shallow stage built from three large planes: the orange wall, the patterned tabletop, and the vertical block of the vase with its bouquet. The girl sits slightly off-center to the right, counterbalancing the tall green mass at left. The open book anchors the lower middle, creating a small, pale rectangle that holds the viewer’s focus before it rises toward the face. The curve of the hat and the tall sweep of a white flower arc toward each other, forming a soft gate around the head. Everything is cropped decisively; no space is wasted, yet the scene never feels cramped because the color fields keep air moving through the frame.

Color Architecture and Temperature

Color builds the picture from the ground up. The orange background is the painting’s climate—warm, steady, and luminous rather than loud. Against it Matisse sets the cool green of the vase and sash, which insert depth and calm. The girl’s white dress is a mediator, catching glints of surrounding hues and sending them back into the room. Floral notes—rose, carmine, lilac, creamy white—spark through the bouquet and repeat, lightly, on the hat. The patterned tablecloth subdues its own yellows and browns to sit harmoniously between wall and vase. Nothing is strident; each color family varies in value so harmony feels alive rather than flattened.

The Bouquet: Pattern Turned Vertical

The bouquet is built with Matisse’s characteristic economy. Thick, confident strokes plot the heads of flowers while thin, darting lines state stems and leaves. He avoids floristic specificity—these are garden types rather than botanical portraits—but he gives the arrangement convincing weight and outward movement. One tall white bloom leans left, several pinks and reds press outward, and small violets flicker near the rim. The ensemble reads as a vertical pattern, a living counter to the horizontal expanse of table and book. Because the bouquet is a column of variation rather than a counted cluster, it keeps the painting’s tempo flexible and musical.

The Green Glass Vase

The vase is a study in how little information is required to persuade the eye. Interior reflections and darker verticals imply thickness and water without fussy highlights. A single bright accent along one edge describes the glass’s curve. The height of the vessel matters: it lifts the bouquet so that flowers share the sitter’s horizon line, allowing a conversation between faces. Green is also the strategic complement to the orange wall, creating a classical harmony that grants the scene balance and depth.

The Girl: Presence Without Theatrics

The sitter’s features are stated with few touches—eyes, nose, and lips simplified into planar notations—yet she holds attention through posture and placement. Her white blouse opens in a small V, a blue ornament or bow rests at the chest, and a green sash cinches the waist. These two colored accents rhyme with vase and bouquet. The face is painted with tender transitions rather than hard lines; the expression is reserved, neither smiling nor withdrawn. Matisse grants her privacy even as he centralizes her presence. It is a modern portrait stance: not a narrative character, but a human measure for color.

The Hat and the Echo of Flowers

The straw hat with its blossom trim plays a critical compositional role. Its warm, ochre band and flowered brim echo the bouquet’s palette, translating the vertical abundance of the vase into a compact horizontal crown. The hat’s upper arc is one of the painting’s most elegant lines, and the small flowers around it punctuate the head’s silhouette without burdening the face with detail. The hat thereby becomes a hinge, linking the portrait to the still life and repeating the painting’s thesis that ornament can be structure.

The Patterned Tablecloth

The tabletop is a decorative field that stabilizes the scene. Its motifs—dark rosettes, leaf shapes, and small spirals—are painted as shorthand signatures, not counted textiles. Because the pattern is distributed evenly, it reads like a low musical hum that supports the larger notes of vase, book, and figure. The cloth’s color sits between the orange wall and green vase, a middle register that keeps the composition from splitting into warm and cool camps. The tablecloth also establishes scale; its repeating forms make the vase’s height and the book’s smallness legible at a glance.

The Open Book

The open book on the table is both narrative and formal device. Narratively it grants the figure an activity—a paused reading—without forcing expression. Formally it provides a pale, rectilinear anchor amid arabesques of flowers and pattern. Its pages reflect the wall’s light and return it, subtly, to the sitter’s face. The book’s tidiness calibrates the room’s calm: this is a space for attention, not clutter.

Space, Depth, and the Modern Picture Plane

Depth is held shallow on purpose. The wall sits close behind the figure; the table rises toward the picture plane; the vase stands on the same shallow stage as sitter and book. Overlap—vase before wall, figure before wall, book before cloth—supplies enough perspective to inhabit, but never enough to eclipse the painting’s surface design. This balance between believable room and decorative flatness is the Nice period’s hallmark and the source of its serenity.

Light and Atmosphere

Light in the painting is stable and generous. It arrives evenly across wall and tabletop, finding slight brilliance in the white dress and the vase’s glassy edge. There are few hard shadows; modeling is achieved through temperature shifts and the direction of brushstrokes. This soft climate preserves color relationships and makes the scene feel breathable. The flowers glow rather than sparkle; the book sits without glare; the girl’s face holds volume without deep shadow.

Drawing and the Living Edge

Matisse’s drawing is elastic. He uses a soft dark to trace the edge of the blouse, the brim of the hat, and the contour of the vase; elsewhere he lets planes meet without outline, especially in the face where color-to-color transitions do the work of form. The pattern on the cloth is written with quick, calligraphic marks that keep the surface animated. The overall effect is decisiveness without rigidity—edges that steady the image yet allow it to breathe.

Brushwork and Material Presence

The paint sits thinly in the wall and cloth, letting the canvas weave play through warm washes. It thickens around blossoms and at key accents on glass and hat flowers. These variations deliver tactile truth: fabric feels soft because the paint is scumbled; flowers feel fresh because the touch is quick and wet; glass feels cool because highlights are spare. The visible hand provides honesty and keeps the portrait present-tense; we encounter a scene made before our eyes rather than a polished fabrication.

Pattern as Structure, Not Decoration

Throughout, pattern is functional. The tablecloth’s arabesques distribute weight across the bottom third; the bouquet’s variety holds the left vertical; the hat’s floral trim keeps the head rhythmically alive. None of these patterns operate as ornament piled on; they are scaffolds that carry space and rhythm. Matisse’s genius lies in letting decoration do the work of architecture while remaining joyful.

Dialogue with Tradition

The painting converses with a lineage of French interiors—Chardin’s still lifes, Manet’s tables, Morisot’s readers—while clearly voicing Matisse’s modern priorities. Like those predecessors he respects the ordinary object; unlike them he uses large color fields and simplified forms to install calm rather than incident. The bouquet-and-figure pairing also nods to his own earlier Fauvist works, but the heat has been tempered. What remains is conviction: color as structure, harmony as subject.

The Viewer’s Path

A natural route through the picture begins at the bright bouquet, descends the vase to the book, crosses the tabletop pattern to the girl’s sash, and rises to the face and hat before returning to the flowers. Each circuit slows, revealing small counterpoints: a blue accent at the collar that answers the violets in the bouquet, a green note in the sash that resonates with the vase, a warm stroke around the hat brim that repeats the wall. The path teaches the viewer how to look at the scene with the same sustained attention the open book implies.

Meaning and Resonance Today

For contemporary viewers the painting offers an image of composure. It proposes that a room tuned by color and attended objects can host thought. The flowers are not luxury but courtesy; the book is not symbol but practice; the hat is not costume but rhythm. The painting dignifies these small arrangements and shows how they might bring order to a day. Its modernity lies in this ethic of attention, not in any shock of novelty.

Conclusion

“Girl in White with a Bouquet” is a lucid essay in Matisse’s Nice-period language. A warm wall, a green vase, a patterned cloth, an open book, and a young sitter arranged with care become a scene of durable calm. Pattern is harnessed as structure; color carries space; light breathes evenly; the human presence is centered without melodrama. The painting does exactly what postwar Matisse hoped art could do: restore a sense of hospitable order through clear, joyful relations of form and hue.