Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

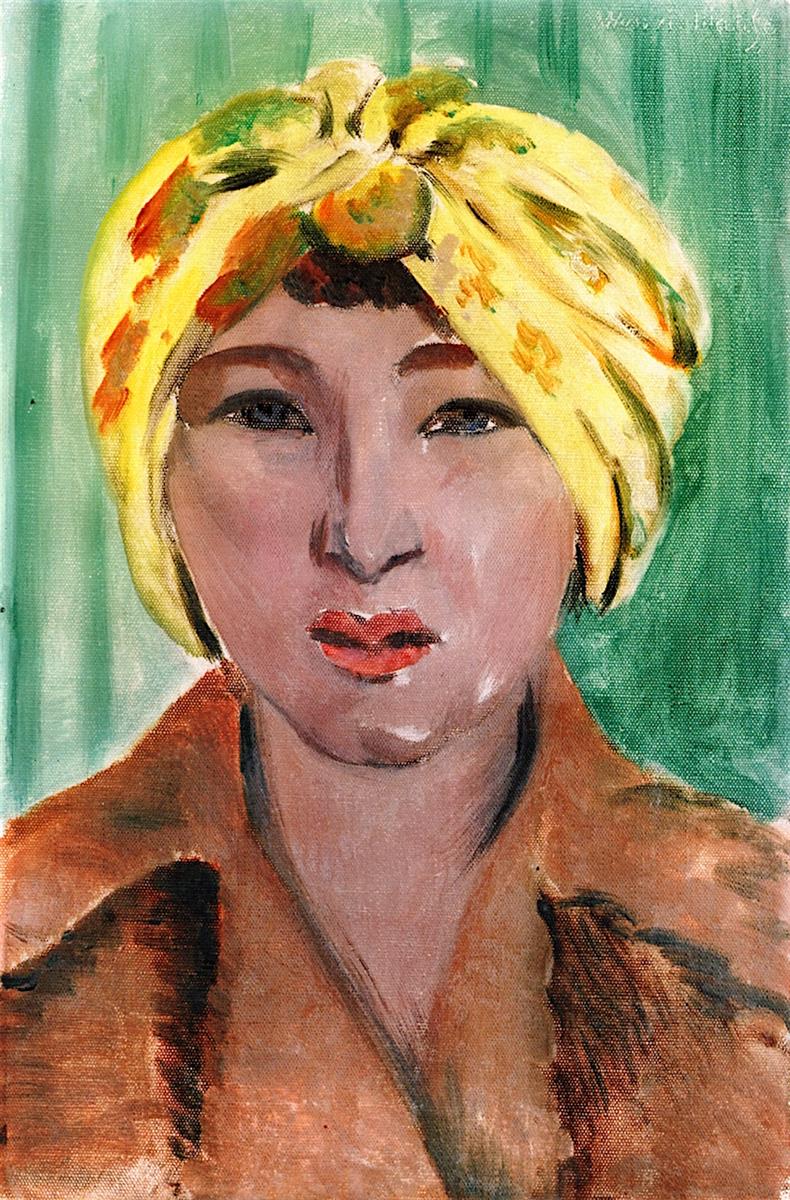

Henri Matisse’s “Portrait of Yvonne” (1919) delivers a direct, close-quarter encounter with a sitter whose presence is concentrated into a few decisive planes of color. A bright lemon-yellow turban wrapped tightly around the head, a tawny coat that reads as plush and tactile, and a cool green field behind the figure establish a compact harmony of complementary tones. The face is simplified rather than miniaturized, modeled with broad transitions of rose, mauve, and pearl gray; the lips are a saturated coral accent; the eyes are written in quick, telling shapes. Everything about the canvas feels immediate—brushstrokes that hold the weave of the fabric, edges that breathe, color pitched to carry emotion with minimal means. It is a portrait of character built from color decisions, and a statement of Matisse’s postwar clarity as he enters the Nice period.

Historical Context

The year 1919 marks a hinge in European life and in Matisse’s trajectory. The Armistice had arrived only months prior, and the artist, shifting his base to the Mediterranean, turned away from prewar turbulence toward rooms, models, fabrics, and quiet acts—reading, resting, looking out a window. These pictures temper the blaze of Fauvism while preserving its conviction that color is the true armature of painting. “Portrait of Yvonne” belongs to this restorative turn. The format is intimate and frontal; there is no elaborate setting, no symbolic stagecraft. Instead the portrait asserts that a handful of hues—green, yellow, brown, and the living notes of flesh—can rebuild a human presence with surprising authority.

The Motif and First Impressions

The picture offers a cropped head-and-shoulders view, the sitter centered and level with the viewer’s gaze. The yellow turban is the most striking element, tied high with a knotted crest that produces a small starburst at the crown. Beneath it, a fringe of hair forms a warm, dark arch. The coat or wrap occupies the lower third in reddish browns, its surface described with scumbled passages that suggest a soft nap. Behind, vertical swaths of cool green set the figure in relief. This is not a portrait wrapped in anecdote; it is a study in the dignity that can be achieved when color, contour, and touch are tuned to one another.

Composition as Architecture

Matisse builds the image as if it were an architectural façade. The rectangle of the canvas is divided into three principal zones: the green field of the background, the oval mass of head and turban, and the triangular wedge of coat that points upward toward the face. The centrality of the head gives the structure calm; the acute angles at the shoulders and collar add a gentle counter-rhythm. The composition’s stability allows the energy of brushwork to remain readable without tipping into agitation. Cropping is decisive: the figure fills the frame so fully that there is little air to spare, heightening immediacy and eliminating any potential narrative clutter.

Color Architecture and Temperature

The portrait is organized by complementary temperature contrasts. The cool green backdrop, brushed in vertical pulls, feels like a curtain of soft light. Against it, the yellow turban radiates warmth, leaning toward golden citron with touches of orange and olive. The skin tones negotiate between these poles—pearly, slightly cool planes around the eyes and nose set against warmer notes on cheeks and lips. The coat, a sturdy reddish brown, grounds the image in the lower register and binds the warmth of the turban to the human body beneath it. Because Matisse reduces the palette to a few families of color and avoids stray accents, relationships become legible: cool surrounds warm, warm anchors cool, and flesh breathes between.

The Turban as Emblem

The turban is more than adornment. It is a color engine and a cultural echo. Matisse’s love of textiles from North Africa and the Near East often found its way into Nice-period interiors; here that taste is distilled into a single garment. The yellow fabric, daubed with orange and green, introduces a repeating motif—small petallike marks—that catches and redirects light. Formally, the turban’s high knot lifts the portrait’s center of gravity and frames the sitter’s eyes; psychologically, it grants the figure poise, a sense of self-possession that resists the vulnerability of close frontal portraiture. It becomes the painting’s crown and the hinge around which all other colors revolve.

Drawing and the Living Contour

Matisse’s drawing is present and economical. A supple, dark line marks the edges of the turban, brows, eyelids, and lips; elsewhere, forms are joined by meeting planes rather than by drawn borders. The nose is a single vertical turn that splits into two small wings; the lips are defined by a soft, lifted bow and a darker seam; the eyes are written with the barest notation of lids and irises. The coat’s collar is a few quick planes that read as plush because of their blunt edges and the drag of a loaded brush. This alternation—line when necessary, paint when sufficient—keeps the portrait alert without over-articulating anatomy.

Brushwork and Material Presence

The surface of the painting matters as much as its image. The green background preserves the weave of the canvas beneath thin, translucent strokes, which allows the color to glow from within. The turban is painted more densely, with crisp dabs and small slashes that catch on the fabric’s imagined folds. The face is handled with thin veils of color smoothed by the brush then revived by smaller, more assertive touches at the eyes, nostrils, and lips. The coat is scumbled and dragged, creating a tactile nap that stands apart from the smoothness of skin. These differences in handling transform materials into sensations: cloth reads as cloth, flesh as flesh, even though neither is descriptively detailed.

Light and Atmosphere

The light is soft, likely from a high window, and it behaves not as a spotlight but as a gentle wash that clarifies the planes of the face. Highlights are moderated: a small shine at the lower lip, a faint gleam near the tear ducts, a slightly cooler value along the bridge of the nose. Shadows are warm and transparent, never thick or black. This tender illumination is characteristic of Matisse’s Nice period, where Mediterranean light is filtered through curtains and absorbed by textiles before it reaches the sitter. The result is a climate in which color thrives and skin retains its living temperature.

Modeling Through Planes, Not Detail

“Portrait of Yvonne” reveals Matisse’s preference for constructing the head with broad planes rather than with minutiae. The forehead is a single tilt; the cheeks are two angled, warm fields; the chin is a rounded wedge joined by a narrow, cooler note at the throat. In a few places—around the eyes and lips—he augments these planes with small accents to convey focus or softness. This approach sidesteps photographic description in favor of sculptural clarity. The face reads as solid and present, yet no single feature has been belabored; character emerges from the whole.

Expression and Psychology

The sitter’s expression is poised, alert, and slightly withheld. The eyes meet us, but not with aggression; the mouth is firm, the corners neither lifted nor dropped; the brows are relaxed. The portrait’s psychology arises less from an encoded emotion than from posture and color. The boundary set by the turban and coat protects the face, while the cool background sets it forward. That interplay of shelter and projection—warmth gathered inside, cool air outside—produces a dignified reserve. We encounter not a specific narrative but a person confident in her self-containment.

Space and the Modern Picture Plane

Space is minimal and modern. The background is a flat, breathing field, not a recess with measurable depth. The head floats a short distance from it, separated by temperature and by the strength of contour. This shallow arena keeps the painting close to the surface where color distinctions and the vitality of brushwork can carry form. The viewer does not enter a room; the room presses toward the viewer, and the sitter occupies that slim, brightly lit zone between.

Ornament and Plainness

Matisse balances the ornamental and the plain with precision. The turban, speckled with orange and green, supplies the only explicit pattern, while the background and coat are broad fields with subtle variation. The face itself is mostly plain, a calm stage onto which small ornamental accents—the quick dark of the lashes, the necklace-like rhythm of the upper lip’s bow—are placed sparingly. The balance prevents the portrait from tipping into mere fashion study and maintains focus on the sitter’s presence.

Relation to the Nice Period and Companion Works

As a head-and-shoulders image, “Portrait of Yvonne” sits alongside the era’s seated portraits and odalisques, but its compression and frontal encounter make it distinct. Compared with “The Green Sash” or “The Green Dress,” this painting narrows the frame and intensifies the chromatic argument. The extravagant textiles and elaborate studio settings of other Nice pictures are here distilled to essentials: a single textile (the turban), a single grounding garment (the coat), a single field of color behind. That distillation reveals just how much expression Matisse could wring from a reduced vocabulary.

Dialogue with Tradition

Matisse’s portrait engages longstanding traditions while keeping faith with modern simplification. The frontal format remembers Byzantine icons and Fayum mummy portraits, where a face addresses the viewer directly. The turban nods to orientalist costume painting yet avoids its fantasies by refusing narrative props. The insistence on flat color and clear edge acknowledges Manet and Cézanne—predecessors who taught that a painting’s truth lies in the constructed surface. “Portrait of Yvonne” participates in this lineage by letting color planes do the work of likeness.

The Ethics of Economy

A striking aspect of the canvas is its restraint. Every addition would cost the portrait clarity; every subtraction would risk anemia. Matisse arrives at the necessary middle: just enough modeling to hold the head in space, just enough pattern to animate the turban, just enough background modulation to suggest air. This economy is not minimalism for its own sake; it is a form of respect—for the medium, which should not be forced into illusion, and for the sitter, who should not be drowned in descriptive chatter. The result is a humane frankness.

Materiality and the Visible Weave

The canvas weave is deliberately visible in many passages, especially the greens of the background. That texture becomes part of the color’s life, breaking the strokes into fine lattices that catch light and keep the field active. In places where the paint is thicker—on the turban knots and coat’s shoulder—the weave recedes beneath a small relief of pigment, offering a counter-sensation. This material variety gives the portrait physicality; it reminds the viewer that the face we meet is an event on cloth, and that this physical truth is inseparable from the psychological one.

The Viewer’s Path

Looking at the portrait tends to follow a steady loop. The eye usually begins at the small starburst of the turban’s knot, descends along the arc of hair to the eyes, rests on the coral of the lips, slides to the warm collar and the dark pocket of shadow at the shoulder, then rises through the coat’s soft planes back to the turban. This circular route reinforces the painting’s equilibrium and gradually reveals the micro-harmonies—green echoes in the turban that answer the ground, warm flecks in the background that greet the coat, cool grays that temper the rose of the cheeks.

Time and the Sense of Occasion

Although there is no narrative action, the portrait carries a sense of occasion. The turban suggests a moment prepared for rather than an accidental glimpse; the coat implies a threshold between indoors and out. Yet the handling of paint is so fresh that the occasion feels present tense—perhaps a few minutes in the studio, a brief sitting during which both painter and model aimed for concentration rather than ceremony. This combination of formality and immediacy is a key pleasure of the work.

What the Portrait Offers Today

For contemporary viewers, “Portrait of Yvonne” offers an alternative to photographic likeness: a vision in which character emerges from color relations and touch. The painting models the virtues of attention—how looking carefully at a handful of hues and edges can yield an image more alive than detail for its own sake. It invites slow viewing, the kind that registers temperature shifts and brush pressure, and in doing so it proposes a way of meeting other people: notice the essentials; honor economy; grant dignity through clarity.

Conclusion

“Portrait of Yvonne” is a compact demonstration of Matisse’s mature faith in color as structure and in economy as grace. A bright turban, a tawny coat, a green field, and a face modeled with a few planes—these ingredients, ordered with care, produce a presence that feels both immediate and enduring. The portrait’s modernity lies not in shock but in poise: a shallow space, a visible surface, a chromatic architecture that lets a person come forward without theatricality. In the wake of upheaval, Matisse found stability in such clear encounters. The painting still offers the same gift: an invitation to meet another human being, fully, through the disciplined pleasures of looking.