Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

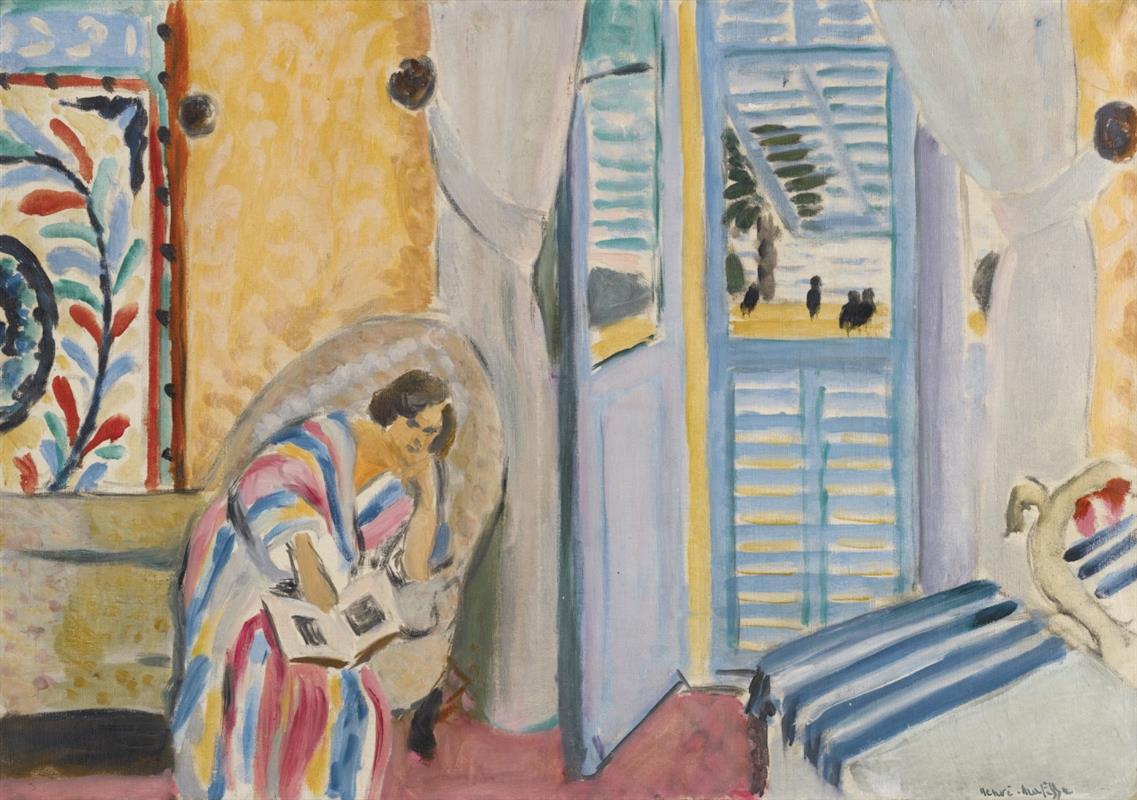

Henri Matisse’s “Woman With a Book” (1919) stages a gentle drama of attention inside a sun-washed room. A woman in a striped robe sits curled into a wicker chair, head propped on her hand, reading. To her right, pale curtains gather around an open door with light-blue shutters; through the slats a sliver of exterior life—palm, sky, a few dark figures—flickers like a distant melody. A patterned hanging at the far left, a rose-colored floor, and a bed topped by blue-and-white stripes complete the domestic theatre. The scene is neither grand nor overly intimate; it is a portrait of a morning’s rhythm, when air moves through a room and a book sustains a person’s inward journey. Painted at the beginning of Matisse’s Nice period, the canvas condenses his mature beliefs: that color can build space, that pattern is a structural force, and that ordinary acts—reading, resting, looking—can carry deep visual music.

Historical Context and the Return to Interiors

The year 1919 sits just beyond the Armistice of November 1918. Europe is exhausted; artists search for steadier subjects. Matisse relocates his center of gravity to the Mediterranean, where clarity of light encourages clarity of design. Instead of polemics, he cultivates rooms, screens, balconies, and decorative fabrics—settings in which daily life and artful arrangement can coincide. “Woman With a Book” belongs to this restorative turn. It answers the era’s unspoken question—how do we live again?—not with spectacle but with a quiet proposal: we read, we open the shutters, we let light and color re-knit the world.

The Motif of Reading

Matisse has long favored readers, but here the motif is fused with the Nice interior. Reading in this picture is not performance; it is a condition. The figure’s posture—leaning, elbowed, absorbed—turns the act into a shape. The book forms a small white hinge in the lower left quadrant, its angles echoing the slats of the open shutters and the stripes of the robe and bed. In this way, the intellectual act and the decorative logic meet: thought is given a pattern, and pattern is granted meaning through thought.

Composition as Theatre

The composition operates like a stage set with three principal flats. At left, the patterned textile stacked with leaf sprays rises like a decorative proscenium. In the center, the reader occupies a cushioned wicker chair, swallowing into its oval while her robe’s vertical stripes fall like curtains. At right, a vertical of light—door jamb, shutters, and the trapezoid of open air—cuts into the interior and offers a second stage beyond the room. The bed, angled from the lower right corner, adds a diagonal that prevents the composition from hardening into parallel bars. Everything is cropped decisively, so the viewer feels almost inside the room, standing near the bed and looking across toward the reader and the door.

The Architecture of Color

Color builds the space. The room is keyed to warm creams and ochres, with the rosy floor creating a low, soft base. Against this warmth Matisse sets bands of cool blue: the shutters, the bed’s stripes, and a cool note inside the patterned hanging. Between these poles move the robe’s stripes—pink, yellow, blue—braiding the two temperature families. Because the blue repeats at different scales (shutter slats, bed stripes, robe stripes), the eye experiences a pulse rather than an isolated accent. The single small triangle of bright yellow on the door hinge and a few sparks within the wall pattern are enough to keep the interior luminous without glare.

Pattern as Structure

Pattern here is not accessory; it is architecture. The hanging at left supplies a strong, vertical cadence of leaves and stems, a kind of vegetal column that counters the geometric slats of the shutters. The robe translates pattern into softness; its stripes undulate along the body’s folds, humanizing the room’s straight lines. The bed’s stripes, meanwhile, are taut and maritime, their direction echoing the coastline just outside the shutters. Each pattern is scaled to its role—large declarations at the wall, medium rhythms on the furniture, intimate variations on the garment—so that the whole field feels orchestrated rather than busy.

Light and Climate

The painting breathes Mediterranean air. Light sifts through the shutters, not in knife-edge beams but as a general wash that keeps colors tender. Whites are never icy; they absorb surrounding hues—blue along the shutter edges, pink where floor reflects upward, warm cream in the curtains. The exterior is hinted, not described: a palm trunk, a scrap of horizon, a few dark silhouettes. That restraint keeps the climate legible without upsetting the interior’s equilibrium. The sensation is of a room cooled by moving air, a place where reading is possible because light is benevolent.

The Open Door and the Idea of Threshold

Matisse’s windows and doors are never simple apertures; they are metaphors for painting itself: a flat construction that opens onto depth. In “Woman With a Book,” the blue shutters make a grid that acknowledges the picture plane even as they reveal a world beyond. The threshold organizes time as well as space. On one side, the book’s pages mark minutes spent in focused attention; on the other, the outside hints at passing hours and public life. The painting holds both tempos in balance, allowing the viewer to travel between them at will.

The Role of the Bed

The bed’s striped cover, thrust from the lower right, is more than incidental furniture. Its diagonal establishes foreground and anchors the viewer’s position. The stripe’s direction points toward the open door, encouraging an oscillation between the reader and the threshold. The bed also introduces the room’s fourth fabric alongside the robe, hanging, and curtains, completing the quartet that will be the subject of so many Nice interiors: textile conversations that turn domestic space into visual music.

Drawing, Contour, and the Living Edge

The drawing is economical and present. A supple dark contour rides the edge of the robe, defines cheek and jaw, and tightens at the book’s corners. Elsewhere the line loosens, allowing color planes to meet with breath—curtain into wall, floor into bed. The wicker chair is written with ovals and short dashes, enough to make its cradle felt. The exterior figures are dots and commas; their shorthand keeps the outside from upstaging the room. Matisse never fusses with detail he does not need; he trusts the eye to complete what is only suggested, and that trust keeps the surface fresh.

Brushwork and the Evidence of Making

Across the canvas, the paint is handled in quick, responsive strokes. On the shutters, flat passes lay down cool blue broken by narrow slivers of white; on the wall, small taps suggest a stippled, sun-hardened plaster; on the patterned hanging, looser bursts state leaves and stems with joy rather than precision. The robe’s stripes flow with the body, their edges softened to signal fabric. This variety of touch communicates a studio tempo—decisions made in real time, surfaces allowed to remain lively. The painting feels discovered rather than manufactured.

Space: Shallow, Breathable, Modern

Depth is shallow by choice. The floor tilts gently upward; the wall stands close behind the reader; the shutters’ frame pushes against the picture plane. Overlaps—bed before door, chair before wall, curtain before shutters—provide enough recession to anchor the scene. The result is a modern space that preserves the integrity of the surface while offering the sensation of a room one could inhabit. The viewer does not roam into deep perspective; instead, one lingers among relationships: stripe to slat, warm to cool, figure to pattern.

Gesture and Psychology

The figure’s gesture is familiar and humane. Elbow on armrest, fingers supporting temple, eyes lowered: the position we adopt when a sentence asks for our full attention. There is nothing coy or theatrical here; the robe’s generous folds shield the body, and the face, though abbreviated, carries the concentration of thought. Matisse refuses to stage a narrative beyond what the posture offers. The painting’s emotion is the calm of absorption, the dignity of a person at ease with time.

Ornament and Plainness in Balance

Matisse balances ornate and plain with assurance. The lavish hanging would overwhelm a weaker design; here it is answered by large, unpatterned fields—the pale curtains, the solid shutters, the soft wall. The robe’s stripes mediate between the two camps, halfway between ornament and plain. This balance is why the room feels restful rather than crowded: pattern sings, but it sings inside a composed score.

The Book as Formal and Symbolic Device

Formally, the book is a small white flare that stabilizes the left side of the canvas. Its diagonals refresh the field of verticals and horizontals, and its whiteness reappears in curtains, bed linen, and shutter slats, weaving a subtle identity across the painting. Symbolically, the book affirms Matisse’s belief that inner life matters. Even in a room rich with color and air, the mind’s journey through pages is treasured. The title, “Woman With a Book,” underscores that priority: the person and her attention are the subject, with the room as accomplice.

Relations to Matisse’s Other Works of 1919

The canvas converses with the year’s other interiors. Like “Woman by the Window,” it uses a sash of architecture to divide pattern and view. Like “Reading Girl in White and Yellow,” it dignifies a pause of concentration. Like the odalisques and nudes, it relies on shallow space, a few decisive props, and color as structure. But “Woman With a Book” is lighter in climate than the studio nudes and more elastic in its brush than the formal portraits. It stands at the tender end of the Nice spectrum—diaphanous, near-watercolor in feeling, while remaining unmistakably oil.

A Mediterranean Lexicon

Several visual words repeat across the room: shutters, stripes, palms, light cloth, bright floor. Together they write a Mediterranean lexicon—breezy privacy, maritime rhythm, cool interiors against hot exteriors. The blue shutters are the most local note; they carry the specific identity of a coastal apartment and recast it as universal design. Matisse makes place into pattern and, in doing so, lets viewers far from Nice recognize the sensation of a cool room open to summer.

Anticipations of Later Work

The painting foreshadows Matisse’s later cut-out language in its love of silhouette and flat, repeating shapes. The vine-like leaves in the hanging anticipate the paper foliage that will populate the 1940s. The way figure and pattern coexist without hierarchy points toward those late works where human and decorative forms become one chorus. Yet the oil’s soft transitions and wet edges retain something the cut-outs set aside: the experience of light traveling through paint.

The Viewer’s Path

The eye’s route through the picture is choreographed but unforced. Many viewers begin at the book—nearest, brightest—then climb the robe’s stripes to the reader’s face, cross to the open shutters, step out to palm and sky, and return along the bed’s stripes to the room. Each circuit slows; each pass reveals a new small resonance: a yellow hinge, a curlicue of leaf, a blush where floor reflects into fabric. The painting rewards prolonged looking because it was built from patient relations.

Material Presence and the Ethics of Attention

Matisse’s handling honors each substance. The wicker feels woven by virtue of skipping brush; the curtains are translucent because the paint is thin; the floor glows because warm undertones breathe through; the book’s pages are crisp because their outlines are firm. This material truth is aesthetic, but it is also ethical: everything is given its due, from furniture to fabric to sky. The room’s wholeness mirrors the reader’s concentration; attention becomes the painting’s moral center.

Time and the Sense of Duration

Nothing in the picture moves quickly: no wind slamming shutters, no drama across the threshold. Yet time is present everywhere—in the incremental turn of pages, the slow drift of light across floorboards, the suggestion of distant promenaders passing and returning beyond the balcony. The painting holds a slice of duration rather than a frozen instant; it invites the viewer to enter that span and adopt its tempo.

Why the Painting Feels Modern Today

Modernity here is not shock but clarity. The space is shallow and designed; color is used as architecture; pattern is structural; narrative is minimized. These choices continue to feel current because they acknowledge the painting as a made object while honoring lived experience. In an age of distraction, the image models a gracious interior where one can attend—an ideal still worth pursuing.

Conclusion

“Woman With a Book” is one of Matisse’s clearest statements that daily life can carry radiance. With four or five materials—painted cloth, wicker, shutters, paper, and air—he composes an interior that breathes. Bands of blue and warm ochre form the architecture; ornament supplies rhythm; the threshold to the outside keeps the room open to the world; a reader’s absorbed posture gives the scene its human gravity. Nothing is loud, everything participates. The painting invites us to adopt its pace, to let color and pattern order our seeing, and to trust that a quiet morning with a book can be enough to reassemble the soul.