Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

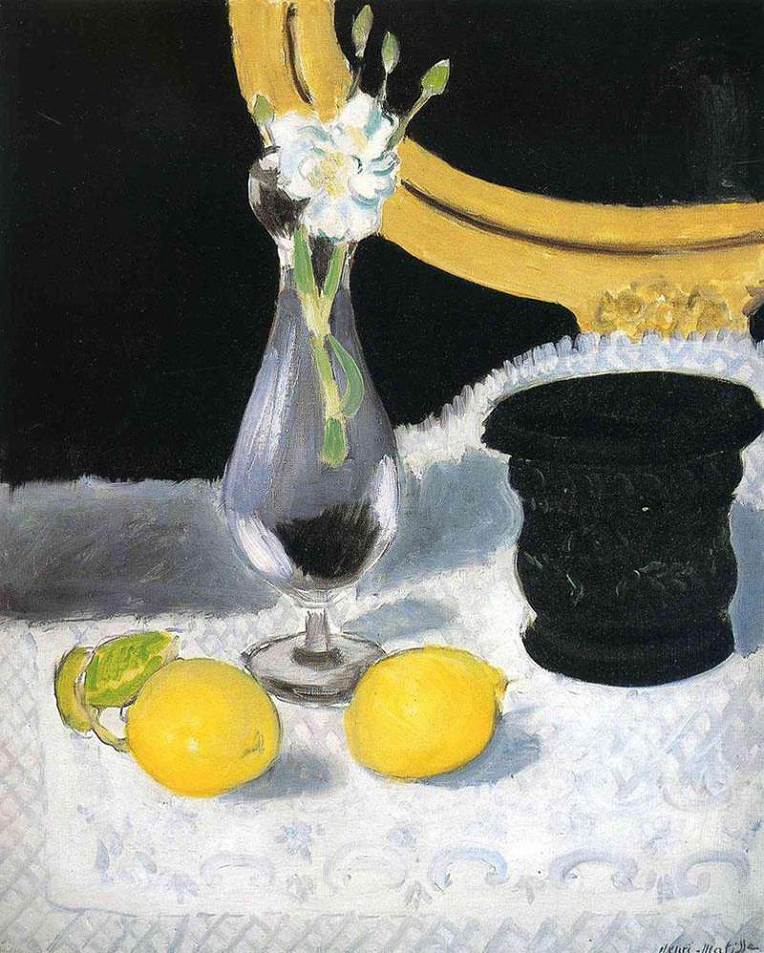

Henri Matisse’s “Still Life with Lemons” (1919) turns a small arrangement on a tabletop into a stage where light, color, and form perform with distilled clarity. Two ripe lemons lie on a damask-white cloth; beside them a glass vase holds white blossoms and buds; to the right sits a heavy, pitch-black vessel; behind, the sweeping arc of a gilded mirror curves across a field of velvety darkness. With very few objects and an even smaller range of hues, Matisse builds an image that feels both intimate and monumental. The painting reads as a lesson in how little a painter needs when relationships are tuned with precision.

Historical Context

The work dates from the beginning of Matisse’s Nice period, just after the First World War. In these years he gravitated to interiors, Mediterranean light, and a quieter palette than the blazing Fauvist canvases of the previous decade. Rather than grand histories or bustling city views, he preferred domestic rituals and studio arrangements—flowers on tables, mirrors, screens, fruits on cloth—subjects that could hold calm after upheaval. “Still Life with Lemons” belongs to that restorative turn. It is not a banquet table; it is a pared-down arrangement in a working room, a modern bodegón in which clarity acts as consolation.

The Set-Up: Objects and Motif

The motif is deceptively simple. Foreground: two lemons, one intact and one accompanied by a twist of green peel. Middle ground: a narrow, stemmed glass vase filled with white flowers and closed buds. Right: a squat, dark vessel, more silhouette than description. Background: a gold frame of a mirror curving like a crescent against deep black, with a faint reflection of the table’s lace edge. The tabletop itself is draped in white cloth whose woven scrolls and border scallops are suggested rather than counted. Everything is ordinary, yet everything is placed so that forms interlock and balance—round against oval, hard against soft, brilliant against absorbed.

Composition as Architecture

Compositionally, the table’s front edge forms a low horizon that anchors the image. Above this, Matisse organizes the objects in a triangular dialogue: the lemons pull the eye left to right across the bottom; the vase rises centrally; the black vessel steadies the right side. The mirror’s golden curve arcs behind them, binding the still life with a unifying sweep. That curve does more than decorate; it prevents the background from feeling like empty void, transforming it into an active counterform that cups the flowers and pushes the dark vessel forward. Cropping is decisive—the mirror is only partly seen, as if the viewer’s attention were focused and the world beyond peripheral.

Color Strategy: Black, White, Yellow, and the Smallest Amount of Green

The palette is a study in restraint. Matisse orchestrates three dominant notes—black, white, and yellow—then spices them with small greens in the stems, buds, and peel. The black is not dead; it is a breathing field that allows the gold of the frame and the lemons’ saturated yellows to flare. The white is not a single tonality but a range from cool gray to warm cream, revealing how the painter believed white is a color with its own harmonies. The yellows vary, too: the lemons carry thick, egg-yolk warmth, while the gilded frame offers a softer, more ochre cast. This triad establishes a high-contrast key that feels both elegant and direct.

Light, Reflection, and the Drama of Surfaces

Light falls from above and slightly to the left, putting clean highlights along the vase’s stem and bowl, and setting small, sharp glints on the lemons’ skins. The glass registers reflections from the dark surroundings; patches of black climb the vessel’s curve and meet crisp stripes of white, so the vase reads as volume through reflection rather than through heavy modeling. The black vessel swallows light; it is almost all shadow, a counter to the bright glass. The mirror’s gilded arc catches illumination as a long band with a faint bloom near its lower edge. By distributing different kinds of light—specular in glass, absorbed in velvet black, diffuse on the cloth—Matisse makes matter palpable without resorting to descriptive fuss.

The Role of Black and Gold

Black and gold together evoke baroque richness, yet here they are stripped to graphic essentials. The black field behind the objects may be the mirror’s reflective depth or a dark backdrop hung in the studio; either way, it functions as a chromatic void that allows forms to pop with sculptural clarity. The gold frame introduces warmth and curvature; it behaves like a halo that ennobles ordinary things. Matisse often spoke of using black as a color, not merely as shadow, and this painting demonstrates the principle: black becomes a positive shape and a stabilizing tone, giving the composition weight and elegance.

The Lemons: Weight, Aroma, and Subtle Variety

The lemons are the painting’s nearest, most tactile presence. One shows a full ellipse with a tiny dimple; the other leans slightly toward the viewer so that the tip catches a crisp, lemon-white glint. The peel twist adds narrative without anecdote: someone touched the fruit, time has moved a few seconds, the air is scented. Matisse captures their substance not with minute pores or hairs but with changes in temperature across the yellow—cooler on the top planes, slightly warmer near the shadows—so that they feel round and heavy. Their placement—spaced but companionable—creates a rhythm that guides the eye toward the vase.

The White Cloth and the Problem of Painting White

Painting a white cloth in daylight is always a test of a painter’s discipline. Matisse answers it by refusing to chase every fold. Broad, cool strokes describe the surface; warm strokes articulate the edges; a few delicate curls across the border hint at damask patterning. He reserves the highest value for small accents—the sparkle at the vase’s base, the cloth’s ruffled edge near the black pot—so the surface retains luminosity without becoming chalky. The white plane, far from neutral, is the painting’s atmosphere; it throws back light into the lemons and receives shadows from the vessels, tying the objects into a single world.

The Vase and the White Blossoms

The glass vase rises with restrained elegance. Its contours are firm, but the interior feels liquid because reflections break into soft patches. The white blossoms—likely carnations or small roses—are laid in with swift, opaque touches that nearly fuse with the tablecloth. Their difference from the cloth comes through temperature: the petals carry a faint blue-violet coolness and sit atop darker, leaf-green marks, while the cloth trends warmer. The buds at the top point upward like little commas, giving the vertical a gentle cadence. There is no botanical insistence; what matters is the sensation of a small burst of life against a sober arrangement.

The Black Vessel as Anchor

At the right the black vessel functions as an anchor. Its shape is simple—a drum with a flared base—but its finish is so matte it reads almost as a silhouette. The absence of interior detail is deliberate; it holds the right side with a single, unwavering mass. This heaviness counterbalances the delicate glass at center and keeps the lemons from floating to the left. The tiny notch of white where cloth meets the vessel’s base is crucial: it separates forms and prevents the dark shape from merging into the background, preserving the painting’s clarity.

Geometry, Curves, and Ellipses

The painting is built from a grammar of curves. Ellipses appear in the lemons, in the vase’s foot, and in the top of the black vessel; arcs sweep through the mirror frame and the ruffled cloth edge. These curves are not mechanically perfect; they are humanly drawn and therefore alive. The repetition of rounded forms creates harmony, while the few straight strokes—the table edge, the vertical of the vase stem—supply counter-rhythm. The eye traces these shapes in loops, discovering that the composition’s calm is the product of underlying geometry.

Brushwork and the Evidence of Making

Matisse’s handling is frank. Thick passages reinforce the lemons’ volume; thinner scumbles in the cloth let the canvas weave breathe; the black background is laid with broad, dark fields that reveal the sweep of the arm. The gold frame’s strokes curve with its path, leaving small ridges that catch the light. These traces of process are not incidental. They remind the viewer that the scene is crafted, not merely copied. The vitality of the painting arises from this visible making—the felt pressure of decisions, the grace of an uncorrected contour, the trust that a single loaded stroke can stand for a petal or a reflection.

Space, Depth, and the Modern Picture Plane

Depth is present but controlled. The tabletop tilts gently, echoing the modern preference for shallow space that keeps the picture close to the surface. The mirror would traditionally open illusionistic recession, but by blacking its interior Matisse denies deep vista and turns it into a flat, curving shape. Overlap and value are enough to cue what little space is needed: the lemons sit forward of the vase; the black vessel partly overlaps the ruffled cloth; the gold frame slips behind both. The painting negotiates a truce between realism and abstraction, giving us palpable objects without surrendering the integrity of the surface.

Dialogue with Tradition

Lemons have a rich history in European still life, from Spanish bodegones to Dutch pronkstilleven. Matisse nods to that tradition while streamlining it into modern clarity. The black-and-gold contrast evokes the elegance of Manet’s black grounds; the quiet authority of the white cloth remembers Chardin’s study of humble things; the structural simplicity and frontality recall Cézanne’s insistence on composition over anecdote. Yet the painting remains unmistakably Matisse: the declarative contour, the elevation of black to a full chromatic partner, and the belief that pattern and object can fuse into a single orchestration all belong to his vocabulary.

Sensory Imagination and Domestic Ritual

Although the objects are few, they summon multiple senses. You can feel the cool weight of the glass, the tack of lemon oil on fingers, the nap of the tablecloth, the matte dryness of the black pot. The arrangement hints at ritual—a vase trimmed for a room, fruit brought to table, a mirror catching the day’s light. The painting honors these small domestic gestures not by narrating them but by treating their forms with dignity. In a year when Europe sought steadiness, such attention to ordinary grace carried moral as well as visual weight.

Rhythm and the Viewer’s Path

The viewing path typically begins at the lemons—those nearest, brightest forms—then climbs the vase to the white blooms, arcs along the gold frame, and settles on the black vessel before returning to the cloth’s ruffle and back across to the fruit. This circuit is musical: bright staccato at the lemons, lyrical ascent through the glass, sustained golden note above, deep bass on the right, soft diminuendo across the cloth. The composition encourages lingering rather than scanning, inviting the viewer to test how each element’s character—gloss, matte, translucence, opacity—contributes to the whole.

Why the Painting Works Today

For contemporary eyes, “Still Life with Lemons” demonstrates how clarity outlasts novelty. Its few colors and measured contrasts feel timeless, its objects familiar, its light believable. In an age of visual excess, the painting’s restraint reads as luxury. It models an attentiveness many viewers crave: a capacity to be satisfied by the relationships of forms at hand. That quality—attention converted into harmony—keeps the image fresh well beyond its historical moment.

Conclusion

“Still Life with Lemons” is a compact masterclass in modern still life. Matisse pares the world to a handful of objects and then builds them into a luminous order. The black ground dignifies the yellow of lemons and gold; the white cloth mediates between brilliance and depth; the glass vase and the dark pot declare opposing kinds of matter; the mirror’s curve binds everything into a single breath. Rather than dazzle with abundance, the painting persuades with balance. In doing so, it reveals the essence of Matisse’s Nice-period promise: that quiet rooms and ordinary things can become sites of radiant equilibrium when looked at with patience and composed with care.