Image source: wikiart.org

First Impressions: The Painter at Work, Not on Display

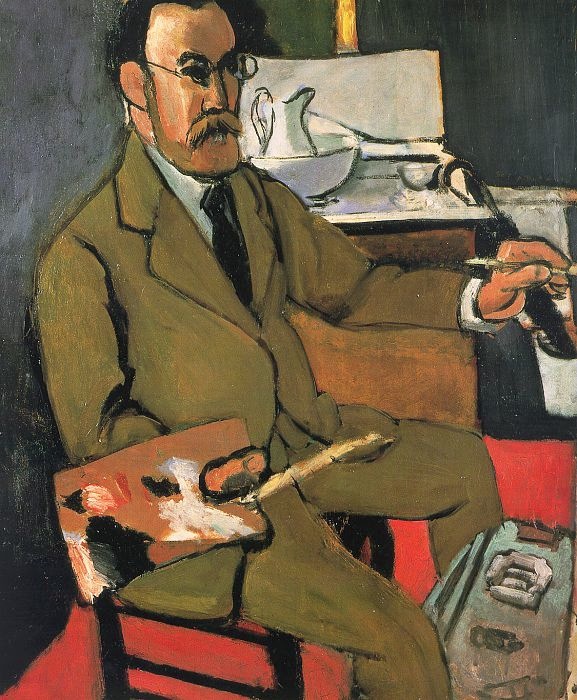

Henri Matisse’s 1918 “Self Portrait” shows the artist seated in a studio, palette in one hand and an extended brush in the other. He wears an olive suit and black tie rather than a smock, the choice immediately positioning painting as professional labor rather than bohemian theater. His head turns just enough to acknowledge us, monocle-like glasses glinting, mustache crisp, expression measured. Behind him, a tabletop still life—white bowl, pitcher, cups—sits before a pale screen. Below and around him, panels of red and black tile the studio like strong chords. The picture reads quickly as a declaration: this is a maker in his workplace, surrounded by the facts of painting—color, tools, subject, and decisive relation.

1918: A Pivot into the Nice Period

The date is crucial. In 1918, Matisse moved into the southern light that would sustain his Nice period. The high voltage of early Fauvism had given way to tuned color and calm architecture; black no longer served merely as outline but as a living anchor inside the chord; space stayed shallow yet inhabitable; and surfaces recorded the pace of making rather than the polish of finish. This self-portrait adopts that grammar and folds biography into form: a mature artist after a decade of experiments, claiming poise without retreating from modernity.

Composition: A Triad of Figure, Tabletop, and Ground

The design balances three interlocking fields. The largest is the seated figure, a strong diagonal from shoulder to knee, composed of broad olive planes edged in energetic darks. Countering him is the tabletop still life behind and to the left, a pale, rectangular stage for curving white ceramics drawn in flexible black. Beneath and to the right spreads an intense red ground that catches the light and keeps the whole image warm. These zones meet in hinges—the wrist extended with brush toward a mixing pot, the left hand gripping a palette that floats above his lap, the chair’s red seat repeating the floor’s hue. Each connection is structural, not anecdotal, and every element is simplified to its work in the composition.

The Pose as a Working Diagram

Matisse chooses a working pose rather than an idealized likeness. The right arm reaches outward, brush held with the delicacy of a conductor’s baton; the left hand’s fingers curl around a palette mottled with quick notes of pink, white, and umber. The torso leans forward a notch, engaging space without theatrics. A triangle of black tie and white collar clarifies the centerline of the body, while the suit’s seams act as drawn lines within color. This posture describes a living circuit—eye to hand to subject and back again—more than it describes psychological intrigue. The result is a portrait of attention.

Palette: Olive, Red, Black, and White in Measured Chords

The canvas turns on a restrained yet potent chord. The suit’s olive green occupies the largest surface, its warmth affected by neighbors: cooler where it presses into black, hotter where it meets the red ground. The floor and chair introduce a saturated, brick red that supplies depth and heat. Black appears in tie, hair, chair rails, tabletop shadow, and the elastic contours of ceramics. White consolidates the still life and flashes in cuffs and collar. Occasional lilac and gray halftones temper transitions. Because the palette is economical, temperature does the expressive work: warm against cool, light against dark, matte against glossy.

Black as a Positive Color

Black is everywhere, not as negation but as pigment with agency. It draws the curve of pitcher and bowl; it stakes the hinge at wrist and elbow; it defines suit lapels with supple strokes; it supplies the painting’s bass line. Against red, black warms; against the pale screen, it cools to ink. Around the face, narrow black notches articulate brow, nostril, mustache, and lip, letting features remain concise without becoming brittle. Treating black as color allows Matisse to hold a light palette without losing structure.

The Face: Likeness Through Economy

Matisse builds the head with a handful of planes. A warm ochre mask turns away from the screen, catching a gentle side light. The eyes are simplified to dark almonds under soft lids; the glasses add a circular accent that breaks the oval and reinforces professional identity. The nose is a quick vertical with a compressed shadow, the mustache a short band that echoes the tie. Nothing is fussed, yet character is unmistakable: alert, skeptical, absorbed. The modeling is temperature-based, not chiaroscuro; cooler notes at temple and jaw turn the form without heavy shadow.

The Studio Still Life as Portrait of Practice

Behind the artist, a tabletop still life serves as self-portrait by proxy. A white bowl, a tall pitcher, a cup, a small cylinder—these are studio props, not domestic tableware. Drawn in black against a pale rectangle, they declare the language Matisse has perfected: volume by contour and temperature instead of layered modeling; whites that are never empty, just slightly warm or cool; curves that carry rhythm as surely as color does. Their presence says what the suit already hints: painting here is not performance but craft honed daily.

The Chair and the Red Planes: Quiet Architecture

The chair is concise but essential. Its red seat binds figure to ground; its dark rails echo the linear energy of the still life; its angle expresses the body’s forward lean. The red floor and lower panels are not descriptive furnishings so much as planes that push the figure into the viewer’s space and stabilize the cooler, paler area behind. Matisse chooses these reds for their architectural role—they act like walls and plinths in a sculpture display—without disguising them with excess detail.

Edges and Joins: How Forms Share Air

Edges are calibrated like seams in a tailored jacket. Along the outer sleeve, a dark, elastic line beds the arm into the background. Where cuff meets wrist, a white notch sharpens the break to give the brush a believable purchase. The palette’s bottom edge softens into the lap so it belongs to both hand and suit. The still-life screen meets the darker wall with a narrow, warm seam that implies distance without a vanishing point. Each join keeps simplified shapes inside the same climate, preventing collage-like separation.

Brushwork and the Time of Making

The surface admits its process. Suit planes are laid in with medium, directional strokes that follow lapel and trouser creases. The red floor is dragged in broader passes, leaving slight ridges that catch the light. The ceramics behind are a calligraphy of quick, decisive lines; the pale fields around them are brushed thin so the weave of the canvas shimmers through. In the palette’s daubs, the pigment sits thicker, an autobiographical reminder that the painting we see was mixed from these very notes. The visible tempo of the brush contributes to the picture’s authority: finish is achieved by relation, not by polish.

Light as Climate Rather than Spotlight

Illumination in this self-portrait behaves like climate. There is no single theatrical beam; rather, a soft, consistent light turns forms by degrees. The suit warms under it; the red panels glow; the pale screen reflects just enough to make the black contours of the still life ring. Because the light is steady, the eye can track the working circuit—artist to subject to palette—without interruption. This quality of light is a hallmark of the Nice period, where atmosphere replaces drama.

Space Kept Close to the Picture Plane

Depth is shallow but convincing. Overlap does most of the work: figure before table, table before screen, screen set against a darker wall. Value and temperature steps refine the effect. The picture remains close to the plane so that color relations dominate, yet space is credible enough to situate the studio. This balance allows Matisse to produce a likeness that is also a designed surface, readable instantly and rewarding at length.

The Suit: Professional Identity and Formal Device

Choosing an olive suit is both biographical and formal. It affirms the artist’s modern professionalism—he is a worker whose labor is intellectual and manual—and gives him a large, unified field for color. The suit’s seams, lapels, and pockets provide inner drawing; the black tie supplies a vertical axis; the white cuffs inject light into the far-right corner near the paint pot. If a smock would have scattered the composition with looseness, the suit consolidates it. This self-presentation aligns with the painting’s structural ambition.

Tools as Extensions of the Body

The palette and brush are not props but extensions of thought. The brush’s arc leads the eye to the paint pot at right, completing the functional triangle that governs studio practice. The palette near the left thigh, smeared with active notes, reflects the canvas’s color logic like a handheld mirror. Even the box on the red floor at lower right—likely a case for supplies—adds a second, quieter triangle with chair leg and brush hand, rooting the gesture of painting into the room’s geometry.

Drawing with Color, Drawing in Color

Matisse fuses drawing and painting. Lines are not preliminary; they are components of color. The black that rings the ceramics, defines lapels, and seats the wrist is at once contour and pigment. Within the suit, thin dark seams act like drawn lines but also shift temperature. In the still life, a single curve can read as a pitcher’s edge and as a dark note in the palette. This dual function keeps the image lively: color carries structure; structure enriches color.

A Self-Portrait of Attention, Not Ego

Many self-portraits stage psychology or theatrical self-invention. Matisse’s 1918 picture resists both. The face is calm; the body is busy. The painter’s role outweighs the personality; the architecture of work outweighs anecdote. By locating identity in the act—hand, brush, subject—Matisse writes a definition of the modern artist as a designer of relations rather than a hero of crisis. That modesty lets the painting remain companionable and fresh.

Dialogues with Tradition, Rephrased in a Modern Tongue

The composition nods to a long tradition of studio self-portraits while revising it. Where earlier pictures might emphasize depth with orthogonals and cast shadows, this one builds space from overlapping planes. Where academic portraits model faces by tiny values, this one relies on temperature shifts and succinct darks. Where conventional still lifes insist on description, Matisse’s ceramics are ideograms, sufficient and musical. Tradition is present as a framework whose grammar has been translated into a modern idiom.

Guided Close Looking: A Circuit Through the Picture

Begin at the right hand and brush; notice the white cuff, the tiny triangular dark under the wrist, and the brush’s tapered line pointing to the paint pot. Slide along the forearm to the triangle of black tie and white collar that locks the torso. Move to the left hand and palette; see the daubs echo the canvas’s chord—whites, reds, blacks—and the palette’s edge soften into the lap. Rise to the face; catch the simple notches that set eyes and mustache, the circular lens that interrupts the cheek, the ear trimmed with a single curve. Drift back to the tabletop still life; let the black curves of pitcher and bowl ring against the pale field; track their echo in the chair rails and suit seams. Drop finally to the red floor, where a box anchors the composition’s bottom corner. Repeat the circuit; the painting reveals itself as a system of linked decisions.

Material Evidence and the Courage to Stop

Small pentimenti enliven the surface: a restated shoulder contour, a second pass on the tie’s edge, a replotted bowl rim, a softened border where screen meets wall. Matisse leaves these traces in place. He halts not at cosmetic smoothness but at relational inevitability, when color, line, and space agree. The viewer senses that inevitability as calm.

Lessons for Looking and Making

The portrait teaches several durable lessons. Limit the palette and let temperature create depth. Use black as a living color to structure light hues. Keep depth near the plane so the image reads quickly and remains inhabitable. Allow tools and surroundings to speak for practice; identity emerges from relation rather than from display. Draw inside color and paint as if drawing; let brushwork carry time and conviction.

Why It Still Feels Contemporary

A century later, the picture’s clarity aligns with current visual habits. Large shapes read on first glance; tuned hues reward sustained viewing; process remains visible and honest. The artist’s self-presentation as a worker resonates with contemporary creative culture, and the studio’s essentials—table, tools, prototypes—could belong to any maker today. The painting feels close because it trusts the essentials of attention.

Conclusion: A Manifesto in Olive and Red

“Self Portrait” condenses Matisse’s 1918 program into one room: a working body in an olive suit, a red ground that radiates, a tabletop grammar of white and black, and a network of edges that seat everything in the same air. The face is economical because the work is expansive; personality is quiet because attention is loud. The painting is neither confession nor costume. It is a modern manifesto written in color, line, and poise—an image of an artist who has become, above all, a composer of relations.