Image source: wikiart.org

First Impressions: Pattern, Sea, and a Poised Human Core

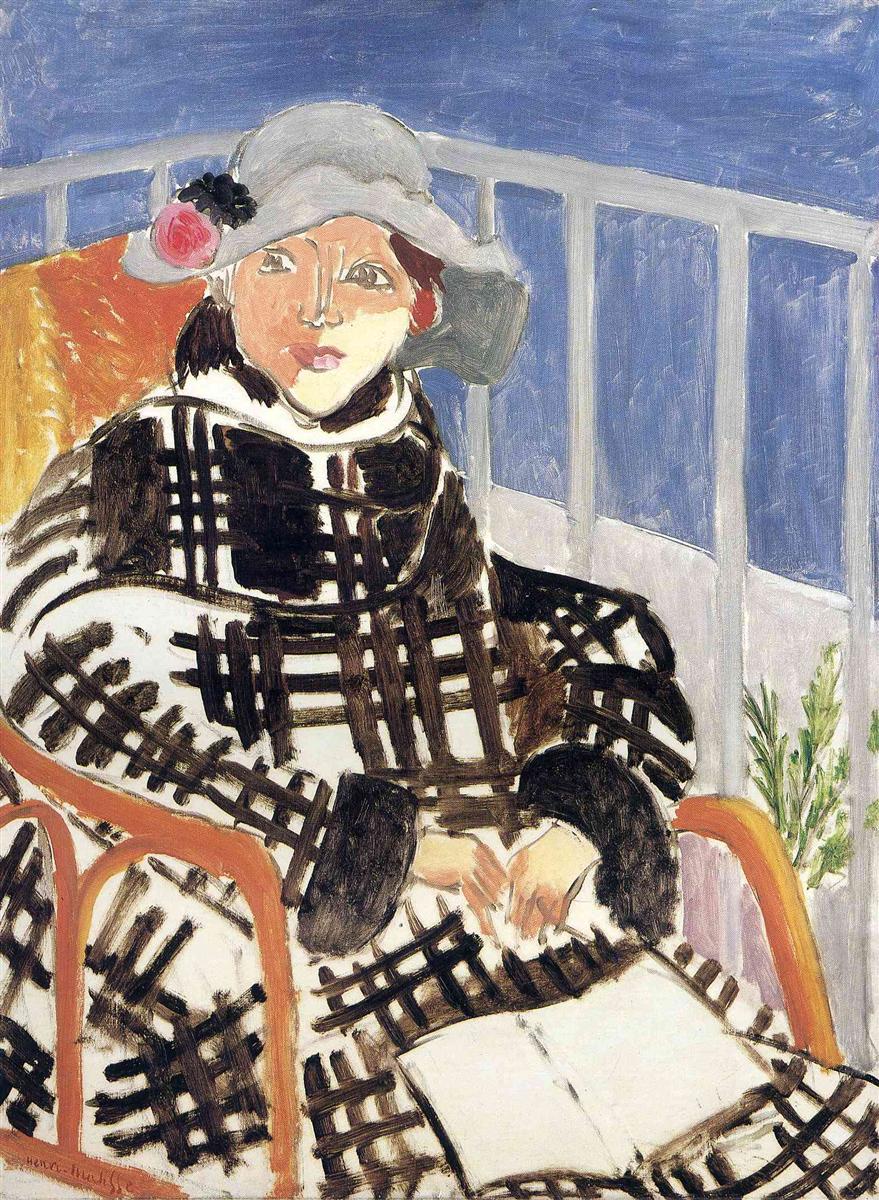

Henri Matisse’s “Mlle Matisse in a Scotch Plaid Coat” presents a young woman seated on a balcony, wrapped in an assertive black-and-white plaid. A gray hat with a pink rosette tilts above a sunlit face, while the pale rail of the balcony curves across a blue expanse of sea. Bentwood chair arms in warm ochre bracket the figure; an orange cushion glows behind her shoulder; an open notebook rests across her lap. The encounter is immediate and calm. Large relations carry the scene: the dark grid of the coat, the cool band of ocean, the lemony arcs of the chair, the living pinks of flesh and flower. Matisse designs a room of air and pattern in which presence arrives quietly and decisively.

1918 and the Emergence of the Nice Grammar

Dated 1918, the canvas belongs to the hinge moment when Matisse developed the key that would define his Nice period. After the carved, high-contrast experiments of the mid-1910s, he shifted to a language of tuned color, shallow yet believable space, and black used as a positive, structural pigment. He favored thresholds—windows and balconies—places where interior calm meets exterior air. This painting is a manifesto of that grammar. It is modern without noise: a measured chord of blue, white, black, ochre, and a few well-placed warms, orchestrated to make pattern serve form and air carry emotion.

Composition Built from Arcs and Grids

The composition is a dance between the balcony’s soft arc and the coat’s grid. The railing sweeps in a long curve behind the sitter; the bentwood chair repeats that curve twice, looping forward like warm parentheses around the body. Against those arcs, the plaid asserts orthogonals. Vertical and horizontal bands cross the coat in varied widths, turning with the body to echo shoulders, chest, and lap. The counterpoint of curve and grid stabilizes the image and gives it legibility from across the room. The figure sits slightly left of center so that the sea can open on the right, allowing light to enter the scene.

The Balcony as Liminal Stage

Balconies in Matisse are never mere furniture; they are sites of passage. Interior and exterior share the frame, and the sitter occupies the threshold. Here the white railing separates and connects at once—its uprights break the blue into panels, letting sea and sky filter in as cool light. A tuft of greenery rises at the far right to acknowledge the living world beyond without stealing attention. The balcony motif replaces narrative with a condition: private poise kept company by open air.

Pattern as Structure, Not Decoration

The “Scotch” plaid is the painting’s protagonist after the sitter herself. Matisse treats pattern as architecture. Thick bars of black paint, sometimes feathered at the edges, sometimes dragged dry, step across white cloth to establish volume and turn. The grid widens at the shoulder, narrows along the forearm, and compresses at the lap to insinuate foreshortening. Smaller cross-hatch notes knit seams and collars. Because the pattern does the form-building, Matisse avoids academic shading, keeping the surfaces bright and legible. The coat becomes both garment and scaffold.

The Face: Warmth Concentrated, Expression Reserved

In a field of cool sea and graphic coat, the head gathers warmth. Cheeks rise in peach and rose; a quick violet shadow lifts the bridge of the nose; a narrow dark at the eyelids sets the eyes in place. The model’s expression is attentive but private—typical of Matisse’s early Nice portraits. He offers no anecdote, no psychological theater, only a person held at a respectful distance, her presence carried by color and relation. The small flower on the hat repeats the facial warmth in a single, tender note.

The Hat and the Role of the Rosette

The broad gray hat mediates between black-and-white coat and blue sea. Its scalloped brim repeats the balcony’s curve; its cool register settles the head into the maritime climate. On the brim, the pink rosette acts like a hinge between face and garment. It repeats the orange of the cushion behind while answering the lips and cheeks at a smaller scale. Because Matisse rarely allows more than one saturated accent per zone, this rose becomes quietly magnetic.

The Chair as Golden Bracket

The bentwood chair is not incidental. Its ochre arms bracket the figure, preventing the plaid from spilling into the sea. Coloristically, this warm yellow rallies the cools and gives the composition a heartbeat. The chair’s geometry also builds rhythm: two parallel arcs, each echoed in the railing and hat, create a loop for the eye to circulate around the sitter and return to the face.

The Open Notebook: Gesture of Leisure and Pace

Across the lap lies an open notebook, almost the only rectangle that does not belong to the plaid. This pale shape slows the lower half of the picture and proposes a narrative of leisure—reading on a balcony, wrapped against sea air—without insisting on story. It also gives the hands a home. Their soft pose and slight asymmetry punctuate the strong geometry and keep the painting humane.

Palette Tuned to the Sea

Matisse’s palette is selective and finely judged. The ocean is downshifted toward a dense, brushed ultramarine that holds together as a single plane. The railing is a cool white tinged with gray so it does not leap from the canvas. The coat’s whites are warm, not sterile; their warmth lets the blacks feel colored rather than absolute. The chair’s ochre and the cushion’s orange are the richest warms; small flesh pinks and the hat’s flower echo them in miniature. The chord is maritime and winter-bright, precise but unstrained.

Black as a Positive Color

No one handles black like Matisse. In this painting, black is a full participant in the color scheme. It constructs the plaid, articulates the neck and collar, strengthens pupils and lashes, and tightens the line at the mouth. Against blue it cools; against chair it warms; against flesh it clarifies and makes pinks glow. Because the black is brushed with visible grain and varied pressure, it records gesture and keeps the surface lively.

Brushwork and the Visibility of Making

The painting wears its making openly. Sea and sky are laid with broad, horizontal drags that leave ridges like ripples. Railing and chair are pulled in longer, steadier strokes that suit wood and paint-worn metal. On the coat, strokes are short, loaded, and directional; you feel the brush skate and catch over weave. In the face and flower, the touches are brisk but small, shifting direction to build planes. Every zone speaks in its own tempo, and those tempos together compose a calm day with air moving through it.

Space Held Close to the Plane

Depth is credible yet shallow. Overlap does the work: chair before coat, coat before railing, railing before sea. Value gives distance its cue: sea slightly lighter toward the horizon, railing consistent and near, coat brightest at the planes that face us. There is no showy perspective; the balcony tilts gently so that the sitter sits in a designed space rather than a plotted stage. This closeness to the plane keeps the painting modern and restful.

Edges and Joins: The Craft of Meeting

Edges are tailored carefully. The hat’s brim meets the blue with a breathed seam that reads as felt against air. The plaid’s black blocks meet white with abrupt edges that declare woven contrast. The chair’s yellow meets the coat’s sleeve with a firmer line to state wood against wool. Along the face, a small halo of lighter paint remains where flesh meets gray hat; the effect is air, not error, and it seats the figure in climate rather than against backdrop.

Rhythm: Rails, Checks, and Curves

The picture’s music flows in three rhythms. The railing provides a steady vertical beat across the horizon. The plaid contributes a syncopated grid that tightens and loosens with the body’s turn. The chair, hat, and balcony edge supply long curves that ride beneath the checks and unify them. As the eye moves from face to coat to sea and back, those rhythms interlock like parts in chamber music. The calm is not static; it is poised.

The Ethics of Reserve

Matisse’s portraits from 1918 are marked by an ethical restraint. The sitter is never mined for narrative; she is seen and respected. Here, the young woman’s hands rest loosely on the notebook, her gaze directed just off to the side. There is no performative flirtation, no coy accessory. The pleasure of looking comes from tuned relations—color, pattern, curve—rather than from psychological staging. That reserve is why the image remains fresh.

Dialogues with Tradition and the Contemporary World

The balcony calls up an Impressionist lineage, yet Matisse pares it to essentials. The plaid suggests modern fashion and urban life, but it has been converted into structure rather than anecdote. The planar treatment of the head nods to Cézanne, while the bold, flat fields and confident contour recall the authority of Japanese prints. All of it resolves into a Matisse sentence: decorative intelligence in the service of human presence.

Sister Works and the Family of 1918 Balconies

Set beside other 1918 balcony portraits, this canvas clarifies Matisse’s priorities. “Young Girl on a Balcony over the Ocean” uses broad shadow stripes and railings to create rhythm; “Mlle Matisse in a Scottish Plaid” heightens the graphic power of the garment; “Marguerite Wearing a Hat” brings the head to the fore with a darker costume and neutral ground. In the present work, the plaid is heavier and more assertive than in many variants, the notebook adds an intimate countershape, and the sea occupies a wider band. Together, these paintings show a consistent vocabulary: thresholds, structural black, visible process, and carefully rationed accents.

Material Evidence and the Courage to Stop

Look closely and you see decisions left visible. A notch of blue reclaimed between hat and railing. A block of plaid reshaped to adjust the shoulder. A seam of white re-drawn at the collar. A soft restatement of the chair’s arc to better cup the figure. Matisse does not polish these away. He stops when relations feel inevitable, not when the surface is cosmetically smooth. The canvas breathes because we can feel those choices.

How to Look: A Guided Circuit

Begin at the pink rosette and watch how it locks the head into the climate of blues and grays. Slip across the scalloped brim into the railing and feel the vertical rhythm. Drop into the ochre arm of the chair and let it carry you to the plaid, where black blocks widen at the shoulder, narrow at the forearm, and press into a dense lattice at the lap. Pause at the hands and the pale rectangle of the open notebook. Then climb the other chair arm back toward the face. Repeating this loop reveals the picture as cadence rather than inventory.

Lessons Embedded in the Painting

For painters and designers, the work is a silent tutorial. Use pattern to build structure, not to decorate. Let black act as living color. Model with temperature rather than heavy shadow. Keep depth near the surface so a scene reads instantly and then deepens. Vary edge quality to seat forms in shared air. Trust a few exact relations—blue band, white rail, yellow chair, plaid grid, warm face—to carry everything.

Why the Painting Still Feels Contemporary

A century on, the image looks surprisingly current. Big shapes read immediately; palette is sophisticated but not loud; process remains visible; the subject’s privacy is intact. The plaid, transmuted into architecture, could be a modern graphic; the balcony’s banded blue could be a color-field painting’s ancestor. Most of all, the painting trusts relation over rhetoric. That trust is the essence of durable modernism.

Conclusion: Pattern, Air, and the Quiet Authority of Presence

“Mlle Matisse in a Scotch Plaid Coat” converts a morning on a balcony into a clear arrangement of forces. The grid of the coat turns into structure; the sea becomes a single, dignified band; the chair brackets the body like warm parentheses; the rosette keeps the head tethered to warmth; the notebook whispers of leisure. With these few elements Matisse composes poise. The picture offers not spectacle but companionship—a human presence held in air by pattern and color, precise enough to feel inevitable and generous enough to be lived with.