Image source: wikiart.org

First Impressions: A Path Cut Through Living Color

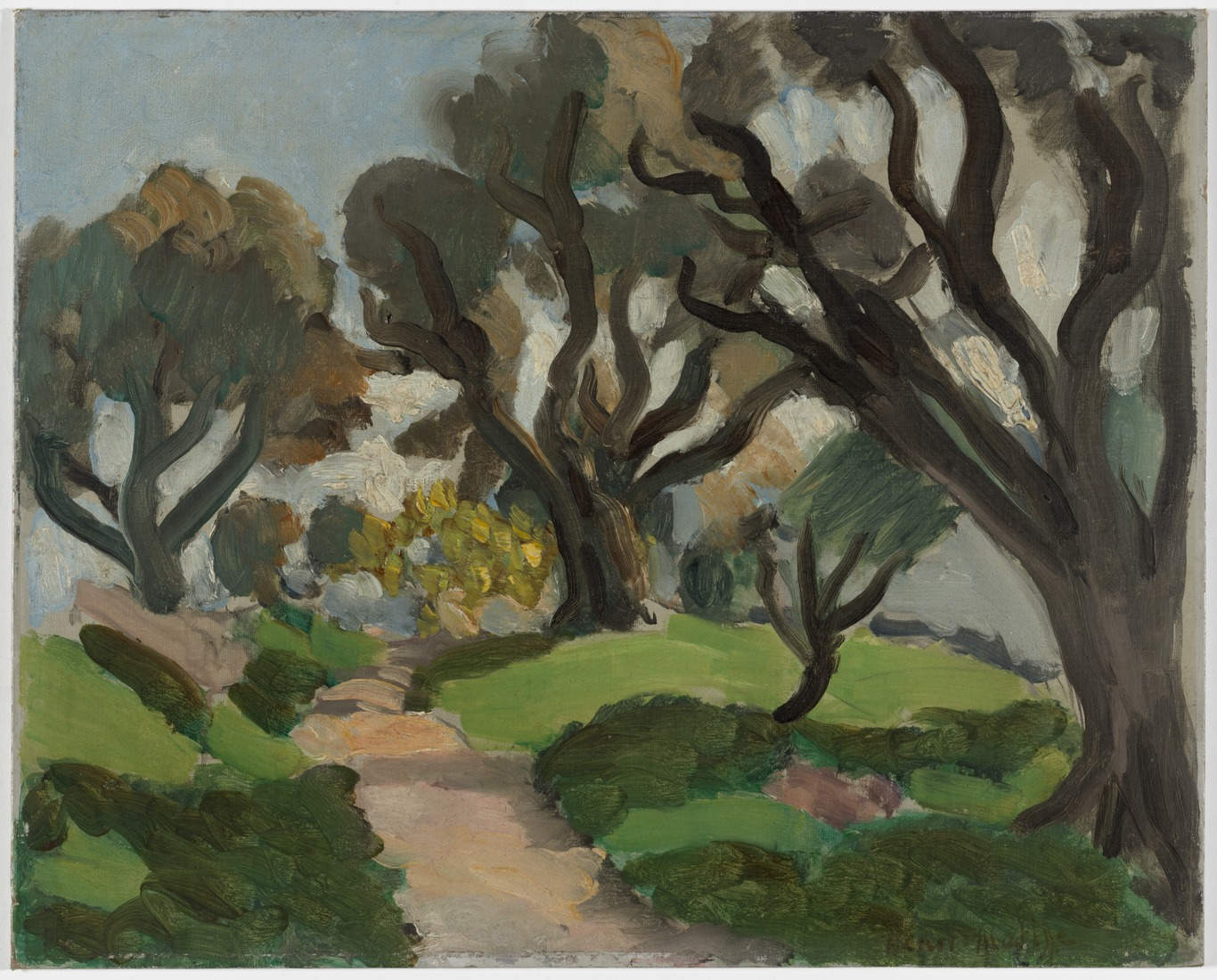

Henri Matisse’s “Landscape” from 1918 greets the eye with a winding footpath leading through a grove of trees toward a light-struck opening. The composition is compact yet expansive: a blue, lightly clouded sky; olive and emerald lawns; dark, serpentlike trunks that arc and twist; scalloped canopies stacked like clouds; and a ribbon of earth that pulls us inward. Nothing is overdescribed. Instead, large relations of color and line carry the scene, and the paint remains visibly alive on the surface. The mood is one of calm energy—the stillness of a midday garden animated by the slow choreography of trees.

1918 and the New Grammar of the Nice Period

This canvas belongs to the pivotal year when Matisse, newly based on the Mediterranean, shifted from the high-contrast, sculptural experiments of the mid-1910s to a tempered, atmospheric language. The Nice years would be defined by measured color, shallow breathable space, and the positive, structural use of black. “Landscape” condenses that vocabulary outdoors. What might have been a catalogue of trees becomes a climate of relations: warm against cool, curve against plane, near darkness against far light. The painting’s serenity is engineered, not accidental; it is the result of deliberate simplification and finely tuned chords.

Composition: A Winding Axis and Counter-Arcs

At the heart of the design is the path, an S-shaped axis that begins in the lower center and slips toward the background. Its bends set the tempo for the rest of the image. Trees to either side lean inward like spectators; their trunks bank in counter-arcs that reinforce the path’s motion while framing the opening beyond. The largest trunk on the right acts as a strong vertical counterweight that prevents the scene from sliding off the canvas. The canopy edges, painted as rounded lobes, mark a second rhythm across the top, a scalloped skyline that keeps the eye circulating between earth and sky.

Space Held Close to the Plane

Depth is convincing yet shallow. Overlap is the primary engine: foreground hedges cross in front of the path; midground trunks step before lighter foliage; sky pushes behind everything. Value shift seals the illusion, with front greens deeper and cooler, distant forms blanched by light. Matisse avoids theatrical perspective lines and hard cast shadows that would force a single hour. Instead, space behaves like a stage: sufficient to wander, intimate enough that the painting remains a designed surface rather than a window.

Trees as Calligraphy

The trees are not botanical portraits; they are strokes of character. Trunks arc in long, elastic lines that thicken and thin with the brush’s pressure. These lines are expressive without noise: their curves describe wind and growth, their dark weight anchors the bright lawn. The canopies above are clusters of rounded, comma-like patches set in slightly different greens and warm grays. This choice suppresses leaf-by-leaf description and turns foliage into mass and rhythm—an orchestration rather than an inventory.

The Path as a Visual Sentence

The path is a pale, warm sentence written across the green page. Its tones shift subtly—peach to dusty rose to gray—so it reads as walked earth scuffed by light. Each bend corresponds to a hinge in the design: a tuft of hedge, a fork between trunks, a glow of yellow leaves in the distance. Because the path narrows softly without disappearing, it holds our attention inside the painting and keeps the eye from slipping out the back. It is both invitation and armature.

Palette: Tempered Greens, Living Blacks, and Quiet Sky

Color does the emotional work with restraint. The sky is a cool, chalky blue, brushed thin so streaks and under-color breathe through. Greens vary from sap to olive to emerald, but none shout; their temperature shifts carry form and light. Darks—almost black—state trunks and the deepest hedges, yet they never deaden; in proximity to blue they cool, against grass they warm, next to the path they sharpen. Neutral earths—taupes and putty grays—hold the bases of trunks and the path’s edges. The chord is Mediterranean without glare: daylight understood as temperature rather than saturation.

Black as a Positive Color

Matisse’s darks are pigments, not voids. Used to draw trunks, score the undersides of canopies, and articulate deep pockets of hedge, black provides the necessary bass notes. Its presence clarifies neighboring hues without outlining them into rigidity. The largest right-hand trunk demonstrates this best: the dark is not flat; it carries warmer and cooler shifts that bend around the bark’s turn. These blacks root the trees in the ground and supply the authority that allows the rest of the palette to remain airy.

Light as Climate, Not Spotlight

There is no single sunbeam, no theatrical shadow. Planes turn by temperature change: a cooler blue is slipped into the sky behind the right tree; warmer greens flare where lawns face us; grayer greens mark recesses under leaves. The bright, buttery yellow at the distant center stands for light entering the grove; around it the world cools as forms move into shade. This approach makes the painting feel more atmospheric than descriptive—a day remembered through sensation.

Brushwork: The Time of Making Left Visible

“Landscape” preserves the pace of its making. The sky is laid in with broad, side-to-side passes that leave fine ridges, like ripples of wind. The hedges are built from overlapping, scalloped strokes whose direction relates to growth, not to photograph. On the path, thinner paint allows the weave of the support to glisten through, giving the ground a granular feel. Matisse avoids cosmetic blending; he lets strokes meet and overlap so that each zone keeps its tempo. The result is a surface that breathes and moves while remaining serene.

Edges and Joins: Where Forms Meet

Edges are tailored with care. The canopy meets the sky with a mix of crisp and feathered boundaries, suggesting leaves dissolving into air. Trunks meet grass with firmer joins, stating the tree’s rootedness. Where the path slides under hedges, a faint, cool shadow is pulled across the warm earth to seat it. Near the center, the yellow blaze is skirted by darker trunks; their edges are softened slightly so light seems to spill into the grove. These craft choices keep simplified shapes from looking pasted on and create the illusion of shared air.

Rhythm: Scallops, Serpents, and Steps

The painting’s music unfolds in three families of rhythm. First, the scalloped canopy edges create a steady beat along the top that echoes in the rounded hedges below. Second, the serpentine trunks bend in counterpoint, their arcs setting longer phrases that guide the eye toward distance. Third, the path introduces steps—each bend a measure—so the viewer’s gaze progresses through the landscape at a humane pace. This rhythmic network is why the painting remains calm even as lines move; order is embedded in motion.

The Opening in the Distance

A small miracle occurs where the path meets the light: a cluster of yellow-green leaves flickers above pale earth, flanked by darker walls of foliage. That opening is the painting’s hinge. It delivers a sense of promise—the garden beyond—without resorting to literal description. It also keeps the composition from closing; the viewer senses air circulating through the grove. By placing the brightest note slightly above center, Matisse sidesteps predictability and keeps the eye returning, each pass discovering new relations around that light.

Comparisons Within the 1918 Landscapes

Compared with “Large Landscape with Trees,” this canvas is more intimate and more animated; trunks here arc like dancers rather than standing as stacked bands. Compared with “Landscape around Nice,” the palette is quieter, the sky chalkier, and the darks more declarative. With “The Stream” and “The Road,” it shares the positive use of black and the reliance on a path or watercourse to organize space. Together these works map a consistent approach: depth kept close to the plane, color tuned by temperature, and shapes simplified until they read with one glance.

Dialogues with Tradition

Cézanne’s lesson—build volume with adjacent planes of color rather than blended shadow—animates the canopies and the faceting of sky; Japanese print sensibility hums in the bold contours and the flat fields that remain flat even as they describe space. Yet Matisse’s voice is unmistakable: decorative intelligence in service of calm, black as architecture, and a faith that a few true relations can carry feeling more honestly than dense description.

The Emotional Climate: Privacy and Ease

The scene is not dramatic; it is companionable. The viewer feels invited to walk, not compelled to hurry. The path is human-scaled; the trees bend as if to shelter, not to threaten. The painting offers that particular kind of rest that comes from clear structure rather than emptiness. If there is narrative, it is the narrative of light moving through leaves, of breath faced toward an opening—an everyday grace.

How to Look: A Guided Circuit

Enter at the lower center where the path begins and feel its warm, granular surface. Let your eye take the first bend left under a dark hedge, then swing back right where a trunk arches overhead. Climb that trunk with your gaze to the canopy, then cross the scalloped skyline to the next tree. Drop back to the path as it narrows and pass between the two central trunks into the yellow opening. Drift outward into the cool blue of the sky and return along the right-hand trunk to the foreground greens. Repeat the circuit; the picture becomes a gentle pulse.

Material Evidence and the Courage to Stop

Look closely and you will see pentimenti—changes left visible. A trunk restated to widen its stance; a canopy enlarged over a cooler underpass; a slice of sky reclaimed between leaves; the path’s edge re-warmed where green had encroached. Matisse does not buff out these decisions. He stops when the relations feel inevitable. That earned inevitability is the painting’s authority: the sense that nothing more is needed.

Lessons for Painters and Designers

“Landscape” is a primer in disciplined economy. Use black as color to anchor airy chords. Model with temperature, not heavy shadow. State foliage as masses with varied edges to avoid leaf-litter fuss. Give viewers a path—not only literally but structurally—so their eyes know how to move. Keep depth near the plane so the image reads at once. Let brush pressure change line weight to record gesture. Trust that rhythm and relation can deliver feeling more directly than description.

Why It Still Feels Contemporary

More than a century on, the canvas looks fresh because it matches modern habits of seeing. Big shapes register immediately; the palette is sophisticated rather than loud; the process is visible and honest; and the space is shallow enough to sit comfortably beside photography and graphic design. Most of all, the painting trusts a small set of exact relations—path to lawn, dark trunk to light sky, warm opening to cool surround—to carry sensation. That trust is as contemporary as any design principle.

Conclusion: A Grove Built from Essentials

“Landscape” condenses the promises of Matisse’s early Nice period into an outdoor scene: serenity through structure, light understood as temperature, and presence delivered by rhythm. The path is an invitation; the trunks are calligraphy; the canopies are music; the opening beyond is a breath. With disciplined means—tempered greens, living blacks, a chalky sky, and visible brushwork—Matisse builds a place that is both real and designed, intimate and open. It is a painting to live with, one that steadies the eye and restores the simple pleasure of moving through trees toward light.