Image source: wikiart.org

Three Figures, One Stage: First Impressions

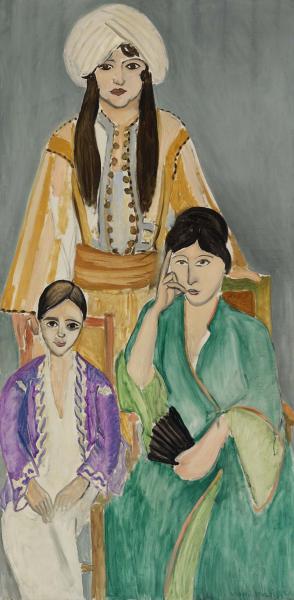

Henri Matisse’s “Three Sisters with Grey Background” (1917) presents a trio of women arranged in a shallow, vertical space with the clarity of a stage set. A tall figure in a turban and saffron-gold robe stands at the rear like a column; before her, two seated companions occupy wooden chairs, one in a cool green gown with a black fan, the other in a white dress and violet jacket edged with rickrack. Behind them there is no interior, no window, no ornament—only an even field of grey that behaves like an idealized wall of air. From the first glance the painting declares its subject: relation. Matisse edits everything that would distract from posture, interval, color harmony, and the quiet chord of three faces held in one room of light.

A Tall Format that Thinks in Stacks and Columns

The canvas is unusually narrow and high, and Matisse exploits this architecture. The standing sister fits the upper third like a keystone; her long robe, sash, and pendant hair turn her body into a structural column. The two seated sisters below form a broad base, their chair rails acting as horizontal beams. This stacked composition produces stability without stiffness. The tall figure’s soft, frontal stance levitates the upper register, while the seated women anchor the lower half with the gravitas of their wooden furniture. Nothing meanders; everything holds.

The Grey Ground as a Sophisticated Stage

The title names the background, and for good reason. The grey is not a neutral absence—it’s the painting’s climate. Matisse lays it in as a broad, breathable field that equalizes the chroma of the garments and skin. Bright colors that might shout in a decorated interior instead become measured voices; the whites and creams of robes and turbans can bloom without glare; blacks become structural accents rather than pits. By refusing descriptive background, Matisse achieves two goals at once: he grants the figures a timeless stage and he affirms painting’s flat surface as a positive actor in the drama.

The Orchestration of Color: Gold, Green, Violet, and White

Palette is the work’s quiet engine. The standing sister’s saffron and apricot robe anchors the warm side of the spectrum; the seated woman to the right carries cool greens trimmed with salmon; the smaller sister to the left wears a high-key violet that bridges warm and cool; whites—turbans, blouses, and the cut edges of garments—act as sources of light. Blacks return as decisive punctuation: hair, eyebrows, the fan, and discrete contours. Because the color scale is limited and the ground is grey, relationships rather than hue-count create feeling. The golden robe supports, the green relaxes, the violet lifts, the whites breathe, the blacks hold.

Drawing with the Brush: Black as Architecture

In 1917 Matisse drew with paint. Brows, lids, nostrils, mouth corners, the crisp edges of cuffs, the seams of jackets, and the carved contours of hair are executed in supple, weighted strokes that thicken and thin like wrought iron. These lines are never a prison for color; they are a scaffolding that bears the composition’s load. At the faces, contours soften to admit air between cheek and background; along garments and chair rails, lines firm up to keep planes legible. The black fan in the green-robed sister’s hand is a small manifesto of this approach: a few essential facets, perfectly placed, turn a flat shape into a handled object with weight.

Costumes and the Charge of Orientalism Reimagined

The turban and embroidered robe on the standing sister—and the near-kaftan cut of the others’ garments—refer to the Orientalist repertory that fascinated Parisian artists. Matisse neither denies nor exploits this charge. Instead he distills the vocabulary into signs that serve the painting’s order: the turban becomes a bright crown that caps the composition; the robe’s golden verticals reinforce the canvas’s tallness; the violet jacket’s ornamental border articulates the smaller figure’s perimeter without fuss. What could have been ethnographic theater becomes studio poetics: familiar garments reframed as devices for light, rhythm, and dignity.

Faces Built from Planes, Not Details

The three faces are spare and structural. Matisse states eyes with calm arcs of lid and a dark, almond iris; the nose is a tight wedge with a simplified bridge; the mouth is compact, its color deepening at the center and cooling at the corners. Cheeks and foreheads turn with temperature shifts rather than deep shadows. This planar approach allows the portraits to read instantly from a distance yet remain tender at arm’s length. Matisse does not pursue likeness by accumulation of small traits; he arrives at presence by placing a few planes and edges exactly where they must be.

Posture as Psychology

Matisse locates temperament in pose rather than theatrical expression. The standing sister—tall, frontal, turbaned—projects guardianship, her hands resting out of frame as if on the chair behind which she stands. The green-robed sister to the viewer’s right reclines slightly in her chair, one elbow propped, a hand touching her temple in a gesture of reflective ease; the fan closed in her lap suggests readiness without restlessness. The smaller figure to the left sits upright, hands folded, gaze direct but calm. Together the trio offers a span from repose to alertness, from contemplation to ceremony, without a hint of strain.

The Chairs as Human Measure

The chairs are more than props; they are tools for scale and interval. Their warm wood sets the flesh’s temperature, their rectangles echo the canvas’s tall frame, and their rails provide precise horizontals that keep the eye from drifting upward unchecked. Matisse keeps their description minimalist—just enough strokes to tell rail from leg, seat from back—because their job is structural, not narrative. In the absence of furniture clutter or wall pattern, these chairs secure the figures in a believable interior and allow the grey ground to stay abstract without feeling empty.

Light as a Democratic Envelope

Illumination is even and generous, the kind that reveals rather than dramatizes. Highlights bloom across the white turban folds, along cheekbones, on the knuckles holding the fan, and at the edges of lapels. Shadows do the minimum necessary: cool under necks, gentle in eye sockets, soft where robes turn away. Nothing here courts chiaroscuro theatrics. This is light designed to keep color honest and structure legible, perfectly aligned with Matisse’s lifelong goal of balance and repose.

The Eye’s Path Through the Painting

The composition proposes a satisfying itinerary. Many viewers begin at the white turban’s flare, descend the golden robe to the sash, step across the chair back to the violet-jacketed sister’s face, then cross diagonally to the green-robed sister’s eyes, pausing on the black fan before returning to the standing figure. Each bend in this loop is punctuated by a clear contrast—white against grey, gold against grey, violet against wood, black against green—so the circuit can repeat indefinitely without fatigue. Looking feels like breathing: steady, measured, refreshing.

Brushwork You Can Feel

Matisse leaves the record of his hand visible. The grey ground moves in long, floating passes that keep the surface alive without insisting on depth. The white turban’s impasto catches actual light, making the garment luminous even in reproduction. The gold robe shows dragged strokes that articulate its vertical fall; the green gown is built from wider, flatter passes that communicate its softer weight. Flesh is a weave of warm and cool strokes that change direction as planes turn. These material facts protect the painting from the slickness of illustration and return it to painting’s central truth: presence made from touch.

Space by Overlap and Compression

The room is shallow by design. The standing figure overlaps the chair back; the seated women overlap their chairs; everything shares the same mild value range so that no figure rockets forward or dissolves backward. This compression keeps attention on relation rather than on the theatrics of depth. The grey ground reads as air, not as a distant wall, and the figures sit within that air like components of a careful chord.

The Discipline of 1917

The year situates the picture at a crucial moment. During World War I Matisse tightened his palette, reintroduced black as a constructive color, and built compositions from clear planes and a few decisive accents. “Three Sisters with Grey Background” exemplifies this wartime clarity. The Fauvist blaze of a decade earlier has been tuned to a restrained spectrum; the Nice period’s patterned interiors have not yet arrived, though their seeds—luxurious costume, a poised tableau—are visible. The painting belongs to a group of 1917 canvases in which Matisse rehearsed how to extract maximum presence from minimal means.

A Dialogue With Portrait Tradition

The bust-length portrait and the family group have long histories in European painting. Matisse engages those traditions but speaks in his own syntax. Where a nineteenth-century painter might have staged the trio in a furnished parlor, he substitutes the abstract discipline of the grey ground. Where academic practice would polish transitions to invisibility, he leaves the brushstroke legible. Where portraits often trade in anecdotal props, he edits down to the essentials of posture, garment, color, and gaze. The painting thus feels classical in its poise and modern in its candor.

Roles Within the Trio

Read as a social constellation, the arrangement suggests roles without enforcing them. The standing sister, crowned and central, reads as guardian or elder; the green-robed sister, hand to temple, could be counselor—thoughtful, inward; the violet-jacketed figure, smallest and most upright, carries the clean vertical of youth. These impressions are produced not by storytelling objects but by intervals and stance. Matisse respects the viewer by offering structure rather than allegory; we infer relationship from poise.

Pattern, Ornament, and Restraint

Ornament is present—buttons down a placket, scalloped edges on the violet jacket, stripes within the gold robe, the closing ribs of a fan—but it never overwhelms. Each pattern performs structural work: the buttons provide a central spine; the rickrack edges of the violet jacket clarify silhouette; the robe’s verticals elongate the standing figure; the fan creates a dark counterweight to the green gown’s broad planes. Matisse’s great talent here is to let decoration sing as harmony rather than as solo.

What the Painting Refuses

Equally eloquent is what Matisse omits: no fluttering draperies, no window or balcony, no vase of flowers to supply narrative. Even jewelry is minimized. By refusing anecdote, he heightens the visibility of design. The result is not austerity but concentration. The painting is generous precisely because it is strict, giving the eye a few precise relationships to savor rather than a buffet of details to consume and forget.

The Cup of Black: A Small Center of Gravity

Among the many gentle tones, the black fan is a critical node. It anchors the right side, echoes the blacks of hair and brows, and keeps the green gown from becoming too expansive. Its triangular facets also set a local geometry that balances the circularity of the turban and the soft rectangles of the chairs. Without the fan the lower right might float; with it, the composition has a palpable center of gravity.

How the Painting Teaches Looking

Spend time with the canvas and it demonstrates a way of seeing: begin with the brightest white, measure the distance to the next strong accent, note the agreement between warm and cool, rest in the even light, and let the brush’s record of touch cue your own breathing. Matisse’s ideal of an art that offers balance and calm becomes an instruction rather than a slogan. The painting does not tell you what to feel; it gives you a room where feeling can settle.

Why “Three Sisters with Grey Background” Endures

The canvas endures because it unites modern frankness and classical poise. It trusts a few color chords and a handful of lines to deliver presence. It treats costume as structure, space as air, and psychology as posture. It is generous to the viewer who wants quiet and exactness, and it rewards the scholar who seeks a hinge work that links Matisse’s wartime discipline to the patterned serenity of his Nice years. Above all, it feels inevitable—as if the trio has always existed in this balance of grey air, white light, and human relation.

A Closing Reflection on Kinship and Clarity

Matisse offers a portrait of kinship that refuses melodrama. Three women share a field of light, each distinct, all consonant. The grey ground holds them the way a key holds notes; the color of their garments provides the music; black writes the score. The longer you look, the more you recognize that the painting’s calm is not emptiness but a highly tuned order. In that order lies the work’s lasting gift: a vision of relation made clear by the simplest, most humane means that painting affords.