Image source: wikiart.org

Three Figures, One Room, and the Architecture of Relation

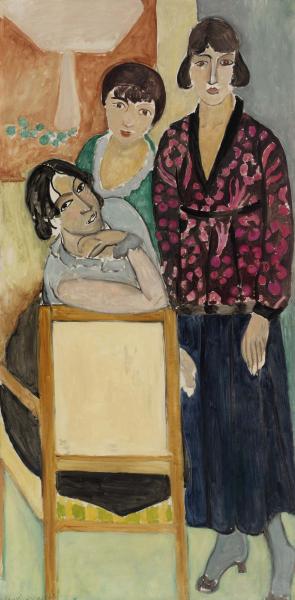

Henri Matisse’s “Three Sisters and The Rose Marble Table” (1917) is a vertical stage where three women share a narrow slice of interior space. The painting compresses a small world into a tall format: a wicker-backed chair turns its back to us like a screen, a patterned jacket blossoms against a column of dark skirt, a lamp and wall panels articulate bands of color, and three heads form a quiet chord of gazes. Even without anecdote or obvious narrative, the image feels charged with relationship. Matisse builds that charge from a handful of clear means—contour, plane, pattern, and interval—so the room becomes a geometry of presence rather than a catalog of objects.

A Tall Composition that Thinks in Columns

The first surprise is the canvas’s stature. The elongated proportion invites a columnar organization: the standing figure at right becomes a vertical beam; the middle sister behind the chair acts as a second, narrower column; the seated figure at left bends an oblique diagonal that prevents rigidity. Between these supports, the flat back of the chair reads as an architectural panel. This scaffold gives the portrait its poise. Nothing leans without support, and yet nothing stiffens, because the heads are staggered in height like musical notes on a staff, animating the static architecture with human rhythm.

The Chair as a Pivotal Prop

Matisse places a chair at the picture’s front as if to assert that furniture can be as expressive as faces. Its pale, blank back forms a neutral rectangle amid the richer fields of clothing and wall, a plane against which arms and shoulders read crisply. The seated woman wraps herself around that support, her body describing a gentle S-curve over the chair’s right edge; the other two figures gather behind it as if behind a balustrade. The chair is not merely a prop; it is the hinge of the composition. It organizes spatial relations, slows the viewer’s approach, and helps convert three separate bodies into one orchestrated unit.

Where the Rose Marble Table Lives in the Picture

The title names an object that may not dominate the frame but echoes throughout it. Matisse had just painted his celebrated “Rose Marble Table,” a pink, octagonal top set like a jewel in a dark ground. Here, that motif is absorbed as logic rather than spectacle. The squared panel of the chair, the angular lamp shade, and the flat zones of wall behave like cousins to that table’s planar authority. The title alerts us to look for stone-like surfaces and marble-cool pauses amid the warm flesh and textile pattern. The result is a disciplined interior in which decorative energy is checked by clear slabs of calm.

A Palette that Balances Bloom and Breath

Color in 1917 Matisse is measured. He restrains the Fauvist blaze and lets a few chords carry the room. Warm blushes of skin, a pearly gray-blue blouse, the soft green halo behind the middle sister, a rosy-mauve jacket spangled with darker blossoms, and a slate skirt sink into a climate set by pale walls and a cream lamp. Nothing shouts. The jacket’s pink is the painting’s most theatrical note, but it’s tempered by the black collar and belt that give it structure. The greens cool the upper center, keeping the skin tones fresh; the pitcher of black hair and bands of contour organize the whole. The harmony suggests daylight diffused by fabric shades—no harsh sun, only a steady, breathable atmosphere.

Black Contour as the Picture’s Architecture

Matisse draws with a loaded brush. Brows, lids, nostrils, lip lines, hair silhouettes, the jacket’s lapels, the chair’s rails, and the skirt’s pleats are stated with strokes that thicken and thin as needed. These lines do not merely fence in color; they bear weight like ironwork. Around the faces, contour softens at temples and cheeks so air can pass; along garments and furniture, it firms up to keep planes true. This language of edges allows flat color fields to act as volume without deep modeling. The black is not a denial of light but a tool that clarifies relation.

Three Temperaments, Three Postures

Matisse locates psychology in pose rather than in overt expression. The seated sister leans her head on crossed arms over the chair’s top, her gaze directed slightly outward and up, a posture of languid curiosity. The middle sister stands close behind, shoulders squared, mouth relaxed, eyes steady; her green neckline and white blouse set a calm center. The rightmost sister, in the patterned jacket, faces directly forward with composed assurance, one hand visible against the dark skirt, the other partly occluded by the chair. Together they describe a spectrum of alertness—from recline to quiet watchfulness to poised authority—without theatrical gesture. The grouping suggests intimacy and difference at once.

The Lamp, the Walls, and the Discipline of Planes

The interior’s background is a grammar of simple shapes. A lamp with a white shade anchors the top left like a glowing trapezoid; a small chain of turquoise forms, perhaps flowers or glass drops, ornaments the space beneath it; adjacent wall panels—beige, salmon, gray-green—stack in blocks that echo the canvas’s tallness. These planes do more than set a scene. They declare the painting’s flatness and keep decorative energy in check. Pattern and person sit within a room that respects basics: rectangle, column, band, slab. The world feels designed, not cluttered.

Textiles that Speak Without Overpowering

Clothing in this painting is character. The right figure’s jacket carries a rose-and-plum motif scattered like petals across a garden at dusk; its black collar and sash keep the blossoms corralled. The middle sister’s green edging and white chemise give her the calm of a cool spring; the seated figure’s gray-blue blouse gathers into short sleeves that reveal the geometry of her arms. Even as pattern and ruffle enter, Matisse’s economy remains. He states essential folds with a few directional strokes and refuses to braid the surface with needless detail. Textile remains text, not chatter.

Light as an Even Envelope

Illumination arrives without theatrics. There are no hard cast shadows, only soft coolings and warmings that clarify planes. Highlights bloom along the lamp’s edge, on the jacket’s lapel, at the cheekbones, and over the chair rails. Shadows are gentle; they tell us where forms turn without dramatizing the turn. This broad, democratic light fulfills Matisse’s ideal of a painting that offers rest. It keeps the eyes moving comfortably through the picture for a long time.

The Eye’s Path Through the Picture

Matisse choreographs a thoughtful itinerary. The gaze often begins at the seated sister’s tilted head, crosses the chair back to the central figure’s face, and then climbs to the right figure’s eyes, where the floral jacket arrests and holds attention. From there the eye falls along the dark skirt, returns to the pale chair rails, glances at the lamp’s trapezoid, and settles again on the trio of faces. Each turn is marked by clean value and color contrasts—pink against black, cream against gray-green, flesh against pale wall—so the circuit remains pleasurable and clear.

The Vertical Format as Emotional Measure

Why such a tall canvas for a domestic scene? The answer is emotional grammar. The format pushes the figures to stack and overlap, increasing nearness and complicating hierarchy. The rightmost sister’s full-length presence grants her authority; the centrally placed, half-length figure mediates; the seated figure’s diagonal relaxes the frame. Together their arrangement delivers the psychological impression of a family constellation—roles distributed by position, not declared by expression.

Brushwork that Records Touch

Look closely and the surface tells stories about its making. The lamp’s shade is laid with soft, even strokes that keep its whiteness matte. The jacket’s blossoms are quick, rounded stamps of darker paint, some pulled by a dragging bristle, which adds life to the pattern. Flesh turns with broader, flatter passes that change direction as cheeks and forearms curve. The chair’s wood reveals longer sweeps that resist the surrounding fabrics’ small movements. These choices keep material truth visible; the painting honors its subject with the frankness of its craft.

1917: Discipline After the Blaze

This canvas sits at a hinge in Matisse’s career. In 1917, during the war years, he had stepped back from the high-voltage primaries of Fauvism and reintroduced black as a structural color. Compositions grew more architectural. Figures took their place in interiors defined by clear planes and carefully rationed decoration. At the same time, the seeds of the Nice period—interest in patterned garments, serene domestic spaces, languorous poses—were germinating. “Three Sisters and The Rose Marble Table” embodies both sides of the hinge: wartime clarity and the opening bloom of decorative repose.

Between Group Portrait and Interior Still Life

The picture occupies a rare middle ground between portrait and still life. The three figures carry the nominal subject, yet the chair panel, lamp, and wall behave like a set of objects carefully arranged. Matisse treats people as elements in a design whose balance matters as much as likeness. The result avoids the pitfalls of anecdote: there is no story to read in props, no moral to infer from posture. Instead, the painting proposes that relation itself—spatial, chromatic, psychological—is the real content.

The Ethics of Reduction

A recurring pleasure in this work is what Matisse refuses to include. Hands are simplified to the point of emblem; hair is treated as succinct masses, not strands; the lamp is a shape first, an object second. Reduction is not denial; it is respect for essentials. The room holds exactly enough for the figures to be felt as presences. The painting trusts the viewer’s experience to complete what is only suggested, and that trust lends it a rare dignity.

A Reading of the Sisters’ Relationship

The trio’s alignment suggests companionship without hierarchy. The right figure’s full stance could dominate, but her downturned hands and calm face temper authority. The middle figure stands closest to the lamp and the cool green field; her role feels mediating, cooling, kind. The seated figure’s diagonal across the chair gives the group its warmth and human ease; her tilt proposes conversation, the beginning of a smile hovering in the corner of the mouth. The painting thus modulates from repose to curiosity to presence, like a chord resolving slowly into harmony.

The Rose Marble Table as an Idea About Order

Even if the titular table is not asserted as an object in the frame, its spirit governs the room. In Matisse’s paintings of 1917 the rose marble slab stands for measured design—an octagon of stillness amid foliage, fabric, and flesh. Here the chair-back’s rectangle, the lamp’s trapezoid, and the wall’s color panels act as equivalent planes of order. Their calm prevents the floral jacket from overwhelming the group and keeps the viewer’s attention where it belongs: on the constellation of faces.

Why This Painting Still Feels Modern

The canvas remains fresh because it solves complex problems with clear means. It stages three people in a small space without turning theatrical. It lets pattern bloom while preserving architectural calm. It uses black to support rather than to scold color. It builds psychological presence from pose and interval rather than from acted expression. Standing before it, one feels a quiet confidence—of a painter who knows exactly how much to do and when to stop.

A Closing Reflection on Balance and Kinship

“Three Sisters and The Rose Marble Table” offers an art of balance that does not erase individuality. The women hold the room together by simply being themselves within a design that honors them. When your eye finishes its circuit—from the chair’s panel to the faces, to the jacket’s petals, to the lamp’s white, and back—it settles into a pace that feels like conversation. In that pace lies the painting’s lasting gift: kinship made visible by structure, and serenity made possible by a few exact relations of color and line.