Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

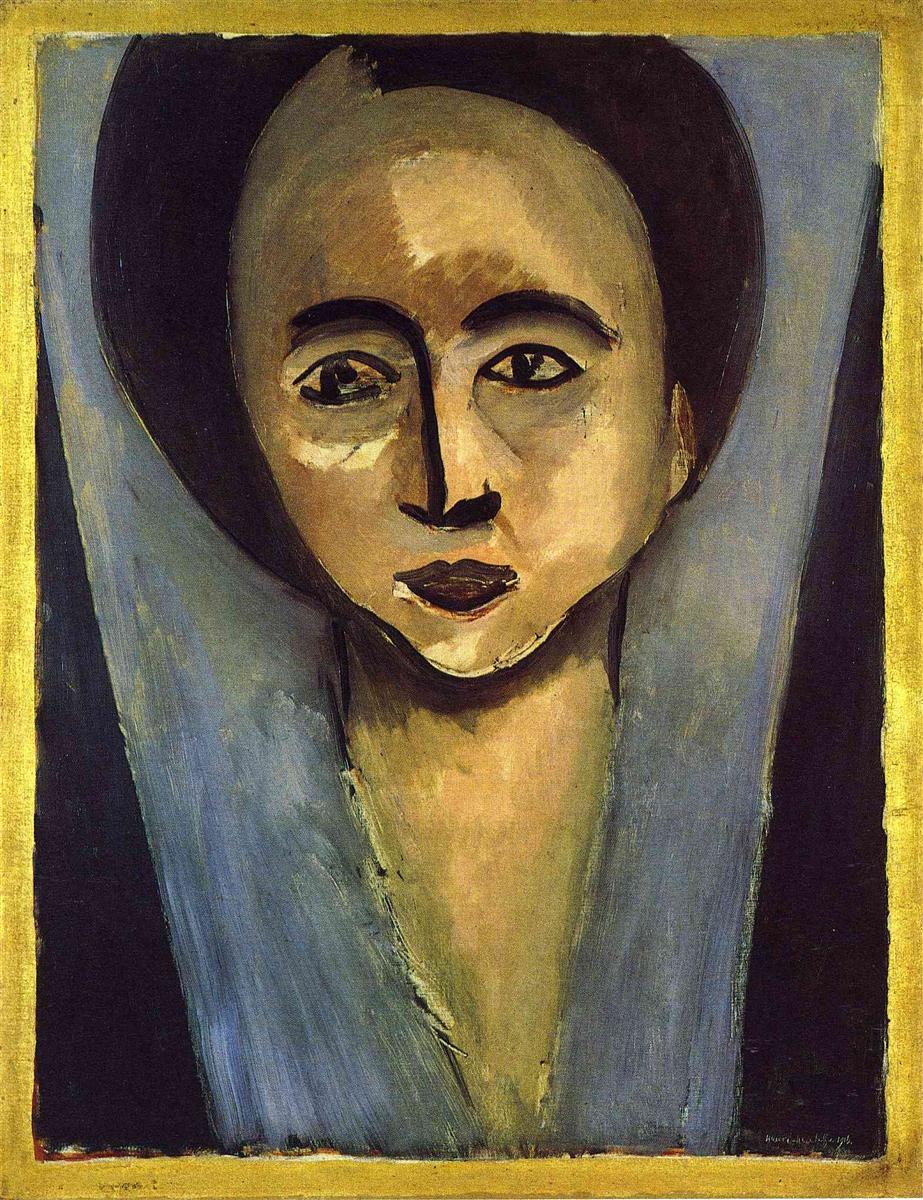

Henri Matisse’s “Portrait of Sarah Stein” (1916) is a compact, frontal image that transforms a beloved patron into a modern icon. A luminous face, modeled in warm ochres and grays, floats within a dark oval of hair or hat. A cool, blue-gray garment opens in a V below the chin, channeling light downward while the surrounding blacks pull the head forward. Framing everything is a painted gold border that reads like a halo stretched to the rectangle’s edges. With a restricted palette and a handful of emphatic contours, Matisse achieves an image of quiet authority and psychological nearness, a summation of his wartime search for clarity and order.

Historical Context and the Stein Connection

The years 1914–1917 marked a decisive shift in Matisse’s art. After the blazing chroma of Fauvism, he pared his language to large planes, stronger structure, and sober color. Paris, shadowed by war, heightened this move toward concentration. Among the few sitters granted the privilege of his undivided attention were Michael and Sarah Stein, early collectors who had supported Matisse when critical opinion was hostile. The portrait of Sarah is more than a likeness; it is a recognition of loyalty. Matisse repays patronage not with surface luxury but with a poised, distilled image that honors her presence in the evolution of his art.

First Impressions and Visual Architecture

At first glance the picture organizes into three interlocking shapes: an elongated, light face; a dark, nearly circular surround of hair or hat; and a triangular V of blue-gray garment that points toward the chest. These three shapes nest inside a golden border that reads as a secondary frame, turning the canvas into a modern devotional panel. The head is centered and upright. The eyes align just under the painting’s midline; the mouth and chin anchor the vertical axis. There is almost no spatial anecdote—no furniture, no window—so the viewer’s attention remains fixed on the face as a realm of decision.

The Painted Frame and Iconic Overtones

Matisse’s painted gold border is not decoration alone. It functions like the gilded ground of Byzantine icons, where gold is not a color of sunlight but a sign of presence. Here it isolates Sarah Stein from external space and declares the portrait a self-sufficient object. The border also stabilizes the color system: its warm ochre sets the key and allows the cooler garment and black surround to register cleanly. This device converts the portrait into a hybrid form—both intimate likeness and portable altar to modern painting’s essentials.

Palette, Temperatures, and the Ethics of Restraint

The palette is spare but eloquent: warm ochres for skin and frame, blue-grays for the garment, dense browns and blacks for hair and surround. Within that limited range, shifts of temperature do the expressive work. A faint rose note warms the cheek; a cooler gray carves the temple; a smoky brown weights the upper lip and nostrils; charcoal black sharpens brow ridges and the bridge of the nose. Because saturation is held in check, these small temperature toggles feel consequential. They provide breath without theatrical light and confer dignity without sentimentality.

Drawing and the Authority of Contour

The portrait’s grammar is contour. A supple black line arcs over the brows, runs down the nose’s bridge, cups the nostrils, and closes the lips with a crisp, small lozenge. Around the face, line alternates between firm and broken, allowing flesh to blend with shadow where needed. The garment’s V is stated with wide, confident strokes that taper as they descend, creating a funnel of light. This economy of drawing achieves what endless hatching cannot: structural clarity with minimal means.

Planes Instead of Modeling

Rather than traditional chiaroscuro, Matisse builds the head from interlocking planes. The forehead is a broad, warm field broken by a cooler wedge at the right temple. Each cheek turns with a single, decisive shift in value. The nose is carved from two adjacent planes that meet in a vertical seam of dark. The lips are simple facets stacked above the chin’s softer triangle. This planar construction recalls the lessons Matisse drew from Cézanne while preserving his own fluency and warmth.

The Dark Surround: Hair, Hat, Halo

Encircling the skull is a dense brown-black that reads alternately as hair and as a soft, round hat. Matisse refuses to specify. That refusal lets the dark mass function abstractly as a stabilizing counterform. It pushes the face forward, intensifies the whites of the eyes, and completes the icon-like oval within the gold border. The ambiguity is purposeful: it keeps the picture poised between portrait and emblem.

Eyes, Gaze, and Psychological Nearness

Sarah’s eyes are the portrait’s quiet fulcrum. They are not meticulously detailed; the irises are laid with dark ovals, their lights picked out with tiny, angled strokes. Yet the gaze is direct, steady, and unflinching. The slightly asymmetrical lids and the modest compression of the mouth forestall idealization. We sense watchfulness, intelligence, and composure—qualities consistent with a woman who collected daring work and stood by an artist through difficult years. Psychology here is delivered through design rather than anecdote.

The Blue-Gray V and the Channeling of Light

The garment’s triangular opening funnels light toward the center and prolongs the face’s vertical thrust. Its color is cool but not sterile—built from scumbled strokes that leave the canvas breathing. Where the V nears the neck, a darker seam suggests fold and depth without literal hems or stitchery. The V also functions metaphorically: it is an opening that invites attention inward, aligning with the portrait’s overall movement from border to surround to face.

Surface, Brushwork, and Evidence of Decision

The surface retains the record of its making. In the background, broad strokes run diagonally and vertically, their edges visible like currents under a thin glaze. The forehead holds both smooth passes and small, skidding touches where the brush skipped over tooth. Along the jaw, a faint halo indicates that Matisse adjusted the contour late in the process. These pentimenti and changes of pressure keep the surface active and human. The picture’s calm is not mechanical; it is achieved.

Comparative Context within the 1916 Portraits

Placed beside “Portrait of Michael Stein,” this canvas feels even more iconic. Where Michael’s suit and tie form a dark triangle beneath the face, Sarah’s garment opens to a pale wedge that amplifies luminosity. Compared with the lush textiles of the Laurette series, the Sarah portrait is ascetic, using only the essentials to establish presence. The family of forms—painted frame, oval surround, planar face—connects the picture to Matisse’s broader wartime method while the tenderness of the eyes distinguishes it within that method.

Light, Value, and Redistributed Illumination

Matisse does not stage a single directional light. Instead he redistributes value to articulate structure. The forehead receives the highest lights, balanced by medium tones around the cheeks and a dark cap of hair. The deepest darks collect in brows, nostrils, and the small interval between the lips. The overall value range is controlled, which allows tiny highlights—at the inner corners of the eyes or on the lower lip—to exert real influence. The result is illumination from within rather than from an external lamp.

The Role of Negative Space

The dark wedges flanking the garment and the black surround above serve as active negative space. They relieve the face and garment of any background clutter and create pressure that keeps the head taut within the frame. The negative shapes are not voids; they are sculpted counters, as crucial to the portrait’s rhythm as the positive forms. Their weight gives the face an almost architectural stability.

Modernity, Tradition, and the Icon

Matisse often bridged tradition and modernity by translating historical formats into the language of color planes and contour. “Portrait of Sarah Stein” is an exemplary case. The painted gold frame and frontal pose recall sacred portrait conventions. Yet everything is modernized: gold is pigment, not metal leaf; the face is built from planes, not glazes; the garment is a single, abstract V. The result honors the sitter as a figure of personal significance while offering a manifesto for painting stripped to essentials.

How to Look

The portrait rewards a pattern of looking that alternates between distance and proximity. From across the room, feel the stability of the gold border, the dark oval, and the pale face locked into a clear geometry. Move close to see how very little is used to make a mouth or an eyelid. Trace the contour where it tightens at the nose and loosens at the jaw. Notice the soft scumble that cools the right temple and the small warm patch that heats the left cheek. Step back again so that the separate moves cohere into a single, thoughtful presence.

Meaning and Legacy

Because it is so reduced, the painting teaches by example. It shows that personality can survive—and even thrive—within a rigorous system of planes, lines, and limited hues. It demonstrates how a painted frame can become a compositional device, not merely an outer accessory. It models a way to be modern without forfeiting reverence or warmth. For viewers and painters alike, “Portrait of Sarah Stein” remains a lesson in how little is needed when every choice is exact.

Conclusion

“Portrait of Sarah Stein” is both thank-you and thesis. It honors a crucial supporter with an image that is steady, luminous, and humane, and it clarifies Matisse’s wartime conviction that economy could yield depth. The golden border sets the terms, the dark surround steadies the head, the blue-gray V invites us inward, and within that architecture a living face meets our gaze. The canvas holds its ground as a modern icon, proof that restraint, when guided by feeling and intelligence, can be radiant.