Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

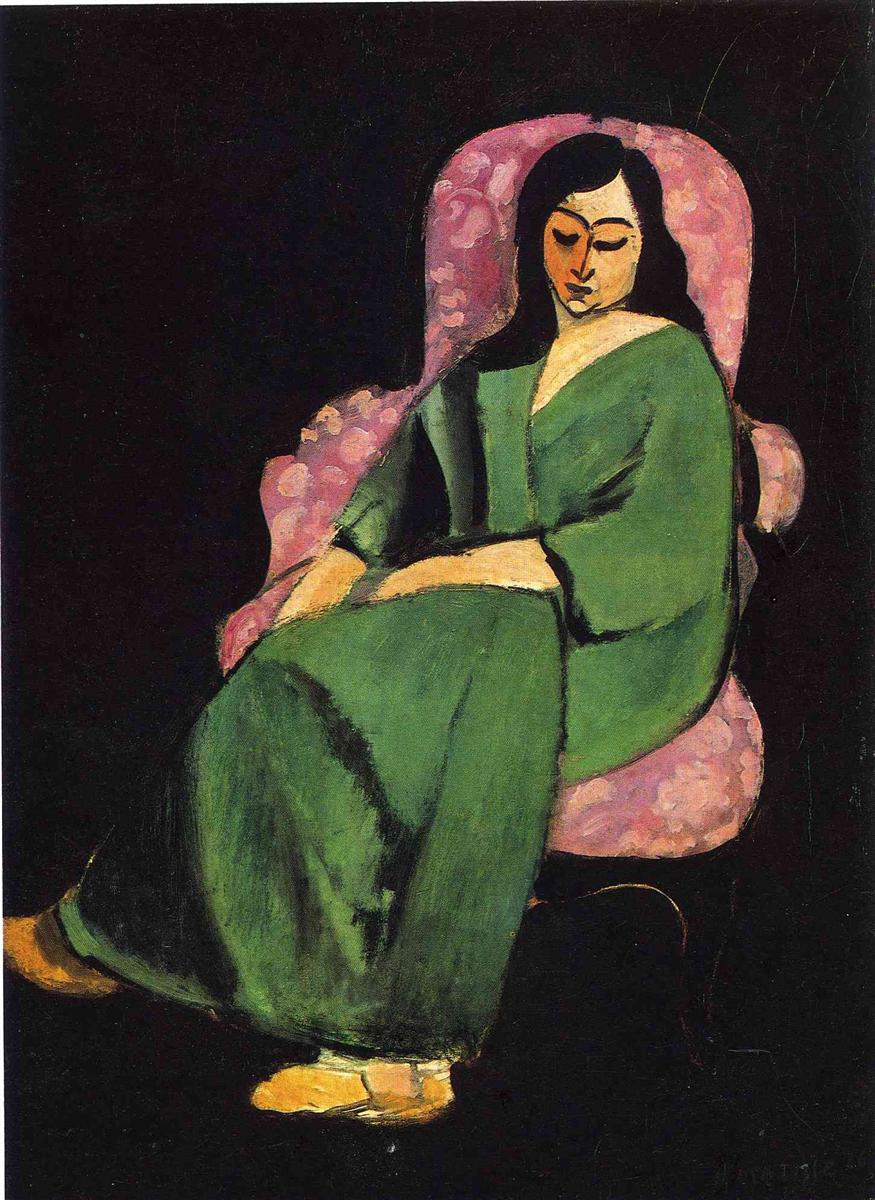

Henri Matisse’s “Lorette in a Green Robe against a Black Background” (1916) is a masterclass in how color, silhouette, and contour can carry the full emotional weight of a portrait. A young woman reclines into a pink upholstered chair, its floral pattern barely glowing against a field of velvety black. Her robe is a saturated green that falls in long planes over her body, broken only by quick seams of darker pigment and the pale architecture of her neck and hands. The face is simplified and masklike but unmistakably alert, turned slightly downward as if suspended between waking and reverie. The painting is spare yet sumptuous, ascetic in palette yet generous in feeling, and it stands among the most resonant canvases from Matisse’s wartime period.

Historical Context and the Laurette Cycle

The model known as Laurette occupied Matisse’s studio and imagination throughout 1916–1917. He painted her in turbans and patterned dresses, in interiors and near windows, testing how few means were needed to find character. The years 1914–1917 were a crucible for him: the exuberant Fauvism of the previous decade cooled into a language of big planes, hard contours, and carefully rationed color. “Lorette in a Green Robe against a Black Background” concentrates many of these discoveries. It retains the decorative impulse of his Moroccan paintings, but exchanges travel’s daylight for the controlled climate of the studio, where black ground, pink chair, and green robe can be tuned like the stops of an organ.

First Impressions and Visual Structure

From across the room the picture reads as three interlocking shapes: a dark emerald triangle describing the robe, a pink, cloudlike form indicating the chair, and a wide midnight field that swallows the rest of the room. These large forms lock together to form a stable, almost heraldic arrangement. The body tilts gently from upper right to lower left, and that diagonal is caught by the chair’s sympathetic curve and the floor-length fall of fabric. The feet, rendered in warm ocher, create a small counterweight that keeps the figure from floating. The face, small relative to the robe, becomes a concentrated focal point precisely because everything around it is simplified.

The Role of the Black Background

The title names the black background, and for good reason. Matisse uses black not as a shadowed corner but as a positive, constructive color. It operates like velvet, absorbing light so that the green robe and pink chair flare forward. Black also collapses unnecessary depth, turning the portrait into a frieze where figure and support are on the same plane. In this controlled darkness, edges matter; every contour becomes an event. The black is not flat—its brushwork reveals soft swirls and thin passages—yet it behaves as a unified field, a theater curtain drawn back just enough to let the central forms perform.

Color Architecture: Green, Pink, and Ocher

Matisse orchestrates the palette with three principal notes. The green robe carries the dominant theme. It is a deep, cool green modulated by darker seams and lighter, chalky passages where the cloth turns. The pink chair reads as the robe’s complement and as a quiet echo of flesh. It is patterned but not fussy, its floral blotches flickering like soft lights within the larger mass. The ocher shoes and the buff tones of hands and face add warmth at the extremities, preventing the canvas from becoming too polarized between cool green and hot pink. The palette is limited, but the intervals between these colors are exquisitely calculated so that the eye moves through them like chords.

Drawing and the Authority of Contour

The painting’s drawing is as decisive as its color. A supple black contour runs along the robe’s hem and sleeve, around the curve of the chair, and across the line of the jaw. The line swells or thins as needed, thickening where Matisse wants weight and leaning away where he wants air. Facial features are rendered with sparing, angular strokes—arched brow, quick nose, compressed lips—that suggest both the particular Laurette and a more universal mask. The contour does not merely describe; it organizes the picture, setting a rhythm that guides the eye from shoulder to wrist to ankle in one continuous phrase.

Pose, Gesture, and Character

Laurette sits deep in the chair, one arm resting and one hand descending toward the lap, her head inclined with the economy of someone who keeps her thoughts to herself. The robe’s V neckline exposes a pale triangle that answers the chair’s pink cushion and directs attention to the face. Nothing is theatrical; the pose is a distilled anecdote of rest. That restraint gives the portrait its gravity. Laurette’s downward glance evokes alertness rather than sleep. The hands, simplified into pale, structural shapes at the robe’s edges, extend her presence into the surrounding space without breaking the quiet.

The Green Robe as Architecture

Matisse treats the robe as both clothing and building. Large planes of green behave like walls; their seams and folds function as shallow pilasters that articulate volume without fussy modeling. Within the robe, he introduces temperature shifts—cool viridian beside warmer, olive strokes—that keep the surface breathing. The fabric’s mass is credible, yet he avoids clotted paint or minute creases. This architectural handling of cloth is central to the canvas’s dignity: the sitter becomes a column of color that holds its own against the encroaching black.

The Pink Chair as Counterform

The chair is essential to the portrait’s mood. Its rounded top frames Laurette’s head in a halo of warm pattern, softening the austerity of the black field. Along the left and right edges, the chair’s arms flare outward, repeating the robe’s diagonal and catching the light with pale lilac and powder pink. The floral pattern is suggested with mottled dabs rather than rendered leaf by leaf; it is color, not botany. This soft, almost maternal chair wraps the sitter without swallowing her, emphasizing how the robe’s green stands independent within a cushion of pink.

Light, Value, and the Redistribution of Illumination

Instead of a single light source, Matisse distributes value to serve the design. The black field sits at one end of the scale; the robe occupies a middle register with darker accents; the highlights collect along cheekbone, throat, and the top planes of the chair. The hands and shoes offer small, controlled bursts of light low in the composition. This redistribution clarifies the silhouette and makes the face legible without resorting to theatrical chiaroscuro. In a room with no windows shown, light seems to emanate from the color itself.

Surface, Brushwork, and Evidence of Revision

The painting’s surface is tactile. In the robe, long strokes follow gravity’s fall, occasionally turning crosswise to suggest a fold. In the chair, the brush dabs and lifts, producing the softly pebbled feel of patterned upholstery. The black ground reveals both thin scumbles and more saturated patches, signs that Matisse reconsidered the extent of the field as he worked. There are tiny haloes at the robe’s edge where an earlier contour peeks through, proof that the final clarity was achieved through editing. This living surface keeps the portrait human, not machined.

Negative Space and the Crafting of Silence

What is not painted matters as much as what is. The black expanse is deliberate silence, an acoustical chamber for color. Because the surrounding world is withheld, every object assumes symbolic weight. A small loop of ocher near the lower right hints at a chair leg or the glint of a footrest, but Matisse refuses to explain. That refusal grants the sitter absolute priority and allows the viewer’s mind to breathe. The negative space is not emptiness but a chosen quiet in which the portrait can speak.

Relationships within the Laurette Series

Compared with frontal, bust-length images such as “Laurette with Long Locks,” this reclining portrait highlights the model’s languor and elegance. Both pictures share the masklike face and defined contour, yet “Lorette in a Green Robe against a Black Background” leans more heavily on color-blocked architecture. The robe’s monumental plane and the chair’s pink counterform test how figure and ground can be fused without losing the sensation of a person in a room. Together, the Laurette canvases map Matisse’s range: decorative abundance balanced by modern order.

Cultural Echoes and the Modern Interior

The scene includes faint traces of Matisse’s fascination with North African textiles and ceremonial deportment, but they arrive filtered through the Paris studio. The robe’s expanse evokes a kaftan’s dignity; the chair’s floral field hints at an Orientalist textile. Yet everything is distilled to contemporary abstraction. The modern interior is not shown through architectural details but through the boldness of planes and the confidence to let color serve as structure. It is a room built from hue.

Symbolic Resonances without Allegory

Viewers often read the color triad symbolically: green as renewal or poise, pink as intimacy, black as silence or depth. Matisse leaves the door open to such associations while refusing allegory. Nothing in the painting pushes the viewer toward a single narrative. Instead, relationships—robe to chair, figure to field, warm to cool—do the expressive work. The portrait’s serenity is not passive; it is achieved by balancing these relations so that no element dominates.

How to Look

The painting rewards a rhythm of far and near. Take in the whole from a distance to feel how the green robe sets the key and how the pink chair holds it. Notice how the black ground remains active yet recessive. Then approach to see the brush’s turn at the robe’s sleeve, the small flare of highlight across the cheek, and the mottled pinks that keep the chair from freezing. Step back again until the figure resolves into a single, buoyant shape, and you will sense how Matisse composes both a person and an emblem.

Influence and Legacy

“Lorette in a Green Robe against a Black Background” prefigures Matisse’s later method of composing with large, clearly bounded color shapes—the logic that will culminate in his cut-outs. It also speaks to designers and painters today who search for maximum effect with minimal means. The canvas demonstrates that a few planes, controlled intervals of hue, and a decisive contour can build a full psychological presence. This is why the painting still feels startlingly fresh: it is at once intensely personal and rigorously designed.

Conclusion

In this portrait Matisse makes restraint radiant. A single robe of green becomes architecture; a pink chair becomes a gently glowing counterform; a black field becomes an active silence. Within this disciplined framework, Laurette appears calm, self-possessed, and unmistakably present. The painting negotiates between decoration and monument, between surface pleasure and structural clarity, and it does so with the ease of a master working at the height of his powers. More than a century later, the portrait continues to invite long looking and quiet admiration, proof that color and contour—when perfectly tuned—are enough.