Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

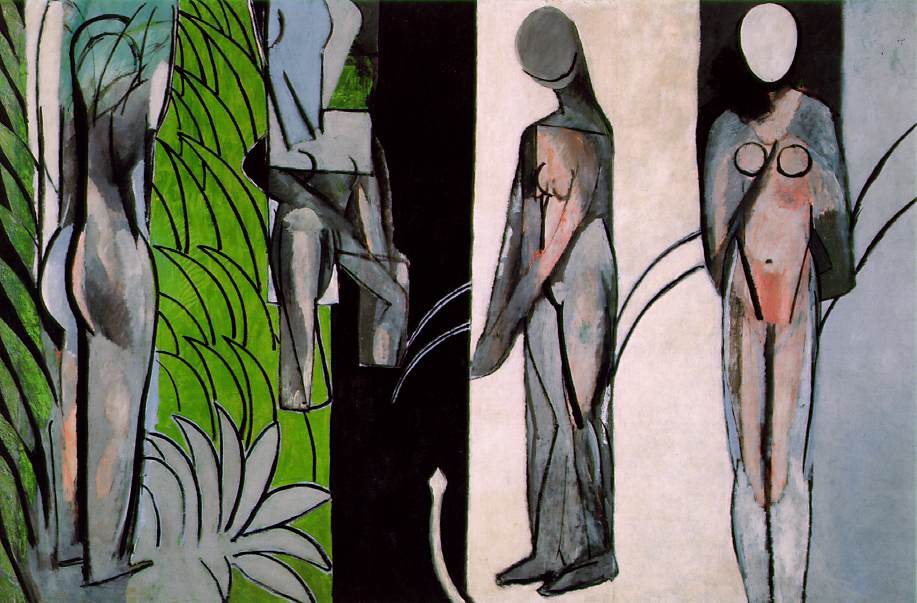

Henri Matisse’s “Bathers by a River” (1916) is one of the most radical transformations of the nude and the landscape in twentieth-century painting. At first glance the image appears almost architectonic: four monumental figures stand like columns, their bodies simplified into slate-gray masses split by razor-sharp contours. Between them, vertical bands of black and white behave like slabs of stone or shafts of blinding light. At the far left, a panel of palm-like foliage in acid green surges upward, its curved fronds echoing and contradicting the rigid bodies beside it. Below, a pale serpent or river curve tips its head toward the center, a single sinuous line that gathers the composition’s tensions. The painting is not a snapshot of bathers in nature; it is a constructed rite, a modern frieze where figure, ground, and symbolism are fused into a rigorous order.

A Work Forged Over Years

Although the canvas is usually dated 1916 to mark its decisive, somber reworking, it was a project Matisse worried over for many years. He began with a decorative conception of brightly colored, idyllic bathers and repeatedly returned to the surface, paring back the sweetness and intensifying structure. The 1916 state—near to the final version—reveals the effect of the war years on his art. The joyous Fauvist palette has been reduced to a handful of grays, blacks, whites, and greens. The sensuous curves of earlier nudes have been straightened, their bodies segmented into slabs like carved stone. The shift from pastoral charm to monumental austerity is not just stylistic; it is a rewriting of what a modern painting of bathers could be.

Scale and Frieze

“Bathers by a River” is large enough to operate as architecture. The figures are more than life-size and carry the authority of a sculpted relief. Matisse distributes them across vertical bands that read like panels, each bather occupying a territory while the whole remains locked together. This frieze-like organization is essential to the painting’s drama. Rather than pulling the viewer into an illusion of depth, the surface holds you at attention. The figures, flattened and frontally aligned, advance toward the plane of the canvas as if to share the room with you. The subject—bathers by a stream—has become a processional presence, both human and totemic.

From Fauvist Color to Charged Restraint

The color speech is deliberately restrained. The green at left feels poisonous and lush at once, a compact symbol of nature. The middle fields are charcoal, blue-gray, and chalky white, with small blushes of flesh color withheld for the breasts, pubis, and a few angled shadows. Black slices create sudden voids, particularly between the second and third figures, driving a wedge into the group. The palette’s economy heightens impact: each color functions as a structural piece, not a descriptive flourish. The greens tangle with the leftmost bather, the black presses cold between bodies, the white band becomes a merciless glare of daylight, and the grays turn skin into stone.

Drawing as Architecture

The drawing is austere and decisive. Matisse lays hard edges down the length of limbs, shoulders, and hips, then softens them with chalky modeling that gives each figure bulk without illusionism. The faces are reduced to ovals and masks; in two cases they are blank white discs, an erasure that turns person into emblem. Across the surface, short diagonal hatchings flicker like cuts in stone. Contour here is not a mere outline; it is an armature that locks bodies into the grid of bands. The eye notices how each figure is “broken” by a slash—across the shoulders of one, at the waist of another—as if to suggest a multiple-view sculptural logic. The body is reimagined as a stack of volumes, not a supple envelope.

The Four Bathers: Variations on a Theme

Each figure is distinct, and their differences give the painting its rhythm. On the far left stands the back view, buttocks and calves set against the green leaves. The second figure is partially occluded, bent slightly, its torso intersected by the strip of black that folds the space. The third is a tall pillar with drooping head, turned inward, its modesty or melancholy conveyed by the sweep of an arm. The fourth, on the right, is the most frontal, breasts circled and head a blank white mask. She is both statue and sentinel, a culminating note of stillness after the interior turn of the third. The sequence moves from living foliage toward pared abstraction, a journey from nature’s curve to the column of human form.

The River and the Serpent

At the bottom center a pale, crooked line lifts and turns like a water snake or a glint of river. This small motif is the hinge of the entire composition. It bends against the verticals, introduces motion into the frieze, and literalizes the painting’s title. It may be read as river water splashing, as a serpent from myth, or as a simple arabesque to adjust the visual pressure of the bands. Matisse leaves it ambiguous, allowing a single curve to hold together nature, fertility, and danger. The austerity above is suddenly touched by a living gesture.

Nature as Panel

The leftmost band is a painting within the painting. Its stylized palm leaves are drawn with heavy, rhythmic curves, each frond reaching upward like a wave. This panel is the memory of Fauvist joy compressed into a vertical strip. It refuses realism—no branch emerges, no depth unfolds—yet its density of green reminds you that the setting is not an interior but a riverbank. Against the black and white of the central bands, the green becomes a counterpart, the realm the figures have left or are about to enter.

The Modern Nude Redefined

Matisse’s bathers are neither voluptuous nor anecdotal. The erotic charge is almost entirely sublimated into design. Breasts and pubic triangles are indicated with blunt circles and wedges; no faces perform; no foamy stream laps at feet. The body becomes a module and a measure. This redefinition of the nude is crucial. The painting insists that a modern image can honor the human figure without capitulating to naturalistic charm. It restores gravity to a genre that had risked becoming decorative pastoral.

Rhythm and Repetition

Repetition governs the painting but never freezes it. Four vertical figure-bands are countered by four or five lateral cues: the river curve, the split across the torsos, the echoed stance of closed legs. The similarity of poses encourages a scan from left to right, while small deviations keep that journey active. The left figure turns away; the next is segmented; the third presents a diagonal of arm and tilted head; the fourth stands frontally like a door. Rhythm arises from these variations—almost musical in their sequence of rest and stress.

Light as Structure

The white band that occupies the fourth panel is not merely a background; it is light incarnate. Where it meets a figure, edges sharpen and forms turn statuesque. In the central blacks, by contrast, contours soften and bodies feel submerged. Matisse uses zones of value—a whole column of white or black—to declare conditions of light rather than model it across each body. The result is clarity at the macro scale. You do not have to chase small highlights; the painting tells you in broad architecture how the world is lit.

Surface and Evidence of Revisions

The surface is layered with decisions. Under the ash-gray of the third figure you can sense earlier colors buried like fossils. Along the edges of the foliage and on the rightmost thigh small haloes of another paint state persist. These pentimenti reveal how the final austerity was reached by subtracting rather than adding. Matisse edited the pastoral to find the monumental. The rubbed passages and scraped backs give the bodies the chalk-stone feel that carries so much of the work’s gravitas.

Dialogues with Cubism and Primitivism

The painting remains entirely Matisse, yet it absorbs lessons from Cubism’s structural toughness and from the so-called “primitive” sculpture that galvanized early modernists. The segmented torsos, the mask-like heads, and the insistence on frontality value construction over illusion. But Matisse refuses Cubist facetting. He keeps the integrity of the figure as a single emphatic column and instead fractures it with a few decisive cuts. Where others multiplied viewpoints, he reduces them, finding drama in restraint.

The War and the Mood

The wartime context matters. Color is quieted; play gives way to severity; the human body reads as enduring matter. “Bathers by a River” does not narrate conflict, yet its mood is steeled. The painting’s happiness, if one can use the term, is a hard-won harmony—four bodies held upright, a green panel reminding of growth, a slender river curve still moving beneath them. The work offers a kind of ethical order rather than escapist pleasure.

Symbolism Without Program

The painting invites readings that it never locks down. The serpent-river could suggest danger or renewal. The faceless masks allow the bathers to stand for types, not individuals—humanity seen in its elemental state. The foliage hints at a return to origins, a garden that persists despite civilization’s ruptures. Yet Matisse resists turning symbol into allegory. Meaning is carried by relations: verticals meeting curves, stone-like bodies beside living leaves, light bands confronting darkness. The painting’s force lies in that balance rather than in a solved riddle.

How the Composition Works on the Body

To look at this painting is to feel its posture. The verticals ask you to stand up, to align your spine with those columns. Your breathing falls in with the measured spaces between bodies. The left green panel pulls the eye upward; the curved river line drops it to the floor. The painting choreographs viewing as a bodily experience, a simple standing and scanning that echoes the bathers’ own rites at the water’s edge.

Connections to Matisse’s Other Works

“Bathers by a River” sits at a fulcrum in Matisse’s career. Its clarified bodies anticipate the cut-out dancers and swimmers of the 1930s and 1940s, where figure becomes pure contour and color. Its disciplined palette and architectural order tie it to the 1914–1917 interiors with windows and high stools, where single colors are assigned to whole planes. At the same time, the green foliage nods back to the luxuriant ornament of earlier years. The painting gathers past and future strands into a single, stringent statement.

The Poetry of Reduction

What makes the canvas continually compelling is not just its structure but its poetry of reduction. Matisse does not describe hair, toes, ripples, or individual leaves. He selects the fewest signs that will conjure a world: a leaf crescent, a breast circle, a black abyss, a chalky thigh. Because each sign is necessary, none is decorative. This leanness allows the painting to expand in the mind; viewers bring their own water, weather, and human story to fill the spaces the artist has carved.

Lessons for Looking

The most rewarding way to encounter the painting is to alternate distance and proximity. From several steps back, absorb the four-beat rhythm of its columns and the way the green left panel speaks to the white right panel across the span of grays. Then approach to see the dry scumbles and dragged lines that give the bodies a sculpted surface. Notice the small coral flush at the pubis, the charcoal hatch that defines a calf, the brush’s turn where a leaf tucks behind a thigh. Return to distance so the scene resolves again into order. That oscillation—between architecture and touch—is where the work reveals its full life.

Why It Endures

“Bathers by a River” endures because it does something paradoxical and rare. It reduces the human figure almost to a symbol while preserving a grave tenderness. It collapses the idea of nature into a handful of shapes without losing the sense of an outdoors. It refuses spectacle and yet feels monumental. In it, Matisse finds a language equal to a difficult moment—severe but not bleak, calm but not complacent. The bathers, poised and mute, seem to wait for a signal to step into the water. That poised waiting is the painting’s heartbeat.