Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

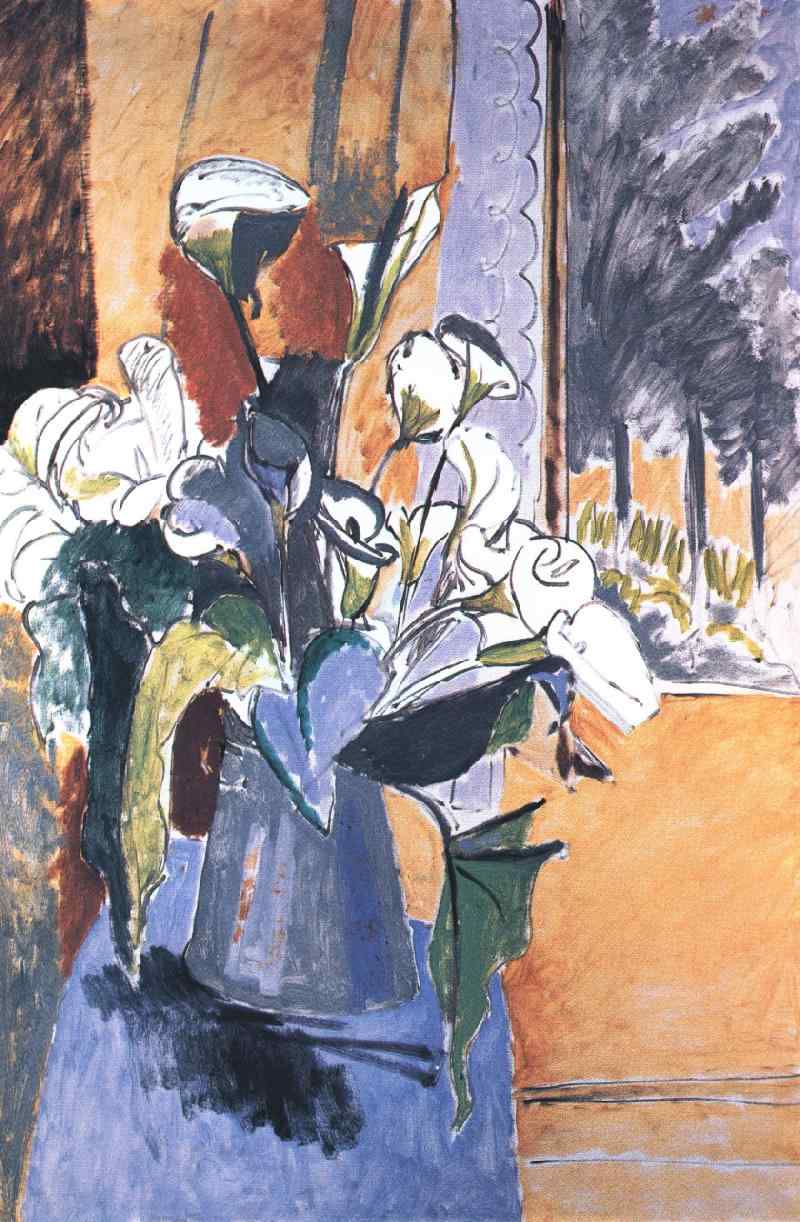

Henri Matisse’s “Flowers on the Windowsill” from 1913 distills an ordinary domestic sight—a vase of calla lilies set near a window—into a charged experiment in color, contour, and spatial compression. The painting’s force lies not in naturalistic description but in the way each element is transformed into a rhythmic sign. With sweeping outlines, abrupt blocks of ochre and blue, and a window that doubles as a flat panel and a view outdoors, Matisse converts the interior into a stage where color performs the work of structure. The result is a still life that seems to breathe, tilting between intimacy and monumentality, between a private corner of a room and a bold proposition about what painting can be.

Historical Moment

In 1913 Matisse stood at a pivotal juncture. The explosive color of his Fauvist years had matured into a more deliberate architecture of planes, and his attention had turned increasingly toward interiors framed by textiles, screens, and windows. Rather than follow Cubism’s fragmentation of objects into faceted geometries, he pursued an alternative route to modernity: the assertion of decorative surface, the clarity of contour, and the conviction that color itself can construct space. “Flowers on the Windowsill” belongs squarely to this inquiry. It is neither a retreat to tradition nor a mimicry of avant-garde fracture; it is Matisse’s synthesis—flat, frank, and saturated with feeling.

First Impressions

The first encounter with the canvas is striking for its bold, high-contrast palette. A dense bouquet of white calla lilies and deep, bluish leaves rises from a solid bluish-gray jug, resting on a slate-blue tabletop. Behind the bouquet, a broad field of ochre glows like sunlit plaster, interrupted by assertive verticals that read as shadowed muntins or a screen. To the right, the window opens onto a simplified landscape of violet-gray trees and orange ground, framed by a lilac strip scalloped like an embroidered border. The whole scene feels both sketched and decisive, as if Matisse captured a single breath of light and then fixed it in declarative shapes.

The Motif of the Window

A window is more than just a prop; it is a conceptual engine. In this painting the window provides a hinge between interior and exterior, flatness and depth, earthbound object and atmospheric view. Matisse positions the bouquet where domestic decoration meets the world outside. The lilac, scalloped inner border operates like a decorative frame within the picture, acknowledging the window’s status as an image inside an image. The view of trees and orange ground is simplified to the point of emblem: vertical trunks, cloudlike foliage, and a band of earth. By flattening the view even as he offers it, Matisse asserts that the landscape beyond and the arrangement within share the same pictorial logic.

Composition and Balance

The composition pivots around a strong diagonal sweep from lower left to upper right, generated by the table edge and the rising stems. The triangular mass of the bouquet locks to the rectangle of the window, producing a cross-shaped tension that stabilizes the picture. The jug stands slightly left of center, creating asymmetry that Matisse counterweights with the bright ochre panel and the exterior view to the right. Large, leaf-shaped forms hang down and thrust upward, alternating convex bulges with spear-like points. The result is a dynamic equilibrium: the flowers feel animated, yet the overall structure reads as calm and deliberate.

Color Architecture

Matisse builds the painting with a small but potent set of hues—blues and lilacs against ochres and oranges, accented by greens and the pure whites of the lilies. The complementary pairing of blue and orange drives the canvas. Blue anchors the jug and tabletop, cools the leaf shadows, and carries through the window’s border; orange enlivens the wall and the outdoor ground, radiating warmth that seems to backlight the bouquet. White is not a neutral void but an active color, set off by black contour so that each calla becomes a crisp, luminous statement. Green appears in measured doses to bridge the cools and warms, keeping the palette from splitting into opposing camps. The harmony is orchestral: a few instruments, masterfully tuned.

Light and Atmosphere

Despite the emphasis on flat color, the picture thrums with light. The ochre field behaves like a sun-warmed wall, and the white lilies register as forms that catch and flare, not through modeled shading but through contrast with adjacent tones. The outdoor zone is bathed in a different light—cooler, more diffuse—and that contrast underscores the boundary between room and view. A dark patch on the table functions like a cast shadow, but it also reads as a deliberate brushy counterform that secures the vase to its ground. Matisse thus conveys illumination without theatrical modeling, proving that light can be inferred by color relationships and edges alone.

Drawing, Contour, and the Expressive Line

The painting’s drawing is assertive, almost calligraphic. Thick black lines outline petals, leaves, and the profile of the jug, while thinner, searching lines describe stems and delicate edges. These contours do not only delineate forms; they energize them. A single curved stroke can suggest the roll of a calla’s spathe; a jagged mark can convert a leaf from botanical detail into a decisive wedge. In places the line seems to slip from describing the object to inventing it, evidence of Matisse’s belief that drawing is not a transcription but a creative act. The interplay of heavy and light contour also regulates the rhythm of looking—some passages feel weighty and anchored, others quick and aerial.

Brushwork and Surface

The surface varies from scumbled, almost dry passages to dense, opaque swathes. The blue tabletop shows transparent scrubs that let a lower tone breathe through, as if the painter adjusted the value on the fly. The ochre field carries vertically dragged strokes that echo the window’s uprights. On the leaves, one can sense wet-in-wet charges that achieve rich greens by mixing on the canvas rather than on the palette. This variety keeps the surface alive and resists monotony, yet the handling is never fussy. Even the rough edges at the canvas margins feel purposeful, a reminder that the picture is a made object and not a window pretending to be invisible.

Pattern and the Decorative Impulse

A narrow lilac band with scalloped ornaments runs beside the window, an exquisite acknowledgment of textile and craft tradition. That modest strip crystallizes the painting’s decorative ideal: repetition, simplification, and pleasure in surface. It also forges kinship between the natural forms of flowers and the invented forms of pattern. The scallops repeat the arcs of the calla petals and the jug’s belly, tying disparate elements into a single visual grammar. Matisse makes it evident that decoration is not embellishment after the fact; it is a structural principle that orders the whole.

Flatness, Depth, and Productive Ambiguity

The painting stages a sustained game between shallow relief and deeper space. The tabletop reads as a single plane tilted up, yet the vase sits solidly upon it. The window is both a flat panel and a recess; the outside trees float as silhouettes but also drift backward into atmospheric haze. Rather than resolve these contradictions, Matisse preserves them as the engine of the painting’s vitality. The viewer’s perception toggles: at one moment the bouquet presses forward like cut paper; at the next it swells into a palpable mass. This oscillation is not a failure of illusion but the modern condition Matisse chooses to celebrate.

The Bouquet as Character

The calla lilies are the painting’s protagonists. Their white trumpets curl and pivot with a sculptural firmness that thrives under Matisse’s simplification. The leaves are not botanical portraits; they are emblematic shapes—heartlike, spear-like, crescent—each with its own temperament. Some leaves are filled with solid, cool color; others are streaked with earthy tones that echo the ochre wall. The bouquet is simultaneously cultivated and untamed, arranged but restless. It embodies a paradox dear to Matisse: art as disciplined spontaneity, an ordering of forces that preserves the sap of life.

The Outdoor View

Through the window the world is reduced to broad, legible bands: a swath of orange ground, verticals for trunks, cloudlike foliage rendered in lavender and gray. The simplification is so extreme that the view approaches abstraction, yet it retains enough cues to read as landscape. That outdoor strip also functions as a color relay. The orange there answers the indoor ochre, while the grays and violets harmonize with the lilac border and the blue tabletop. Matisse refuses to let outside and inside be separate realms; they converse across the frame, passing chords back and forth.

Gesture, Revision, and the Trace of Process

A sense of process remains visible. Pentimenti in the leaves and stems suggest that forms were moved or reshaped during painting. Broad slashes of dark paint behind the bouquet may mark earlier placements of a curtain or shadow. Such traces are not cleaned away; they animate the surface and invite the viewer into the studio. The painting feels provisional in the best sense—not unfinished but open, candid about the path by which conviction is reached.

Dialogue with Contemporary Movements

The picture enters into dialogue with the dominant currents of its time. Where Cubism fractured the window into prismatic planes, Matisse keeps the window intact while flattening it into a decorative panel. Where Expressionism pushed distortion to convey psychic urgency, Matisse chooses restraint, letting color and contour carry emotion without contortion. He proves there was another way forward for modern painting: clarity without coldness, joyous color married to architectural order, intimacy scaled to the condition of the decorative.

Interior Life and Modern Domesticity

The painting offers a portrait of modern domestic life without figures. The jug, the table, the patterned border, and the view together suggest a room curated for pleasure and clarity. It is a setting where art and everyday living are inseparable; flowers are not only natural specimens but instruments for orchestrating the interior. The window’s openness suggests permeability between home and world, a permeability that art heightens rather than denies. In this sense the work is not just a floral still life but a manifesto about dwelling with color.

Time, Season, and Sensation

Hints of season permeate the canvas. The orange ground outside and the darkened tree masses imply late afternoon or a sun-soaked, warm climate. Inside, the cool blues of the tabletop and jug temper the heat, producing a perceptual breeze. The lilies, associated with ceremony and elegance, contribute a sense of occasion, as if the moment of painting were chosen for its particular light. Matisse translates these temporal cues into a timeless order; the mood feels specific yet durable, familiar yet freshly encountered each time the eye returns.

Materiality and Scale

Everything in the image points to Matisse’s sensitivity to material fact—the drag of a loaded brush, the way thin paint sinks into canvas weave, the scuff where one layer meets another. The jug’s body is an accumulation of blue-gray averages rather than a polished glaze, so that it reads as a made thing rather than a photographic object. Scale is established by relation, not measurement: the lilies fill the window bay, the jug weighs properly on the table, the landscape band is slim but legible. Such calibration reveals an artist less interested in illusionistic bravura than in the rightness of relations.

Kinship Within Matisse’s Oeuvre

“Flowers on the Windowsill” aligns with the interiors and floral still lifes Matisse produced around this period, in which curtains, wallpapers, and windows act as equal partners to flowers and vessels. It shares with those works a love of cutout-like shapes, firm dark contours, and color deployed in broad, unmodeled fields. It also anticipates later interiors where odalisques, screens, and patterned cloths create complex, layered stages. Seen in that continuum, this canvas reads like a clear, ringing note—neither preliminary nor redundant, but a necessary articulation of Matisse’s decorative intelligence.

What the Painting Teaches About Seeing

The painting instructs the viewer to read not only objects but relationships. A white petal gains meaning next to an ochre field; a violet border sings because a green leaf crosses it; a dark line is not mere edge but tempo. To attend to these relations is to experience the work as a living system rather than a bouquet placed before a window. Matisse proposes that seeing can be an act of ordering joy, an arrangement of perceptions that clarifies the world without impoverishing it.

Conclusion

“Flowers on the Windowsill” turns a modest subject into a lucid demonstration of pictorial thought. The bouquet, the jug, the window, and the view beyond are handled as equal players in a drama of color and line. Flatness and depth negotiate rather than battle; pattern binds rather than decorates; light emerges from adjacency instead of shading. In its poised vigor the painting embodies Matisse’s belief that art can be both restful and alive, both simple in means and inexhaustible in experience. To spend time with it is to feel the room brighten, as if a window has been opened not only in the wall but within the act of looking itself.