Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

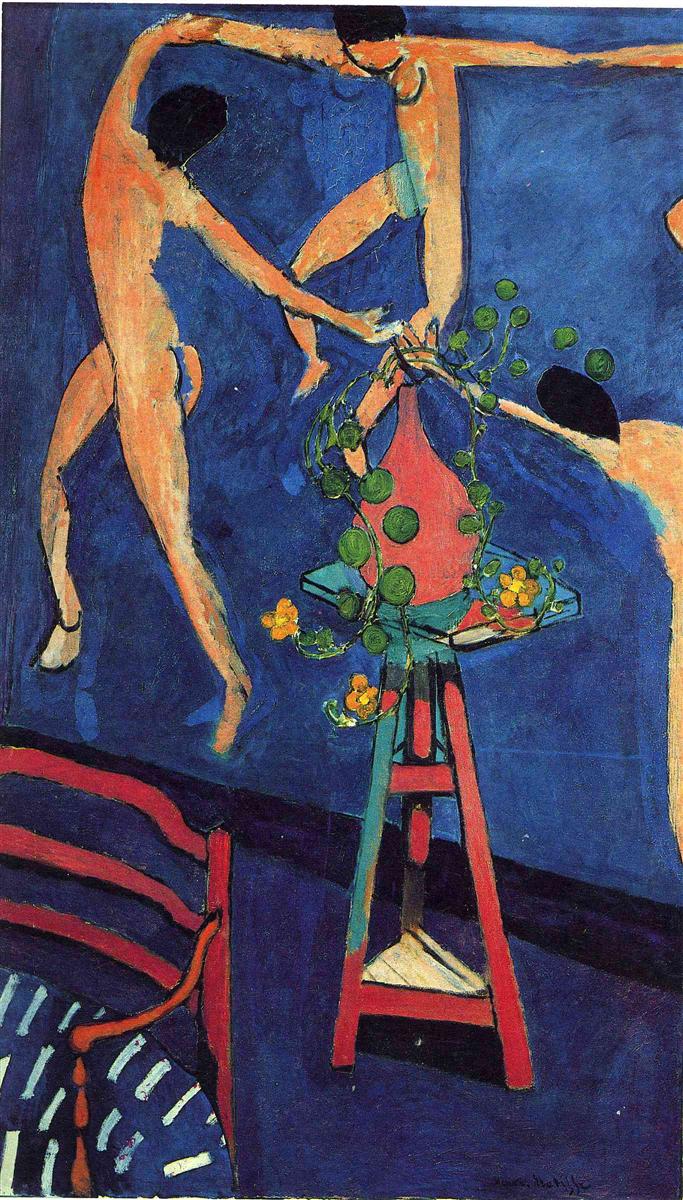

Henri Matisse’s “Nasturtiums with ‘The Dance’ (II)” (1912) is a studio picture that stages an exhilarating encounter between the intimate still life and the monumental decorative mural. A tall red vase crowned with a green trailing vine and flares of yellow nasturtiums sits on a small table propped on a bright trestle. Behind it, cropped by the edges of the canvas, the linked nudes of Matisse’s earlier composition “The Dance” sweep across a field of saturated blue. A striped chair and a fragment of rug occupy the lower left, anchoring the foreground like low musical chords. The composition is at once familiar and newly daring: the studio appears again as a theater in which color, contour, and rhythm perform, yet this version turns the dial toward verticality, compression, and speed. Everything presses forward to the surface, and everything moves.

Historical Moment

The year 1912 stands at the crossroads of Matisse’s mature language. He had already transformed Fauvism’s experiments with high-key color into a broader program of clarity and equilibrium, and he was fresh from the shock of Moroccan light—a shock that reinforced his attraction to large, flat fields of blue and his desire to paint the experience of illumination rather than its optical description. At the same time, Paris was witnessing the ascent of Cubism’s analytic grammar. Matisse chose a parallel modernism: he would not fracture objects into facets but would fuse them into rhythmic wholes by means of color intervals and sweeping arabesques. “Nasturtiums with ‘The Dance’ (II)” crystallizes that choice and makes it personal by quoting his own monumental dancers, originally painted for the Russian collector Sergei Shchukin, inside the private space of the studio.

Vertical Format and Cropping

Unlike the horizontally oriented version of the subject, this second painting is a tall, narrow rectangle. The change in format changes everything. The ring of dancers cannot complete itself; it bursts against the edges, sending limbs diagonally through the field like lightning. The red trestle, the vase, and the vine rise along the same axis, a vertical counterpoint to the dancers’ centrifugal sweep. Cropping becomes a structural device. By allowing figures and furniture to shear off at the edges, Matisse intensifies the sensation of proximity, as though the viewer has stepped in too close—an intimacy that suits the studio setting and underlines the painting’s modernity.

Composition and Geometry

The painting’s geometry is a choreography of lines and shapes that bind movement to stillness. A strong diagonal leads from the left dancer’s arced arm to the intertwined hands at center, then down the vine’s curve to the crosspiece of the little table and the splayed legs of the trestle. The vase itself is a bulbous red tear, echoed by circular green leaves that bead along the vine like notes on a staff. The chair introduces three shallow crimson arcs that rhyme with the dancers’ backs and the tabletop’s outline. These echoes distribute energy across the surface so that no zone remains inert. The composition is a web in which each curve calls and another answers.

Color Architecture

Matisse builds the scene out of a compact architecture of color. The ground is a deep, maritime blue spread in wide, opaque slabs, varied by scumbles and patches that let warmer underlayers breathe through. Against this all-encompassing coolness he sets the warm family of reds and oranges: the trestle’s vermilion legs, the crimson vase, the coral undertones of the dancers’ skin, the hot chevrons of the chair. Green enters as mediator—present in the vine and leaves, cool enough to sit with the blue yet warm enough to harmonize with the red. Yellow is reserved for decisive accents in the blossoms and the tabletop edges, small sparks that keep the eye in play. The complementary pairing of blue and orange-red drives the painting’s electrical charge; the greens and yellows tune that charge into harmony rather than clash.

The Vase, Vine, and Nasturtiums

Matisse’s choice of nasturtiums is both practical and poetic. Their round, coin-like leaves and bright flowers reduce beautifully into flat signs without losing botanical identity. In this canvas the leaves become a string of circular beats that coil around the vase and spill onto the tabletop, a rhythmic foil to the dancers’ oval heads and hips. The vine also serves as a line that physically ties the still life to the human ring behind it: its tendrils loop in sympathy with linked hands, as if life in the pot were learning the choreography in miniature. The red vase is not modeled in the traditional sense; its volume is declared by contour and by its contrast with the ground. Yet it feels weighty, a compact heart at the painting’s center whose pulse spreads through the greenery and into the dancers’ rhythm.

“The Dance” as Backdrop and Engine

By quoting his own painting, Matisse collapses public and private work, monumental and intimate scale. In “Nasturtiums with ‘The Dance’ (II)” the dancers do not sit passively as decoration; they generate the room’s energy. Their limbs enter from the edges, their torsos twist, their clasped hands ignite a kinetic chain reaction. The wall that bears them seems not a stable partition but a vibrating field. The dancers are both a picture on the wall and a force in the room, a paradox Matisse relishes. The still life becomes the choreography’s partner: on the floor and the tabletop are props, but on the wall is the reason everything vibrates.

Movement and Stillness

The painting’s central drama lies in the friction between kinetic figures and stationary objects. The trestle, angular and architectural, grips the ground; the vase sits firm; the tabletop is a small stage. Yet the dancers tug the whole ensemble into motion. The vine registers that pull, curling toward their hands; the yellow blossoms scatter like notes struck from a string. This friction is not conflict but counterpoint. The stillness allows us to feel the speed; the speed keeps the still life from becoming inert. Matisse shows that stability and motion are not opposites but partners in a balanced composition.

Space Without Conventional Perspective

As in much of Matisse’s work from this period, depth is created not by vanishing points but by the stacking of zones and the pressure of color. The wall is a flat blue field that reads both as near and far. The trestle and chair rest on a darker band of floor, but no orthogonals thrust into imaginary distance. Overlap does the work of depth: the trestle stands in front of the wall, the chair rises in the lower left corner, and the dancers cross the field behind the tabletop. This simplified spatial system keeps attention on rhythm and harmony rather than on illusion. The viewer is invited to feel space as a set of relationships rather than to walk into it.

The Studio as Theater

Matisse consistently used his studio as a stage where paintings, objects, and human bodies could play roles. Here the trestle functions like a prop pedestal; the chair provides a foreground note that tells us where we, as viewers, are seated; the rug fragment is a cue mark on the floor. The painted mural becomes the theatrical backdrop. The studio is not simply depicted; it is performed. By situating a famous image from his own oeuvre within that stage, Matisse also performs authorship. He demonstrates that his art is not a sequence of isolated statements but a repertoire that can be recombined into new harmonies.

Dialogue with the First Version

Comparing this second version to the earlier “Nasturtiums with ‘The Dance’” reveals the nature of Matisse’s experimentation. In the first canvas the composition breathes horizontally, with the tabletop spreading like a calm island and the dancers circling above. In the second, tension increases. The vertical format compresses the action; the trestle elongates; the vine becomes a taut rope connecting wall and table; the dancers are cut more aggressively by the edges. The shift is not about improvement but about testing how the same motifs behave under different conditions. The second version is the swift, high-register variation—a scherzo to the first version’s andante.

Material Surface and Brushwork

The surface of the painting reveals the discipline behind its apparent spontaneity. In the blue field the brush moves in broad, almost masonry-like swaths, building the wall as if laying stones of color. Along the edges of limbs and objects, Matisse often leaves a halo of lighter paint or a seam where two colors meet, turning the act of painting into visible drawing. The trestle’s reds are layered and sometimes coolly edged with a turquoise stroke that makes them vibrate; the vine’s leaves are quick disks with a darker ring and a lighter center, enough information to make them pop. Everywhere the touch remains economical, giving just what is needed for the form to live and nothing more.

Line and Arabesque

If color provides the music’s harmony, line supplies the melody. One can hum the painting’s contours: the arc of clasped arms, the rounded flare of the vase, the serpentine vine, the chair’s scalloped rails. Matisse’s line is firm yet elastic, never stiff. It behaves like a dancer’s body: stretched, curved, sprung back. In several places the line is implicit rather than drawn—the edge where red meets blue or green meets blue becomes a living contour. This fusion of drawing and color keeps the image unified and ensures that no passage of line feels merely cosmetic.

Rhythm of Circles and Diagonals

A recurring theme in the painting is the circle interrupted by diagonal thrusts. The dancers aim to form a ring but are sliced by the frame; the vine beads into circles that scatter across a diagonal stem; the chair’s arcs are cut by vertical posts; even the tabletop—nearly a diamond—suggests rotating movement pinned by a crosswise trestle. This geometry produces a dynamic of turn and counterturn, as if the composition itself were spinning slowly while the trestle keeps time like a metronome.

Reading the Chair and Rug

The lower left corner, with its reddish chair and fragment of a patterned rug, might seem incidental, but it performs crucial work. The repetition of red in the chair stabilizes the trestle’s warmth and extends the color’s reach to the bottom fringe of the picture. The stripes of the chair rails mirror the dancers’ linked arms in miniature, establishing a lower echo of the upper rhythm. The rug’s white strokes against blue, curved like calligraphic marks, contribute a whisper of pattern that keeps the floor from reading as empty void. These domestic notes ground the performance in the lived reality of the studio.

Light and Atmosphere

There is no naturalistic source of light, yet the painting glows. The blues are tuned so that certain zones read as cooler depths while others lift toward the surface; the reds lean warm but are cooled by bordering strokes; yellow blossoms flare like tiny lanterns. The overall effect is of indoor light suffused through colored matter rather than cast from a directional lamp. Matisse produces atmosphere by calibrating saturation and value, proving that a few tones, properly balanced, can make air.

Psychological Tone

Despite the athletic vigor of the dancers, the picture radiates poise rather than frenzy. The trestle’s structural certainty, the vase’s calm mass, and the measured cadence of leaves temper the action. The result is a festive serenity—a state Matisse often pursued—where intense sensation is held within a restful order. It is an image of happiness that has learned discipline, a celebration that knows how to sustain itself without excess.

Symbolic Readings

The painting invites symbolic associations without leaning on them. The nasturtiums suggest cultivated nature, tamed and arranged; the dancers suggest communal joy and unselfconscious physical grace; the vine that ties them together hints at the organic connection between art and life. The trestle, an artist’s piece of studio furniture, stands for making—the craft that supports vision. Yet the true symbols here are pictorial: blue against red, circle against diagonal, wall image against tabletop presence. Meaning emerges through the pleasure and clarity of these relationships.

Relation to Modern Painting

In 1912 painters were asking how a canvas could be modern without obeying the rules of Renaissance space or descriptive modeling. Matisse’s answer in this work is that a painting can be built as a decorative whole whose parts are tuned like instruments in an ensemble. He refuses illusionistic depth in favor of layered planes; he refuses heavy shadow in favor of color value; he refuses exhaustive description in favor of telling signs. The result is not mere stylization but a new naturalism of sensation, capturing how the eye actually organizes experience when it is alive to rhythm and color rather than to neutral record.

Why This Work Matters

“Nasturtiums with ‘The Dance’ (II)” matters because it demonstrates, in condensed form, how Matisse could unify wildly different orders of experience—an epic mural, a modest vase of flowers, and the place where both exist—into a single, convincing world. It proves that a painting can be both reflective and immediate: reflective in the way it revisits an earlier masterpiece, immediate in the way it makes objects pulse with present tense. It also shows a painter thinking compositionally across his own oeuvre, treating past motifs as living tools rather than as trophies. Above all, the work argues for painting as a generator of happiness, not by sentimental subject matter but by the precise tuning of form and color.

Conclusion

Tall, compressed, and exhilarating, “Nasturtiums with ‘The Dance’ (II)” transforms the studio into a charged arena where movement meets repose. Dancers spin across a cobalt wall; a red vase vines upward on its trestle; a chair and rug whisper of everyday life. Between these elements Matisse composes a music of circles and diagonals, blues and reds, cool atmospheres and warm accents. The painting feels inevitable, as if the world had always wanted to be organized this way but needed Matisse to hear its rhythm. It is both a love letter to his own “Dance” and a manifesto that art, like a good bouquet, can gather diverse energies into a single living form.