Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

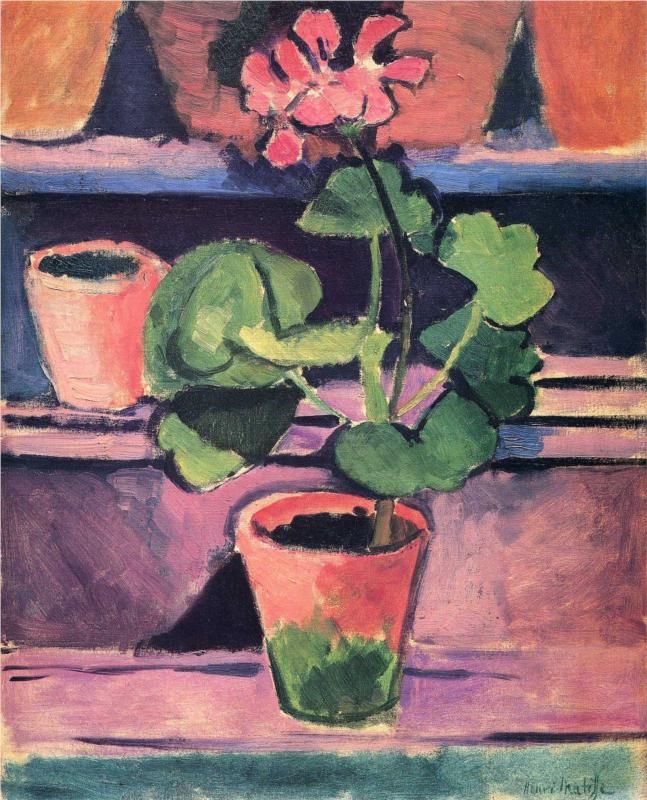

Henri Matisse’s “Pot of Geraniums” (1912) is a small painting with large ambitions. A single potted plant rises from a tabletop or shelf, its round leaves and a pink bloom silhouetted against a field of mauves, violets, and midnight blues. Nearby, a second pot sits half in shadow, its opening a dark oval that deepens the space without resorting to conventional perspective. Thick, confident brushstrokes articulate the structure of the plant; blackish contours snap edges into focus; and broad passages of color—coral reds, blue-violets, inky greens—build the picture like a mosaic. The subject is modest, but the treatment is uncompromisingly modern. Matisse turns an ordinary geranium into a lesson on how color can be architecture, how drawing can be painted rather than penciled, and how still life can aspire to the condition of music.

A Domestic Subject with Monumental Presence

Geraniums are familiar housemates: sturdy, bright, and tolerant of sun. Matisse selects this humble plant not as a symbol but as a structure. The plant supplies a simple yet expressive grammar of forms—circular leaves, vertical stems, a soft burst of petals—that can be arranged like notes on a staff. Centering the geranium in its own terracotta pot gives it the gravity of a portrait subject. The pot’s tapered cone, rimmed in a darker red and stained with green at the base, sits squarely on a lavender plane that reads simultaneously as table and stage. Behind it, the shelving or window ledges step back in horizontal bands, creating a shallow amphitheater around the star. Nothing distracts from the plant’s presence; all other objects are supporting actors that explain the space and amplify the central rhythm.

Color as Architecture

“The Pot of Geraniums” is built almost entirely from color. Matisse’s palette gathers three families and tunes them into harmony. First is the warm coral-red of the pot and the bloom. It is not a screaming scarlet; it is moderated by earthy orange and rose, allowing the color to feel close to terracotta and flesh at once. Second is the cool spectrum of violets and blues that lay out the background planes. These hues move from smoky plum to near-indigo, with dry-brush scumbles that let the prepared canvas flicker through. Third is the green family: not one green but many—sap, bottle, viridian, olive—deployed in leaves that carry gentle notes of yellow and blue. Red and green, classical complements, take the main duet; violet and green supply a secondary, subtler counterpoint. The result is an architecture of chroma: walls, platforms, and voids constructed not with lines, but with fields of tuned pigment.

Drawing with the Brush

Matisse’s draughtsmanship shows in the way he lays a stem or edges a leaf with a single, loaded stroke. Contour is never fussy. A curved line runs along a leaf’s rim and thickens or thins with wrist pressure, setting both edge and shadow at once. Where two leaves overlap, he sometimes places a narrow strip of dark between them, not to imitate cast shadow, but to keep the forms legible. The pot’s rim is a brisk ellipse, not a labored construction; its interior is not modeled but declared with a flat dark that reads as depth only because surrounding colors are lighter. This approach to drawing—painting edges rather than enclosing forms with graphite—lets the surface stay alive and honest. You see what was done, where the brush began and lifted, how decisions were changed by placing one color against another.

The Stage of Horizontal Bands

A set of horizontal slats or shelves divides the picture into tiered bands. Their function is architectural before it is descriptive. The lines stabilize the composition, preventing the plant’s vertical movement from unbalancing the picture. The bands also create beats for the eye: a lavender strip across the bottom, a darker blue mid-band, and a top register that recedes into shadow. These stripes echo the way a musician might break a piece into measures, each holding a separate phrase. Matisse uses their color and value shifts to suggest shallow space—the middle band is darkest, the top a cooler violet—without submitting to strict perspective or cast shadows.

Light by Adjacency, Not by Illusion

There is no single light source in the theatrical sense. Instead, light is built by adjacency. A leaf glows because a darker green lays under its edge; the pot seems sun-warmed because a cooler violet abuts its side; the flower reads as delicate because it interrupts the dense violet field with coral pinks edged by charcoal. Highlights are seldom dabbed on as white; they are created when a pale violet meets a deeper purple or when a warm red edge is trimmed by a cooler brush return. This method produces a light that belongs to the surface of the picture rather than to an imagined world beyond it. Illumination becomes a property of color relations.

The Geranium as a Modern Motif

Matisse had painted geraniums before, but by 1912 his approach matured into this poised economy. The plant’s character—upright stems, round leaves—suited his desire for forms that could be simplified without losing identity. The geranium also provided a practical vehicle for exploring complementary color. Red petals tempt clichés; Matisse resists by keying them into coral and salmon, then setting them against a sophisticated violet environment that lets the reds vibrate rather than shout. The plant becomes a modernist motif: recognizable, expressive, abstractable.

Material Surface and the Pleasure of Paint

One of the painting’s quiet pleasures is its surface. In the background, thin layers are dragged across rough canvas, catching on the weave and leaving a shimmer of undercolor. On the pot and leaves, paint is thicker, sometimes pushed with a short brush to build a soft ridge along an edge. You can track Matisse’s order of decision: the wide violet field laid first, the bands pulled across it, the pot dropped in like a brick of color, and the plant grown with strokes that chase each other across the surface. Occasional pentimenti—a leaf shifted, a stem trimmed—remain visible, proof that the painting was argued into being rather than pre-planned.

Structure and Balance

Despite its immediacy, the composition is very carefully balanced. The high bloom leans left, but the weight of the pot and a mass of darker leaves to the right counter it. The second pot at left—a pale vessel with a blackened mouth—prevents the central pot from feeling isolated. Negative spaces between leaves are as sculpted as the leaves themselves; they open views to the violet beyond, allowing the eye to rest. The darkest dark—a shadow beneath the pot—locks the plant to its stage, while the lightest light—the pale lilac plane—acts as an acoustic panel that amplifies color. Everything holds.

Decorative Rhythm Without Ornament

Matisse is often called “decorative,” sometimes meant pejoratively. Here decoration is not a layer of patterns; it is rhythm. Round leaves repeat with variation, creating beats like drum strokes: big, small, overlapping, clipped. The horizontal bands provide a steady bass line. The bloom adds treble—a syncopated cluster of petals that never freezes into a diagram. This idea of decoration as rhythm lets the painting feel musical rather than ornamental. It invites a temporal reading: your eye moves, pauses, returns, improvises.

Dialogue with Earlier and Later Works

“Pot of Geraniums” converses with a line of Matisse’s still lifes. The coral pot and green leaves recall the earlier “Geranium” of 1909, but the 1912 canvas is more structural, less atmospheric. It also nods to the interiors and studio pictures around 1911—“The Blue Window,” “Red Studio,” “The Pink Studio”—in its reliance on wide color fields and decisive edges. Looking forward, the picture foreshadows the cut-outs: leaf shapes defined by contour and flat color, petals reduced to essential curves, backgrounds as unbroken planes. You can imagine this geranium reappearing twenty-five years later as paper scissored from painted sheets.

Scale and Intimacy

The painting’s relatively small size contributes to its intimacy. You can take it in at arm’s length; the pot seems almost life-size. Yet the handling grants it monumentality. Matisse avoids miniaturist rendering; he paints the geranium with the same breadth he would bring to a large interior. This scaling of gesture—big decisions on a small surface—creates the uncanny feeling that the plant exceeds the frame, that its color-charged presence is larger than its pot.

The Ethics of Simplification

Simplification is risky: take away too much and the subject dissolves; keep too much and the painting clutters. Matisse finds the line. The flower does not show every petal; it registers as a single coral burst with a few separating cuts. Leaves are not veined; their roundness and occasional notch suffice. The pot is not glazed into realism; its tapered cone and dark mouth carry the information. Simplification, here, is an ethical stance: it respects the viewer’s ability to complete the image and protects the painting from the deadening weight of unnecessary detail.

The Psychology of Color

Beyond structure, color also sets mood. The violets and blues create a cool, contemplative atmosphere, like evening in a studio. The coral of the pot and flower warms the scene without breaking its calm; it is the ember in a hearth, not a flare. The greens—earthy rather than neon—anchor the plant in the realm of the natural, keeping the picture from floating off into pure abstraction. Together these colors produce a psychological temperature that matches Matisse’s oft-quoted wish for an art that “provides a soothing, calming influence on the mind.” The painting is not dull; it is peaceful.

Space, Depth, and the Modern Eye

Traditional still-life depth is attained through perspective and cast shadows. Matisse largely discards both. The shelf bands state their positions by overlap and value rather than by converging lines. The pot’s contact with the surface is confirmed by a wedge of dark, nothing more. The second pot in the upper left quadrant helps mark recession because it is smaller and paler, not because it is rendered in aerial perspective. This is the modern eye at work: depth is inferred from relationships, not fabricated through illusionistic tricks.

The Geranium as a Studio Companion

The painting also reads as a studio diary. Potted plants populate many of Matisse’s interiors; they are living models, patient under scrutiny. Unlike cut flowers, a geranium endures. It grows between sittings, shifts a leaf toward light, opens and closes a blossom. In “Pot of Geraniums,” you feel this companionship. The plant is not a luxury item; it is a working partner that teaches the painter about form persistence and color resilience. Its unglamorous steadiness is honored by a composition that is equally steady.

Lessons for Painters and Viewers

From this single canvas, several practical insights emerge. Build an image with families of color rather than with a rainbow; let one family—here, the violets—set the climate. Use complementary contrast to focus attention, but modulate both members so they converse rather than shout. Draw with the brush and trust edges to carry both form and light. Organize space with bands or blocks so the subject has a platform. Simplify relentlessly until each retained element earns its place. These are not only painter’s lessons; they are ways to look: scan for structure, notice intervals, appreciate how small differences in temperature can change a surface’s energy.

Why It Still Feels Fresh

Over a century later, “Pot of Geraniums” looks right at home beside contemporary painting and design. Its limited palette, strong edges, and graphic clarity echo in poster design, brand identity, and even user interface aesthetics. Its modest scale suits contemporary viewing habits while rewarding slow attention. Most importantly, the painting shows how a work can be decorative and rigorous, gentle and modern, humble in subject and ambitious in result. It proves that radical clarity does not require grand themes; a plant on a shelf can carry the full intelligence of color and form.

Conclusion

“Pot of Geraniums” is a compact manifesto. With a potted plant, a few shelves, and three tuned color families, Matisse demonstrates how modern painting can reinvent still life without abandoning recognition or pleasure. Color is used not as garnish but as scaffolding; drawing is performed in paint; light is constructed by neighbors; rhythm replaces ornament. The geranium becomes an emblem of persistence and poise, the studio a stage where humble things become radiant through attention. In front of this canvas, you experience not just a plant, but the act of seeing simplified to its most rewarding essentials.