Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

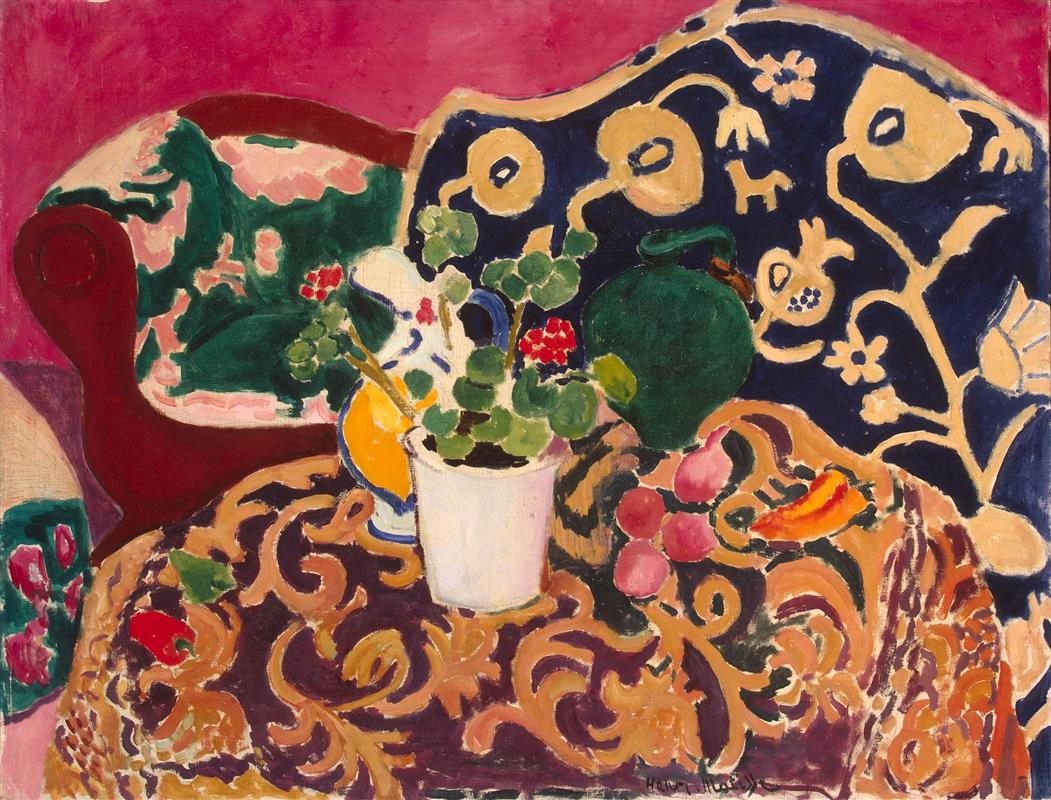

Henri Matisse’s “Spanish Still Life” (1911) transforms a tabletop arrangement into a saturated world of textiles, ceramics, fruit, and floral rhythms. Across a coral-pink interior a carved sofa curves like a theatrical backdrop, its upholstery a dense green garden of pale blossoms. Draped over the right half of the composition, a dark indigo shawl, animated by cream vines and playful motifs, cascades diagonally and meets the fulcrum of the scene: a low round table smothered in an ocher-and-mulberry cloth whose scrolling arabesques ripple like music. Atop this stage sit a white flowerpot of scarlet geraniums, a lemon-yellow jug ringed in blue, a deep green earthenware jar, and a small harvest—pink figs and a flame-orange pepper—nestled into the folds of the cloth. The painting is nominally a still life; in Matisse’s hands it becomes a demonstration that pattern is structure, color is architecture, and ordinary objects can orchestrate an entire visual climate.

A Spanish Echo in the Studio

The “Spanish” in the title refers less to geography than to a vocabulary of materials: mantón-style shawls, embroidered cushions, Moorish arabesques, and glazed pottery that carried the memory of Andalusia into European salons. Matisse does not illustrate Seville or Granada; he distills their sensuous codes into a portable theater of cloth and color. The indigo shawl at upper right behaves like a dancer’s mantle recently cast onto a chair. The tablecloth’s scrolling foliage recalls ceramic ornament expanded into textile. The carved sofa crest and floral upholstery supply a historical counterpoint, grounding the enthusiastic patterns in furniture craftsmanship. Spain, here, is a mode—a way of staging light and rhythm—rather than a place on a map.

Composition Organized by Textiles

The layout is a negotiation among three powerful fabrics and a tight cluster of objects. The sofa sweeps laterally across the upper register, a soft horizon that stabilizes the room. The blue shawl tumbles diagonally from the upper edge to the tabletop, cutting across the picture and energizing the right side with large, creamy motifs that read almost as calligraphy. The tablecloth, pushed close to the picture plane, presents an oval stage whose patterned surface contains the still life and draws the viewer forward. Within this lattice of fabric, the pot, jugs, fruit, and flowers sit slightly off-center, giving the composition a breathing asymmetry. Matisse balances horizontal calm, diagonal thrust, and circular concentration so that the eye glides, turns, and lingers without strain.

Color Architecture and Climatic Chords

The painting’s architecture is chromatic. A warm coral field unifies wall and floor into a single climate that never retreats into neutrality. Against this warmth, two cool families do the major work: a deep garden green saturates the sofa and earthen jar, while an indigo-to-navy range dominates the shawl. Interleaved throughout are high-key accents that act like lights: the lemon wedge of the pitcher’s belly blazes at the table’s edge; the white flowerpot holds a column of clarity at the center; the geraniums spark red notes that resonate with the coral ground; and the figs’ dusty pinks soften the cloth’s darker mulberry passages. Because Matisse keeps the palette tight—coral, green, blue, with a handful of bright accents—the relations between neighbors rather than theatrical shadow produce the sensation of light.

Pattern as Structure, Not Ornament

Matisse treats pattern as a load-bearing element. Each textile operates at a different scale: the sofa’s upholstery repeats blossoms in mid-sized units that read as a continuous garden; the tablecloth condenses its motif into tight arabesques, a woven river of ocher that ripples over the tabletop; the shawl on the right uses giant cream motifs—buds, animals, and looping stems—that almost become abstract signs. This scale variety prevents monotony and distributes attention evenly across the surface. Importantly, Matisse leaves slender reserves—thin breaths of undercolor—between patterns and adjacent fields. Those little halos keep the surface alive, prevent muddiness, and make the edges hum.

The Still Life as Conductor

The objects on the table do not dominate by size; they conduct by connection. The white pot is a pause—an area of visual rest—allowing surrounding patterns to crescendo without confusion. Its geraniums gather key colors into one bouquet: green leaves converse with the sofa and jar, red blossoms rhyme with the coral wall, and tiny whites echo the pot and shawl motifs. The lemon-yellow pitcher, collared by a cobalt rim, bridges warm and cool families and suggests light pouring from within rather than falling upon it. The dark green jar gives mass and gravity, a compact counterweight to the bright vase. The fruit—soft pink figs and a curved orange pepper—provide organic shapes whose tactile, edible presence tempers the abstraction of pattern. Together, these objects knit the textiles into a single orchestration.

Drawing with the Brush

Contour here is painted, not penciled. The pitcher’s blue rim loops in a single sure stroke; the shawl’s cream vines have the energy of hand-written letters; the sofa’s rolled arm is declared by a handful of curves that expand and contract with pressure. Where one color passes another, Matisse allows slips and overlaps to remain visible. These traces—small halos at edges, a ridge of raised paint where a curl of arabesque turns—are not blemishes. They are records of decisions that let the viewer feel proximity to the painter’s hand. Even in passages of dense pattern, the drawing is clear, musical, and committed.

Light Constructed by Adjacency

Very little conventional modeling appears. The jar does not cast a shadow; the pitcher gleams without a spectrum of reflections; the fruit are rounded by a handful of tonal transitions rather than a full chiaroscuro. Light arises from adjacency. Yellow sings because it is ringed by blue; white glows because it borders saturated greens and indigo; reds warm because they sit inside a cool sea. Where form needs a lift, Matisse adds a single lighter touch—a shortened stroke along the jar’s flank, a pale notch on a fig—rather than a gradient. The result is a picture that reads instantly from afar and repays close looking with eloquent marks.

Depth Without Perspective Tricks

Space in “Spanish Still Life” is a shallow relief. The tabletop tilts steeply to reveal the patterned cloth, compressing space like a stage seen from the front row. The sofa’s back rises as a painted screen rather than receding as measured perspective. The shawl slides forward, its lower edge nearly kissing the fruit. Overlap, scale, and placement do the spatial work: the pot stands before the shawl because it interrupts its edge; the shawl lies behind the fruit because its motif continues uninterrupted beneath them; the sofa is behind all because it passes behind both table and shawl. With so few cues, the mind completes the room while the eye stays on color and rhythm.

A Conversation with Sister Works

This canvas belongs to the same family as “Seville Still Life,” “Harmony in Red,” and “Red Studio,” yet it offers a distinct equilibrium. Where “Harmony in Red” floods the entire room with a commanding hue, “Spanish Still Life” allows the coral climate to share authority with competing pattern kingdoms. Where “Red Studio” reduces objects to outlines and islands in a red sea, this work lets pattern shout, crowd, and then resolve into harmony through the still life’s mediating bouquet and vessels. It also speaks to Matisse’s “goldfish” pictures in which a single vessel organizes a field; here two vessels and a pot perform that role collectively, with fruit as counter-melody.

The Cultural Thread: Spain as Rhythm

The painting’s Spanishness is not a costume change; it is a rhythm of life. The shawl’s bold motifs evoke the mantón de Manila, a garment of performance and celebration; the scrolling tablecloth echoes Andalusian tiles and textiles; the earthen jar suggests the practical clay vessels of a warm climate. By absorbing these elements into his decorative language, Matisse avoids exoticism. He treats Spain as a source of structure and cadence, an inheritance of ornament that modern painting can recompose without nostalgia.

Material Presence and Evidence of Process

Matisse leaves the effort of making visible. The coral field shows varied saturations where underlying passes breathe through; the sofa’s greens display both thin washes and fat strokes; the cream motifs of the shawl ride across indigo in places and sink into it in others, revealing that he painted fast and returned to adjust. The tablecloth’s arabesques show seams where the artist lifted and set down the brush. These evidences of time keep the surface candid. The room’s serenity is not a veneer; it is something discovered through revision and affirmed by leaving traces of the path.

Emotional Climate and Tempo

Despite the abundance of motifs, the painting does not agitate. It breathes at the tempo of a room in late afternoon: warm air, responsive surfaces, objects waiting to be used. The shawl’s sweep slow-dances through the right half; the sofa’s curve reclines; the bouquet lifts just enough to greet. Matisse’s famous desire for art that offers a “soothing, calming influence” is realized here not by removing stimulus, but by tuning stimulus into order. Viewers can rest their eyes on any part of the surface and always find structure guiding them to the next.

Lessons for Seeing and Making

“Spanish Still Life” offers practical counsel. Begin with a climate color that fuses wall and floor. Let textiles carry architecture and vary their scale so pattern itself articulates near and far. Position a still life where lines, colors, and motifs converge; give it a white or light pause so the surrounding complexity has a field to play against. Draw with the brush so edges stay alive. Construct light through neighbors rather than through theatrical shadow. Permit evidence of process to remain; the painting’s humanity depends on those breaths of undercolor and those seams of decision.

Why It Still Feels New

A century later, the work’s modernity persists because its choices are transparent and generous. The palette is limited yet resonant; pattern is not a decorative afterthought but a structural tool; the still life celebrates the ordinary without sentimentality. In a culture that alternates between maximalism and minimalism, Matisse shows how abundance and clarity can coexist. Designers borrow the lesson daily: a single warm field, a few saturated complements, and one or two patterns at varying scales will hold a room and keep it lively.

Conclusion

“Spanish Still Life” converts a tabletop into a complete world. Coral air envelops the scene; green and indigo textiles armature the space; a pot, a pitcher, a jar, and fruit weave the color families together; and brush-drawn contours keep the surface singing. The painting is not merely about objects arranged on cloth; it is about how seeing can be ordered so that pleasure and lucidity become the same experience. In its confident patterns and measured heat, the canvas remains one of Matisse’s clearest proofs that the decorative, when made structural, yields an art of lasting calm and surprising depth.