Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

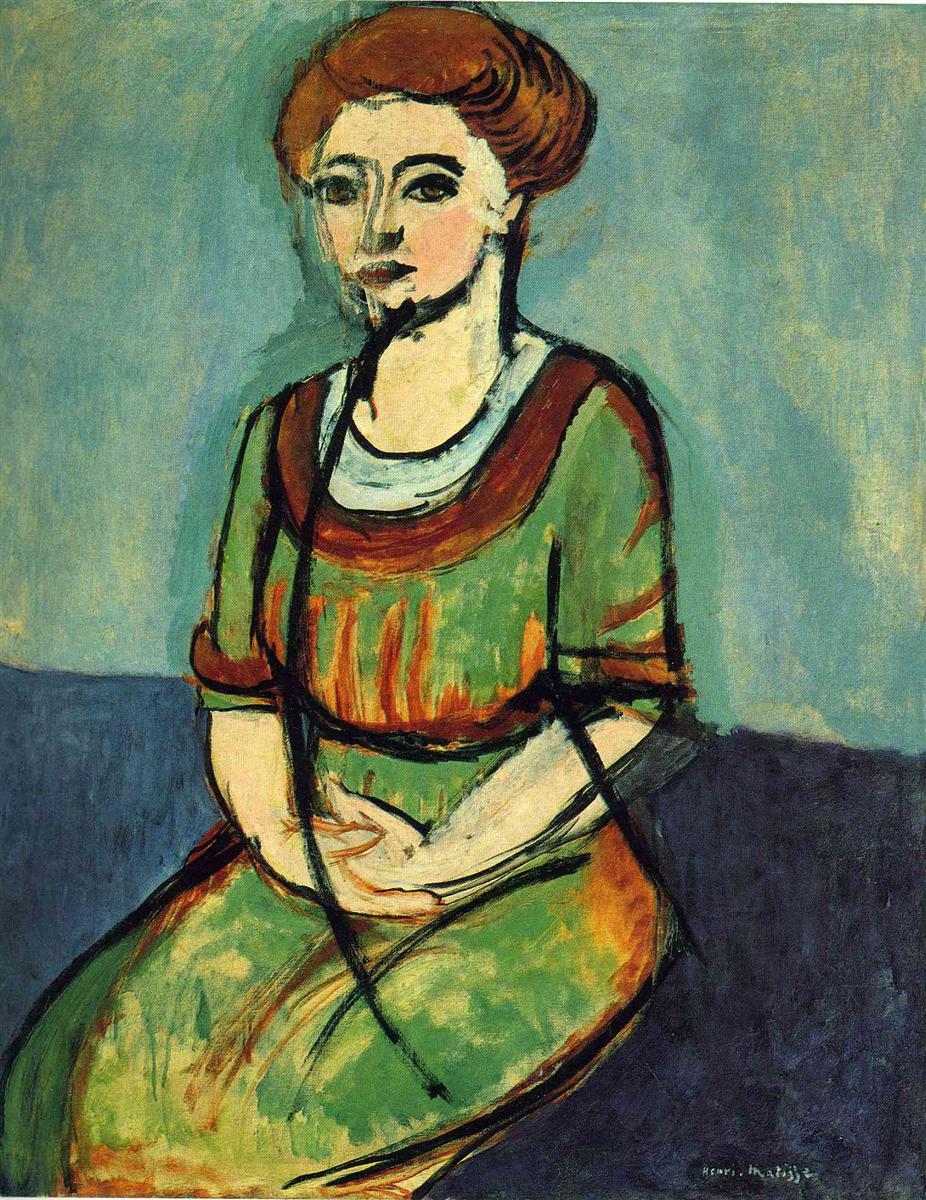

Henri Matisse’s “Olga Merson” (1910) is a concentrated lesson in how a portrait can be both intimate and monumental when built from a small set of decisive moves. A young woman sits in three-quarter view against a two-band backdrop of teal and deep blue. Her auburn hair is swept high; her green dress, warmed by tangerine and ochre notes, falls in simple volumes; her pale hands interlace in her lap. Everything is held together by assertive brush-drawn contours—elastic, black lines that wrap the figure like a calligrapher’s script. The painting belongs to Matisse’s crucial years around 1909–1911, when he channeled the chromatic audacity of Fauvism into a lucid decorative order. Here, hue, line, and flatness replace anecdote; the sitter’s presence is achieved through intervals, not details.

The Moment of 1910 and Matisse’s Orderly Boldness

By 1910 Matisse had moved past the incendiary contrasts of 1905 toward a grammar that prized clarity over shock. He learned to reduce a picture to a few legible planes, to draw with the brush rather than the pencil, and to let color act as structure. “Olga Merson” shows this consolidation in action. The palette is disciplined—teal and ultramarine for the room, sap and apple greens for the dress, terracotta and orange for the hair and collar, a few creams and grays for the blouse and hands, and a near-black contour to declare form. Instead of blending and modeling, he constructs volumes by setting these planes in exact relations. The result is not restraint for its own sake; it is a way to make the portrait read instantly from a distance and deepen at arm’s length.

Composition and the Poise of the Figure

Matisse organizes the rectangle around a stable vertical axis that passes through head, sternum, and clasped hands. The seated body forms a compact pyramid whose base sits on the dark bench and whose apex is the neat coil of hair. The shoulders slant gently; sleeves drop like soft columns; the lap rounds forward with a single, generous curve. Because the background is divided horizontally—cool teal above and a darker blue below—the figure’s silhouette reads with exceptional clarity. The hands anchor the center. They are placed just ahead of the waist, palms meeting like a small oval knot that becomes the portrait’s rhythmic fulcrum. Nothing crowds the figure. Ample negative space around the head and shoulders keeps the composition calm and breathable.

Color Architecture and Climate

The portrait rests on a triad: green, blue, and orange. The dress sets the dominant key in flexible greens, its surface quickened by warm streaks of red-orange that echo hair and collar. Against that green, the teal upper wall and midnight lower band cool and enlarge the space, while the orange notes add warmth and human temperature. Matisse keeps the palette narrow so each relationship is legible. The green of the dress cools markedly near the shaded side; the orange collar flares where it kisses the cool background; the pale blouse and hands brighten simply by adjacency to the surrounding darks. Because hue is doing the work of “light,” the painting holds together without theatrical shadow.

The Calligraphic Contour

Few painters have used the brush-drawn outline with more authority than Matisse, and “Olga Merson” is a masterclass. Contours thicken at the turn of the shoulder, thin across the cheek, and snap decisively along the sleeve and waist. A long, supple line runs from the neck down the bodice and across the lap, simultaneously describing form and binding the dress’s color fields together. Around the head, a dark loop traces hair and jaw, tightening at the chin and easing near the temple to allow the face to breathe. These lines do not fence in color; they energize it, like lead cames making stained glass blaze. Because the contour is so sure, interior modeling can remain minimal without sacrificing presence.

Face and Expression as Planes

Matisse avoids fussy portrait resemblance in favor of a masklike clarity that nonetheless conveys character. The face is organized into a few decisive planes: a cool, slightly greenish half-shadow on the far cheek and forehead; a warmer pink that gathers on the near cheek and lips; a firm, dark drawing of eyelids and brows that gives the gaze its quiet intensity. The mouth is small but not tight; the eyes are almond-shaped, slightly asymmetrical in the living way of a face; the nose is built from two strokes and a small wedge of shadow. The expression is reserved, self-possessed, and alert—dignity without theater. Because the head tilts a fraction toward the viewer’s left, the portrait escapes static frontality while preserving poise.

Hands, Lap, and the Center of Gravity

The interlaced hands are the painting’s heartbeat. Their pale color, nearly the lightest in the image, signals delicacy; their simplified drawing—fingers indicated by a few joined bends—avoids anatomical fuss. They sit in a pocket of light fabric that Matisse leaves almost unmodeled, a reserve that reads as a white scarf or apron fold. The looping black lines that fall from the shoulders cross near the hands, forming a visual knot that draws the eye into the image’s center. That knot is not decoration; it is a structural device that keeps the large green planes synchronized and balances the weight of the head’s warm color above.

The Dress as Architecture

What appears at first as a garment quickly reveals itself as the picture’s scaffolding. The green dress is divided into zones by dark seams and by the sash that cinches the waist. Within each zone, Matisse lays broad, directional strokes that follow the imagined weight of fabric: downward pulls along the skirt, lateral sweeps across the bodice, short hatches at the sleeve. Occasional flares of orange and ochre run through the green like heat shimmering in cloth. These are not descriptive patterns but structural rhythms; they prevent the broad color fields from going inert and keep the surface alive at every distance.

Background as Active Field

The teal wall and the midnight bench are not neutral fillers. The upper field is brushed thinly, allowing hints of the underlayer to breathe through, and its strokes move in soft, lateral eddies. This activity sets up a gentle counter-rhythm to the vertical figure. The lower band, darker and cooler, presses up against the sitter like a quiet bass note. Together, these fields perform the space-making Matisse desires while preserving flatness. The world behind Olga is a plane, not a tunnel; the portrait is a relief, not a peek into a room.

Light Constructed by Adjacency

There is almost no traditional chiaroscuro. The sense of light arrives from color neighbors. The face appears luminous because warm cheek meets cool temple and is framed by dark hair. The blouse glows because its pale grays and creams are bounded by the deeper green of the dress and the black lines that clarify edges. The hands read as soft because they sit on a cushion of white fabric and are encircled by the dress’s darker folds. Even the hair shines thanks to small shifts from burnt orange to warm brown set against the cool teal sky of the wall. Light is not documented; it is built.

Brushwork and the Evidence of Process

One of the pleasures of this canvas is how openly it shows its making. In the dress, loaded strokes slide and leave ridges that catch incidental light; at the shoulders, one can see earlier placements where Matisse adjusted the angle and left a faint halo; along the contour of the cheek, a thinner pass allows the background to flicker through. These traces do not register as indecision. They read as the record of arriving at rightness—proof that the portrait’s calm was discovered, not prepackaged.

Ornament as Discipline

Matisse often called his art “decorative,” a term he used not to mean fussy prettiness but the even distribution of interest across a surface. In “Olga Merson” the decorative principle is expressed sparingly and structurally. The red-brown collar repeats the hair’s temperature and provides a measured accent near the face. The dark sash and seams act as graphic rhythms that prevent the dress from becoming a blank slab. A few subtle loops of black line fall like cords from the shoulders, crossing and re-entering the fabric to create an elegant lattice. Nothing is superfluous; everything has a job in the overall harmony.

Psychological Temperature and Human Nearness

The portrait’s mood is warm but not sentimental. The limited palette and shallow space create a contemplative stillness; the sitter’s slight lean and interlaced hands signal inner composure. Although the features are generalized, the person feels present. Matisse achieves this by calibrating the language of signs—the tilt of the head, the play between warm and cool on the face, the pressure of the hands—and by keeping the paint close to the body’s scale. The overall effect is respect. Olga occupies the painting with dignity, neither absorbed into pattern nor weighed down by narrative.

Relations to Sister Works of 1909–1911

Placed beside portraits such as “Girl with a Black Cat,” “Girl with Tulips,” and “Greta Moll,” this canvas shows the family traits of Matisse’s 1910 clarity: large fields of high but stable color; dominant, brush-drawn contour; and shallow, stage-like space. Compared with the slightly earlier 1908 portraits, “Olga Merson” is less explosive in chroma but more architectonic in design. It also anticipates the Nice interiors of the 1920s, where women, textiles, and flowers inhabit rooms of balanced color climates. Here, the architecture is already present—the figure reads as a decorative panel without surrendering human specificity.

Classical Echoes and Modern Flatness

Matisse engages the tradition of the seated female portrait while reimagining it through modern flatness. There is a quiet echo of Renaissance triangular composition and of the classical bust’s clarity. Yet every traditional illusion—deep room, carefully modeled flesh, detailed costume—is pared away. Flat color planes, emphatic outline, and simplified anatomy replace mimetic description. This balance of echo and innovation gives the painting its timelessness: the sitter seems both of her moment and outside of it.

The Ethics of Simplification

Simplification, for Matisse, is an ethic of care. By removing furniture, paraphernalia, and lifelike texture, he avoids turning the sitter into a pretext for virtuoso display. Instead, he presents a clear arrangement of intervals that allows the viewer to experience calm, order, and warmth. The subject is not overwhelmed; the viewer is not distracted. “Olga Merson” demonstrates how an artist can honor a person by giving form to the essentials of their presence, not the taxonomy of their appearance.

Reading the Surface Like a Score

One can “listen” to this picture the way one listens to a piece of chamber music. The large color fields supply the key; black contours keep time; accents—the collar, the lips, the bright knuckles—are small percussive strikes; the hands offer a gentle cadenza at the center; the turn of the head resolves the phrase in a final, poised chord. This musical reading explains why the portrait remains engaging despite its economy: the eye moves at a comfortable tempo, always finding a relation to confirm or a subtle difference to savor.

What the Portrait Teaches About Seeing

“Olga Merson” proposes a method any image-maker can adopt. Begin with a few large planes that set the climate. Draw with the brush so that line carries structure and spirit. Construct light through adjacency rather than through heavy shadow. Allow some evidence of process to remain visible so the surface breathes. Use ornament sparingly and only to stabilize the whole. Above all, trust that clarity of relation—between warm and cool, contour and plane, large and small—can convey more humanity than a crowded inventory of details.

Enduring Freshness

More than a century later, the portrait feels fresh because its decisions are permanent. Green against blue still reads as air and cloth; orange remains a universal warmth of face and hair; black contour continues to feel like a living line. The painting’s humanity is large-minded: it does not pry into biography or private drama; it presents a person as a poised presence within a balanced world. That generosity is why the image continues to meet contemporary eyes with ease.

Conclusion

Henri Matisse’s “Olga Merson” transforms a seated woman into a durable architecture of color and line. A small number of hues—the blues of the room, the greens of the dress, the oranges of hair and collar—are orchestrated with elastic black contours into a surface that is at once calm and vibrant. Space is shallow, light is constructed, brushwork is candid, and the rhythms of seam, sash, and hand keep the eye engaged without strain. The portrait embodies Matisse’s 1910 promise: that painting can be clear, decorative, and deeply human at the same time. In its serene equilibrium, the canvas invites us to look slowly, to trust essentials, and to recognize presence in the choreography of a few exact relations.