Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

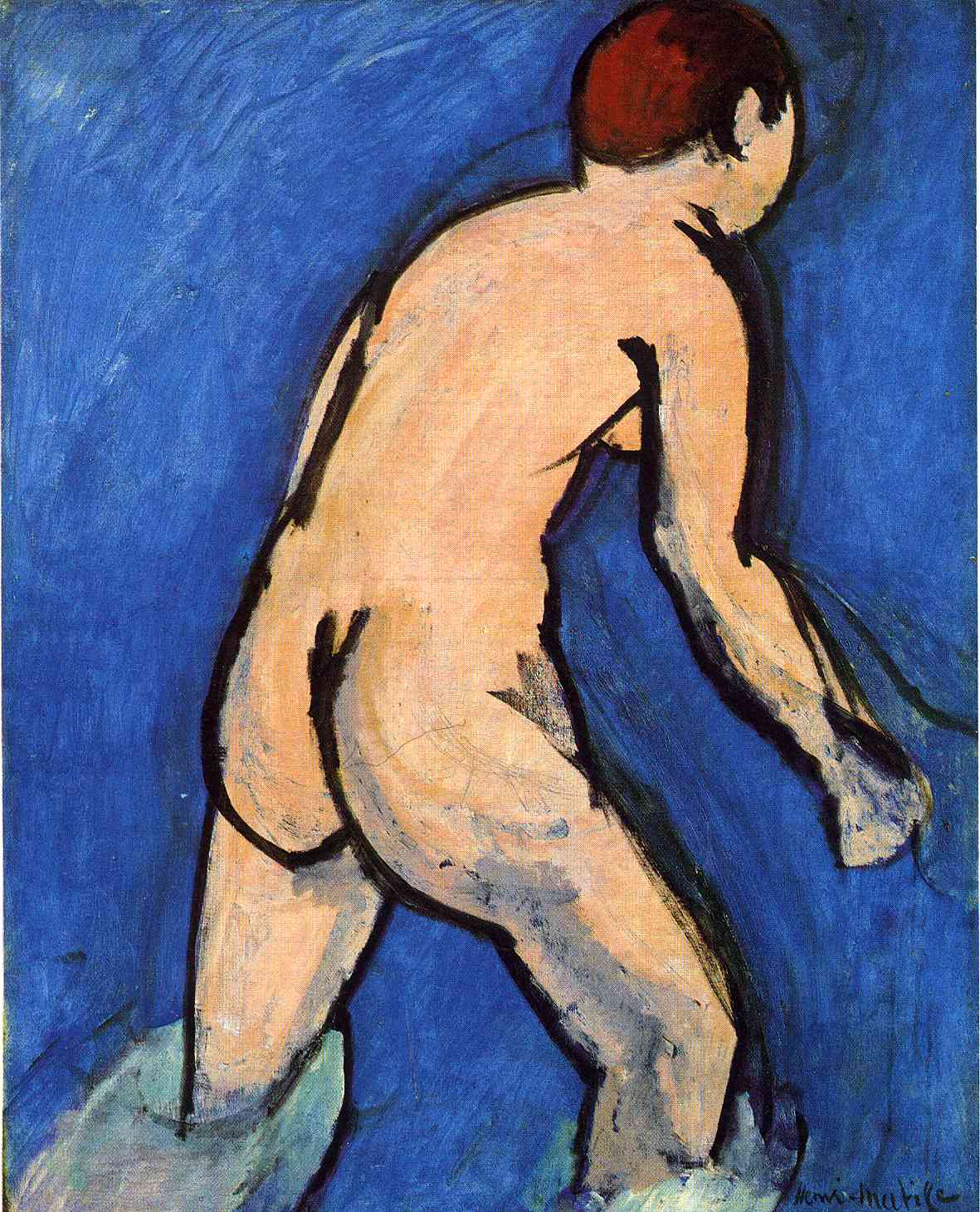

Henri Matisse’s “Bather” (1909) compresses a whole philosophy of painting into a single figure stepping into water. A nude seen from behind advances across a plane of saturated blue, ankle-deep in foam. There is no horizon, no anecdotal shore, no descriptive background—only the relationship between warm flesh and cool blue, conducted by bold, brush-drawn contour. The body is simplified to essential planes; the sea is an enveloping field rather than a place; and motion is conveyed through the torque of shoulder, hip, and stride. In a few decisions—palette, silhouette, brushwork—Matisse transforms the venerable theme of the bather into a modern emblem of clarity and presence.

The 1909 Pivot Toward Order

By 1909, Matisse had moved beyond the flamboyant clashes of early Fauvism toward a calmer, architectonic language. He was testing how far color could carry structure without the crutch of descriptive modeling. “Bather” belongs to this turning point alongside “Dance,” “Music,” and a series of coastal nudes and studio still lifes. The program was consistent: limit the palette, flatten space, draw with the brush, and orchestrate large planes so the painting reads instantly at distance and deepens up close. Instead of using color to shock, he uses it to build a durable order—a harmony that can hold movement and serenity at once.

Composition as a Single, Sweeping Gesture

The composition is disarmingly simple: a three-quarter back view of a figure in midstep fills the surface, tilted diagonally so that shoulder and heel pull in opposite directions. The left leg plunges into foamy water at the lower edge; the right leg lifts forward with the knee flexed; the right arm bends and compacts, while the left arm extends down like a counterweight. This arrangement creates a powerful S-curve from crown to heel. The figure’s mass is nudged off-center toward the right edge so that the expanse of blue at left feels like open sea—space into which the bather is moving. There are no small distractions. Every proportion serves the swing of the stride and the intimacy of proximity: we stand so close behind the figure that we can almost feel the splash.

A Triad of Color That Creates Climate

The palette operates like a chord: ultramarine blue for the water/air field, warm apricot and ochre for skin, and deep, almost charcoal-black lines to declare form. A small russet cap of hair completes the triad. Because colors are few and saturated, relationships become the drama. The blue field cools and expands the picture; the flesh warms and advances; the dark contour stabilizes their meeting. Matisse subtly modulates within each zone—thin veils of lighter blue sweep across the ground; flesh cools near shadowed edges; foam is a jostle of pale greenish whites—yet he never loses the legibility of the main triad. The result is a climate rather than a scene: blue as atmosphere, flesh as warmth, dark line as structure.

Contour as the Primary Architecture

Matisse draws with the brush. Contours are laid in as continuous, elastic bands that thicken at joints, thin along taut surfaces, and hook decisively at the knee, elbow, and heel. These lines function like the lead cames in stained glass: they hold planes in tension while letting color blaze. Because the contour is so sure, interior modeling can be minimal. A few slants of gray at the shoulder blade, a cooler wedge in the gluteal fold, a violet-brown notch beneath the arm—these brief notes are enough for the mind to complete volume. The figure convinces not through shaded gradations but through the inevitability of its outline and the rightness of interval.

Brushwork and the Living Surface

The surface breathes. In the blue ground, long, slanting strokes move like currents under light wind, leaving faint ridges that catch illumination and keep the plane from freezing. Within the flesh, paint sits creamier; strokes overlap like facets, especially along the back and thigh, where one warm note presses against another cooler one. At the ankles, quick, broken dabs shape the churn of foam. Around the contour, Matisse allows small haloes—thin margins where dark line, flesh color, and blue meet—to remain visible. They are the record of looking and adjusting: the painter arrives at rightness in paint rather than erasing his process.

Space Without Horizon

Traditional bathers stand within elaborated landscapes: shoreline, distant hills, a clear horizon. Here, space is a shallow stage made from a single field of blue. The only cues to depth are overlap (foam over ankle), the scale of the figure (monumental, cropped), and the way the blue darkens slightly near the lower edge as if deepening. This deliberate suppression of perspective brings the bather forward into our space, turning the painting from a window into a relief. It also fuses sea and sky—blue becomes both water and air—so that the body appears to move into an elemental continuum.

Light Built by Adjacency

There is no theatrical spotlight and hardly any cast shadow. Light is constructed by adjacency and temperature. Flesh appears luminous because it sits against saturated blue and is bordered by dark line; foam reads bright because its pale strokes interrupt the blue while catching bits of flesh color nearby; the head turns because a small russet cap meets the dark contour and a cooler wedge at the jaw. Matisse places highlights, he does not blend them: a touch along the shoulder blade, a flare on the thigh, a paler lick at the calf. These are enough to animate the planes without dissolving the surface into modeling.

Gesture and the Feeling of Motion

The painting’s motion is bodily, not anecdotal. You sense the weight shift: the left leg planted in foamy resistance, the right leg driving forward. The turn of the neck suggests attention to the path ahead. Because the back is presented so strongly, the viewer’s empathy is physical—we almost lean with the figure. The raised shoulder and tucked arm tighten the torso; the forward knee loosens it again. This push-pull generates the sensation of stepping into cold water: hesitation and resolve in the same instant.

The Bather Tradition, Reimagined

From Titian to Courbet to Cézanne, the bather is an art-historical constant. Matisse honors the tradition while discarding its storytelling scaffolding. There is no myth, no allegory, no social anecdote. The body is not an object for display but the architecture of the picture itself. By choosing the three-quarter back view, he avoids the conventions of the frontal or Venus-like nude and instead emphasizes musculature, movement, and the relation of body to surrounding field. The painting becomes a modern classicism: the timelessness of bathing rendered with the direct means of color and contour.

Relation to Sister Works of 1909

“Bather” is in close conversation with “Naked by the Sea,” “Nude in Sunlit Landscape,” and the panels “Dance” and “Music.” All rely on a shallow stage, a limited palette, and figures simplified into legible silhouettes. Where “Dance” turns bodies into a communal ring against blue and green, “Bather” isolates a single figure in a similar climate to test what one body can do to a plane. Compared with the earlier “Blue Nude” (1907), whose sculptural thrust and angularity shocked audiences, this 1909 figure is gentler, more rhythmic, its energy distributed through the stride rather than through exaggerated recession. The continuity across these works is the conviction that clarity is not the enemy of depth but its precondition.

The Decorative Principle at Work

When Matisse calls his art “decorative,” he means that every inch of surface participates in an ordered rhythm. In “Bather,” the even, animated blue carries the eye without dead zones; the contour provides a steady beat; the foam and hair introduce small syncopations; and the broad flesh planes operate like chords within the field. Decoration here is discipline, not frill. It ensures that the painting holds together at a glance and that the figure belongs to its climate rather than sitting on top of it.

Psychological Temperature

Though we cannot see the bather’s face, the painting has a mood: alert, restorative, and unhurried. The posture is purposeful but not strained; the stride is strong but not urgent. The sea is not threatening—it is a welcoming medium, a surface ready to yield. Because the figure is monumental and near, the image feels intimate without being invasive. The lack of anecdote protects dignity: this is not voyeurism; it is kinesthetic empathy.

Material Scale and Proximity

Scale matters. The figure is large enough that the contour’s changes of pressure read as physiological rather than calligraphic; the color planes are broad enough to carry subtle temperature shifts. The crop at top and sides increases proximity, as if we had approached too close to fit the whole body in view. That closeness sets the viewer in the same space as the bather, pressing against the blue field rather than peering at a distant shore.

The Red Hair Note and the Logic of Accents

The small cap of russet hair might seem incidental, but it plays a precise role. It warms the highest point of the figure, echoing the flesh while resisting dissolution into the blue. It also sets a tiny counterpoint to the foam’s pale accents at the ankles. These two far-apart notes—rust at the crown, white-green at the feet—bookend the body and reinforce the vertical sweep of the stride. In Matisse’s language, accents matter because the grammar is spare; each must earn its place.

Evidence of Process and Honest Surface

“Matisse the editor” is visible in the paint. There are places where a contour doubles, suggesting the hip was shifted; a thin veil of blue overlays an earlier pass, deepening the field; light scrapes reveal the canvas tooth beneath a flesh tone. Rather than polishing these signs away, he lets them stay, trusting that viewers will feel the authority of a resolution reached through adjustment. The painting’s calm is not sterile; it is the outcome of listening to the surface as choices accrue.

The Blue Field as Element and Idea

Why an all-over blue? Practically, it isolates the body and collapses sea and sky into one element. Emotionally, it creates a cool, stabilizing climate that tempers the warmth of flesh and the energy of motion. Conceptually, it turns the background into an idea: water as the ground of being, a field into which the human form enters and with which it harmonizes. The blue is not merely the setting; it is the partner in a duet.

Lightness Through Simplification

One of the marvels of “Bather” is how light the figure feels despite its mass. Simplification makes it buoyant. There are no heavy shadows to pin the body down, no deep space to pull it away; instead, the painting relies on clean relations that keep forms floating on the surface. This lightness is not decorative sweetness. It is a modern ethic that resists narrative burden and lets the eye rest in essentials—line, color, and rhythm.

Lessons for Seeing and Making

“Bather” models a method adaptable across visual fields: choose a strong triad of colors; set a single dominating field; draw with decisive contour; model by planar adjacency rather than lurid shading; and build space shallow so the surface remains alive. The result is an image that reads instantly, holds together at every distance, and invites the viewer’s body to echo the motion depicted.

Enduring Resonance

Over a century later, the painting feels fresh because it does not rely on fashion or detail. Its force comes from decisions that remain legible: where the contour tightens and releases, how blue meets flesh, why a highlight belongs exactly where it is. Viewers recognize themselves in the stride and the pause at cold water’s edge; makers recognize a grammar of economy that still instructs. The bather steps forward endlessly, carrying modern painting’s promise of clarity with her.

Conclusion

“Bather” distills Matisse’s 1909 ambitions into one moving figure and one continuous blue. Color makes climate, contour makes structure, brushwork keeps the surface breathing, and space becomes a shallow stage where human motion reads with timeless immediacy. The painting renews an ancient theme not by embellishment but by concentration. It asks very little of representation and gives very much in return: a sensation of stride and splash, warmth against coolness, and a serene belief that art can be built from the fewest necessary means and still feel fully alive.