Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

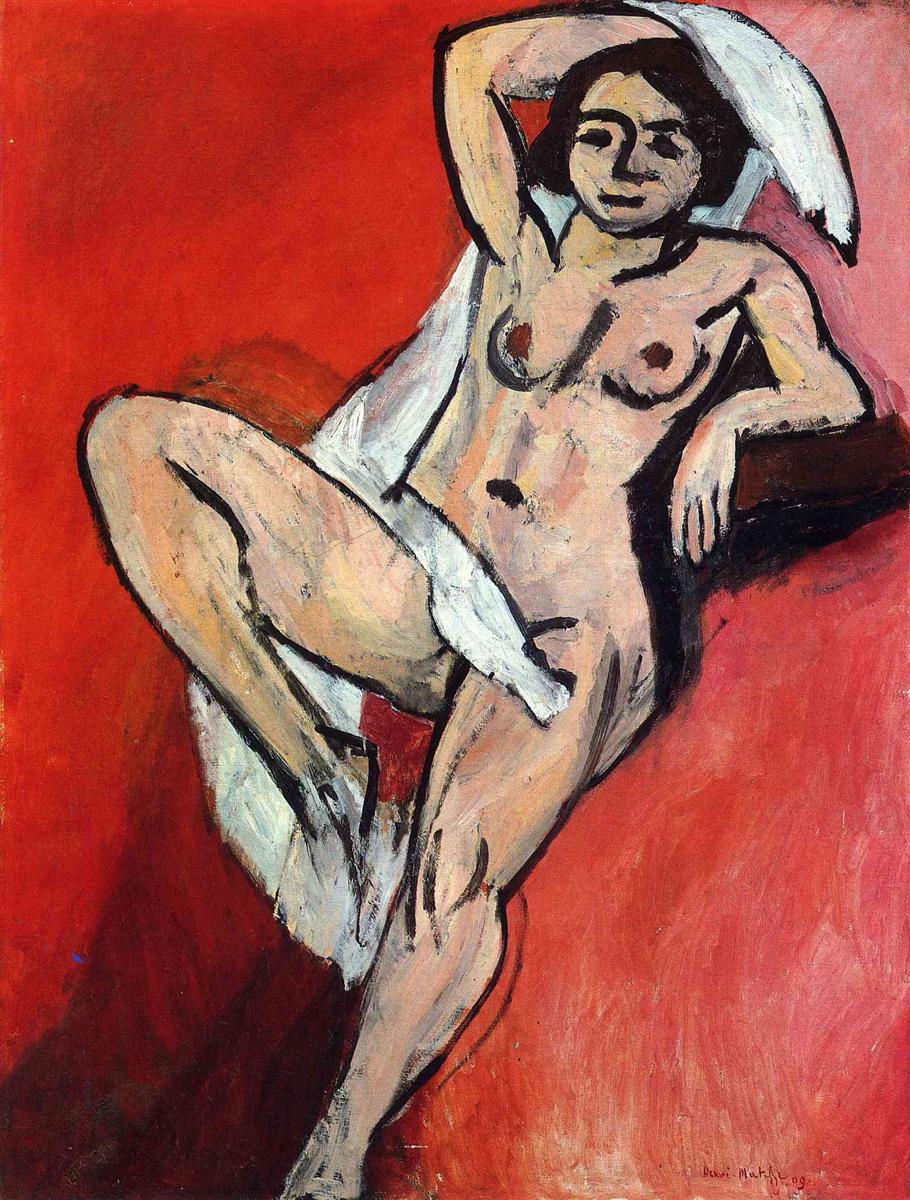

Henri Matisse’s “Nude with a Scarf” (1909) is a luminous demonstration of how a body, a single garment, and a field of color can become an architecture of feeling. A reclining woman occupies nearly the whole canvas, her limbs forming diagonals that slice through a saturated red ground. A pale scarf—more shape than textile—arcs over her head and cuts across hip and thigh in cool flashes. Heavy, brush-drawn contours declare each turn of form. Nothing is anecdotal; the room has dissolved into a hot atmosphere in which figure and color are the true subjects. What begins as a studio nude resolves into a manifesto about the power of simplification: color builds climate, line conducts rhythm, and a few planes of paint can carry the weight of presence.

A 1909 Turning Point

The year 1909 marks Matisse’s passage from the incendiary clashes of Fauvism toward a calmer order that would culminate in the great panels “Dance” and “Music.” The insight was not to abandon high color, but to harness it. “Nude with a Scarf” belongs to this moment of consolidation. The palette is limited yet intense, the drawing is performed with the brush, and the background is a continuous field rather than an illusionistic room. The painting displays Matisse’s new grammar: strong silhouettes, shallow space, planar modeling, and a climate determined by large, resonant chords of hue. It is both an afterglow of Fauvism and a preface to the monumental clarity of 1910.

First Encounter: A Red Climate

The first sensation is red—everywhere. The ground is not a backdrop but a climate, a warm pressure that wraps the body. Its saturation varies in broad zones: deeper at the lower left, lighter at the upper right, with visible drags of brush that keep the plane from going inert. Because the red is so dominant, the cooler notes—the scarf’s whites and pale grays, small reserves of flesh lit by light pink—read with extraordinary brightness. Matisse’s decision to bathe the scene in one color turns the nude into a chord rather than a figure on furniture. Red becomes air, heat, and stage in one.

Composition: Diagonals and the Open Triangle

The figure arranges itself into diagonals that animate the rectangle. The left leg shoots upward; the right leg bends toward the lower margin; the torso tilts; the left arm arcs above the head, meeting the scarf in a long curve. These angled thrusts create a loose triangular scaffold open toward the lower left corner, which keeps the composition from locking into static repose. The body is pivoted around the right hip; that fulcrum presses into the edge of a dark platform—a minimal cue that grounds the pose without building a full interior. Across this geometry, the scarf moves like a counter-melody, softening edges and inserting cool pauses into the red continuum.

The Scarf as Structural Device

Calling the cloth a scarf under-describes its function. It is a compositional instrument: a wedge that separates head from ground, a band that clarifies the arm’s arc, a pale fracture across the pelvis that rearticulates light, and a sequence of cool accents that keep the red climate breathable. The scarf’s edges are not fussed; they are cut with confident strokes that leave small haloes where white slides over red. In several places, the cloth creates pockets of negative space—between arm and head, thigh and torso—turning absence into form. It is both garment and geometry.

Contour as Conductor

Matisse draws with paint. Heavy, near-black contours wrap the body, their pressure changing as form turns. At a shoulder the line thickens; along the flank it thins; around the knee it hooks decisively. These outlines do not imprison the color; they energize it, like lead cames that make stained glass blaze. Because the contour is so authoritative, interior modeling can remain minimal. A few slashes of gray or warm brown inside the thigh, a pale bar across the ribcage, a darker notch at the navel—these are enough to cue volume. The rest is the mind’s work, guided by the line’s inevitability.

Color Architecture: A Three-Part Chord

The painting is built on a chord of three families: the red field, the warm flesh, and the cool whites of the scarf. Red supplies climate and depth; flesh warms into the field without dissolving; white cuts through as air. Small additions tune the chord: charcoal-violet in the contour; dull brown in the platform; soft pink lights on breast and cheek. Because there are so few notes, every relation is legible. A pale highlight reads as luminous not because it is bright in isolation, but because it is placed against a saturated neighbor. Matisse composes with adjacency, not with a catalog of local colors.

Light Without Chiaroscuro

No theatrical spotlight governs the scene. Light is constructed by neighbors and by the weight of the red. The body appears luminous because warm flesh sits within a sea of red and is rimmed by dark contour; the scarf gleams because a white plane is set against temperatures on both sides; the platform feels solid because its dark brown absorbs the surrounding heat. A few deliberate highlights—the arc along the shin, a soft cap on the knee, a touch on the cheek—finish the effect. Matisse’s light is a consequence of structure, not an overlay.

Space as a Shallow Stage

The room has collapsed; space is a shallow stage. The platform’s edge, the figure’s overlap, and the direction of the brushwork do the little spatial work required. This shallowness protects the painting’s surface from illusionistic tunneling and keeps attention on the choreography of color and line. The reclining body does not recede into depth; it presses forward into the viewer’s space, a modern counterpart to classical relief.

Brushwork and the Living Surface

“Painterly” is not a garnish here; it is meaning. In the red field, long, slanting strokes move like currents. Around the head, the brush slows and thickens, creating a halo where red and white meet. Within the flesh, broader, creamy passages sit beside thinner scrapes that allow the ground to flicker through, producing a vibration akin to sunlight on skin. At a few edges, earlier placements remain as ghosts—a shoulder shifted, a knee tightened—leaving a record of arriving at rightness. The canvas shows its own time.

Anatomy Simplified to Planes

Matisse refuses descriptive anatomy in favor of planar clarity. The knee is a faceted volume made of two or three tones; the breast is a gathered oval nudged forward with one warm note; the abdomen turns with a single wedge of gray. Because the drawing is so exact, this spareness reads as truth rather than omission. The viewer experiences a whole body, not a list of muscles. It is a modern classicism: sculptural presence achieved through the fewest sufficient planes.

Gesture and the Mood of Ease

The nude’s expression is quiet, the mouth set in a small, knowing curve; the eyes are simplified yet direct. The lifted arm is not a theatrical flourish but a gesture of ease. The left leg’s upward angle brings the pose to the verge of action without breaking rest. The body is not being displayed; it is at home in its climate. This balance—poised yet relaxed—carries the psychological weight of the picture. The red ground could have turned the scene feverish; the sitter’s self-possession cools it into warmth rather than heat.

The Decorative Order, Reimagined

Matisse’s “decorative” is a principle of coherence, not ornament for ornament’s sake. In this canvas it means that every inch of surface belongs to one system. The red field distributes attention evenly; the scarf repeats its pale note in several locations; contour provides a constant beat; and the figure’s diagonals interlock with the rectangle’s edges so that no zone is accidental. The painting has the unity of a patterned textile while preserving a human core.

Dialogue with Sister Works

Seen alongside the “Blue Nude” (1907), this painting softens the earlier sculpture-like thrust into a more lyrical recline. It shares with “Harmony in Red” the courage to saturate a field with a single color, turning environment into atmosphere. And it participates in the same structural economy that will underwrite “Dance” and “Music”: few colors, big planes, decisive edges. Where those panels convert bodies into archetypal signs, “Nude with a Scarf” keeps intimacy intact, a human scale version of the larger program.

The Ethics of Simplification

Simplification here is not a shortcut; it is a moral and aesthetic stance. By removing furniture, props, and anecdote, Matisse shields the sitter from spectacle and emphasizes relation over detail. The body is not a pretext for virtuoso description; it is a measure of intervals, a rhythm among fields. Viewers are invited to feel balance, not to inventory parts. This restraint is part of the painting’s dignity.

Material Evidence and the Trace of Process

One of the painting’s pleasures is how openly it shows its making. The scarf’s white drags into red, turning edges rosy; the contour doubles at a calf where a decision shifted; a brown underlayer hums beneath a pale thigh. These remnants do not weaken the final calm; they enrich it. You sense the painter thinking in paint, not applying a plan, and the completed harmony carries the authority of choices resolved in situ.

The Red Ground as Emotional Engine

Why red? Beyond art-historical echoes, the answer is experiential. Red compresses space, warms flesh, and makes cool notes blaze. It accelerates the eye while making pauses—like the scarf’s whites—feel refreshing. It also strips the scene of domestic specificity; red is not a sofa or a sheet but an emotional weather. The body becomes a form of heat within heat, and the small darks of hair, contour, and platform read as grounding embers. Few colors make a stronger case for Matisse’s belief that color itself can be the carrier of feeling.

Modern Classicism and Timeless Poise

The nude has been a constant in Western art, often draped in stories to justify its presence. Here, story evaporates, leaving an essential pose rendered with modern means. The figure’s monumental calm—achieved without marble weight, achieved with color and line—connects the painting to the classical tradition even as its surface proclaims the twentieth century. The scarf—a gesture of modesty and design—humanizes the archetype. The result is both timeless and unmistakably of 1909.

Lessons for Seeing Today

The canvas offers a durable method for image-making: reduce elements; make color do structural work; draw with the brush; model with planes; keep a shallow stage; let a few accents carry light. Designers, photographers, and painters alike can read it as a primer. Its clarity is not minimalism for its own sake; it is maximum expressiveness with minimum means. That approach is why the painting still reads as fresh.

Conclusion

“Nude with a Scarf” compresses Matisse’s 1909 discoveries into a single, breathing image: a red climate, a poised body, a cool arc of cloth, and a web of bold contours that hold everything in place. Space is shallow; light is relational; brushwork remains visible; and every mark does structural work. In refusing excess and trusting essentials, Matisse transforms a studio pose into a lasting form—an image of warmth, poise, and modern grace that continues to instruct the eye on how little is needed for a figure to feel fully present.