Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

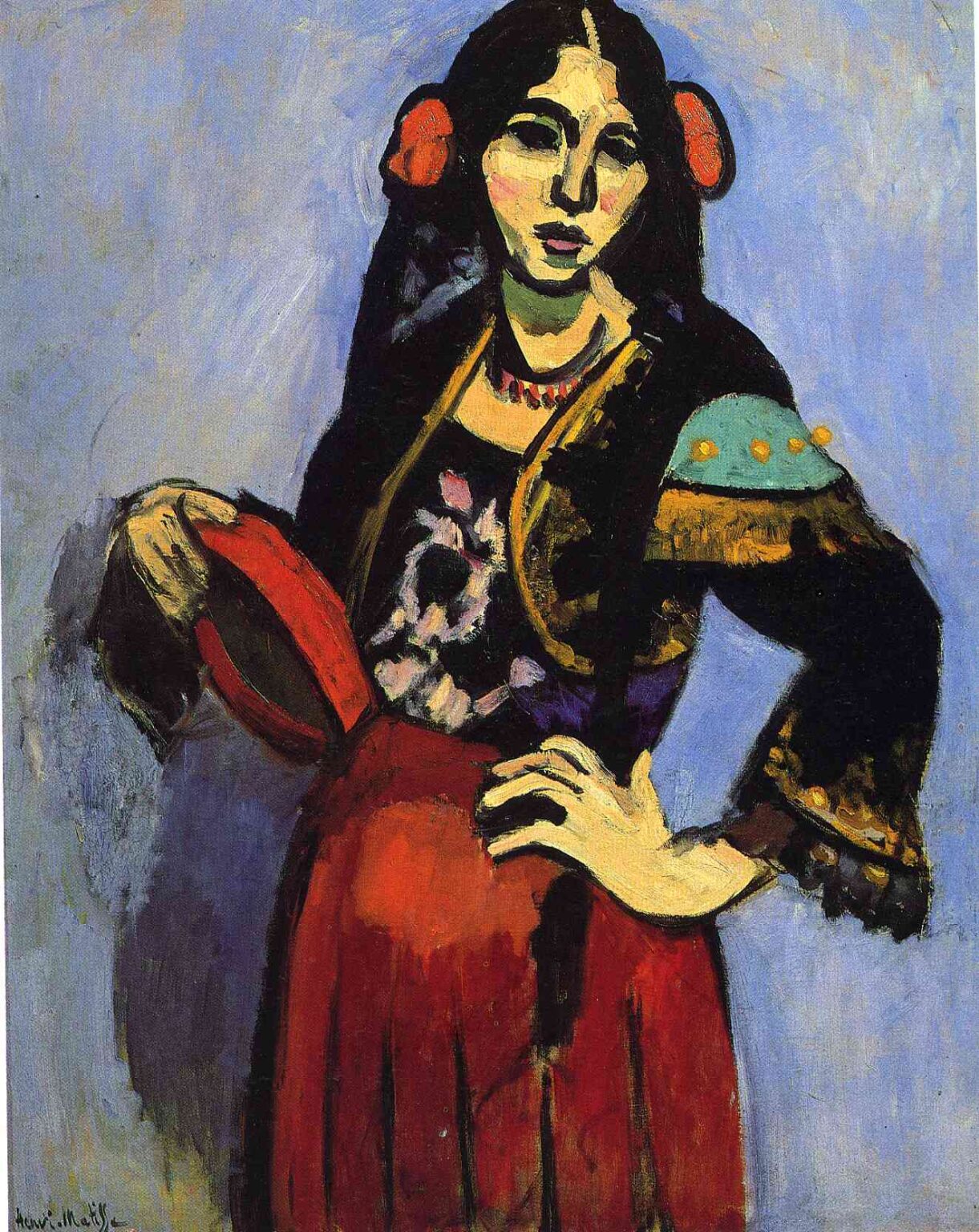

Henri Matisse’s “Spanish Woman with a Tamborine” (1909) turns a single figure into a compact theater of color, rhythm, and character. A woman stands against a cool, unbroken blue field. Her black jacket is netted with gold edging, a turquoise shoulder patch studded with yellow dots, a red necklace circles her throat, crimson rosettes pin back her hair, and a heavy red skirt falls from her waist. One hand fixes at the hip, the other lifts a scarlet tamborine, and the face—framed by long dark hair—meets the viewer with lucid, steady intelligence. Nothing here relies on anecdote. The painting’s authority comes from Matisse’s economy: broad planes, declarative contours, and a palette that strikes a few strong notes and lets them ring.

A 1909 Language of Clarity

The year 1909 stands at the hinge of Matisse’s early career. The incendiary clashes of Fauvism had already liberated color from description; the task now was to harness that freedom to an enduring order. Paintings from this period share certain traits: legible silhouettes; limited palettes tuned to harmony rather than shock; drawing performed by the brush; and backgrounds treated as unified fields rather than staged interiors. “Spanish Woman with a Tamborine” belongs squarely to this consolidation. It is a portrait that behaves like an emblem, a figure that reads at a distance as a single, rhythmic sign and up close as a living surface of decisions.

Composition and the Poise of the Figure

Matisse builds the composition around a pyramid whose apex is the crown of the head and whose base runs across the hem of the red skirt. The left arm, lifted with the tamborine, creates a diagonal counter to the strong verticals of torso and jacket. The right arm fixes on the hip, placing the hand in the heart of the picture where pale flesh meets the black sleeve and the red skirt—a small crossroads that quietly becomes the composition’s fulcrum. Because the background is a continuous plane of blue, the figure’s silhouette reads with immediate clarity. Tilt, counter-tilt, and the circular tamborine generate a choreography that is at once stately and dynamic.

Color Architecture and the Climate of the Painting

Color carries structure. The blue ground is a cool sea against which every warm note—flesh, red skirt, red hair rosettes, red necklace, and tamborine—glows. The jacket’s blacks are not emptily dark; they are enlivened with olive, sap, and gold strokes that keep the surface breathing. The turquoise epaulette on the shoulder does precise work: it repeats the cool of the background yet detaches itself through a sharper chroma, preventing the upper half from collapsing into a black mass. The skirt’s red is generous and slightly variegated; its scale anchors the figure to the lower edge like a bass note. Because Matisse limits the palette to a few families—blue, black-gold, red, pale flesh, and turquoise—each relation is readable, and the painting’s climate is unmistakable.

Contour as Conductor

The entire design is carried by bold brush-drawn contour. A single, unbroken line wraps the cheek and jaw, thickens at the chin, and thins as it ascends the nose. Dark bands articulate the eyelids and brows with the precision of calligraphy. The jacket’s edge is a firm ribbon of black that tacks across the chest, loops around the epaulette, and drops to the waist where it meets the red. These lines do not hedge or decorate; they declare decisions. Because the contour is so authoritative, interior modeling can remain sparse: a few olive notes under the cheekbone, a blunt shadow under the lower lip, a pale wedge on the forehead. The look of inevitability is born from this economy.

The Face: Planes, Reserve, and Presence

Matisse resists the lure of theatrical expression and instead sets the face as a system of planes that imply mood. A pale, cool highlight sits on one cheek; a greenish shadow meets it on the other, echoing the turquoise of the shoulder and tightening the color chord. The mouth is a single shape set with the slightest downturn; the eyes are almond leaves whose pupils are set a hair off-center, generating a lively, unsentimental presence. The hair is handled as two contiguous black masses that carve the oval and stabilize the head like dark wings. The expression—calm, alert, self-possessed—keeps the painting human amid its decorative vigor.

Gesture, Costume, and the Drama of the Tamborine

The tamborine introduces a circle into a world of diagonals and triangles. Its saturated red rhymes with the skirt and hair rosettes but sits in the hand as a separate form, a portable sun. The lifted arm describes an arc that begins at the shoulder seam, crosses the tamborine, and returns to the face. That circuit guides the eye and confers purpose; this is not a prop for folklore but a pictorial device that organizes the field. The costume participates as structure rather than ornament. Gold edging provides crisp borders; the embroidered bodice punctuates the dark jacket with small floral bursts; lace at the sleeve ends adds a quiet cadence at the periphery. Even the small necklace—simple red beads—reinforces the vertical axis of throat and chest and echoes the other reds without noise.

Background as Active Field

The background refuses scenery. Instead, Matisse lays a continuous field of periwinkle blue built from broad, directional strokes. Small temperature shifts—cooler at one cut edge, warmer near another—keep the plane alive. This field does two things: it brings the figure forward with striking clarity, and it unifies the composition by eliminating the distractions of illusionistic depth. The result is a shallow stage—a painterly wall—on which the figure reads like a living relief. That decorative flatness is essential to the portrait’s authority.

Light Without Chiaroscuro

Luminosity arises from adjacency, not theatrical shadow. Flesh appears bright because it sits beside the jacket’s black; the tamborine glows because red meets blue without mediating grays; gold trim shines because a narrow band of ochre borders a dark mass. The few modeled passages—on the face, at the palm, along the folds of the skirt—are constructed from clear steps of color rather than blended gradations. This approach keeps the surface clear and honest while preserving the sensation of daylight hitting costumed forms.

Brushwork and the Evidence of Process

Up close, the surface testifies to a painter working quickly yet reflectively. In the blue ground, the brush drags and sweeps, leaving bristle marks that catch light and stop the plane from going dead. In the jacket, thick strokes arrive like calligraphic notes, sometimes overshooting their path and being corrected with a counter-stroke that remains visible as a small halo. The skirt reads as a series of vertical pulls, heavier at the seams, lighter at the highlights. These traces give the painting time. One senses eyes moving, revising, and finally resting when the intervals lock.

Spain Imagined, Not Illustrated

The woman’s costume, tamborine, and stance summon Spain—perhaps Seville, flamenco, and street festival—yet the painting refuses anecdotal specifics. Matisse is not producing an ethnographic image but using “Spanishness” as a set of rhythmic cues: circular instrument, high-contrast costume, flowers at the ear, the proud hand-set of dancers. The strategy resembles his treatment of North African subjects in the same years. Motif is a pathway to structure, not a target for picturesque detail. The portrait honors cultural allure while keeping its true allegiance to pictorial order.

Comparisons with Sister Works

Seen beside “Algerian Woman” (1909), this painting shares the shallow stage, strong contour, and dominance of a few saturated reds and blues, yet the present figure asserts more kinetic poise. In relation to “Harmony in Red” and “Still Life with Blue Tablecloth,” it shares the principle of a continuous background field that fuses wall and air into a single color climate. The assertive hand on hip and lifted arm anticipate the commanding gestures of later Nice-period odalisques, while the clear silhouette and three-color architecture look forward to the large decorative panels “Dance” and “Music,” where bodies become archetypes against open grounds.

The Psychology of Poise

Gesture makes character. The hand on the hip announces readiness, the lifted arm suggests performance, and the direct yet unpressured gaze reads as mastery rather than exhibition. The figure owns the space; nothing in the blue ground presses back. That psychological poise is amplified by the costume’s engineering: a corseted bodice, structured jacket, and firm sash all present a vertical core that lets limbs move as counter-rhythms. Matisse renders not flirtation but authority—the modern woman as performer and person at once.

Ornament as Structure, Not Accessory

Calling this painting “decorative” is descriptive, not dismissive. Decoration in Matisse means that interest is evenly distributed and that pattern serves to bind parts into a whole. Gold edging clarifies edges; embroidered motifs add life at the dark center; the beaded necklace connects face to torso; the tamborine’s red repeats in skirt and hair, knitting far-apart zones into a single chord. Nothing is added for prettiness; everything does structural work.

Material Scale and Human Intimacy

The portrait’s mid-scale supports a conversational intimacy. At this size, the brush can speak plainly, cloth can be suggested with a few strokes, and the viewer can read expression without squinting. Paint is used sparingly; there is no thick impasto for its own sake. This economy of means—few colors, confident line, disciplined surfaces—functions like good conversation: clear, alive, and respectful of the listener’s intelligence.

Light, Skin, and the Green Note

One of Matisse’s subtlest devices is the greenish tint in the facial shadows. That cool note binds the face to the turquoise epaulette and the blue field, preventing the flesh from popping out as a separate, overly warm object. It also creates a delicate masklike effect that heightens the theatrical aspect of the subject without tipping into caricature. The face thus becomes the painting’s mediating instrument, balancing warm and cool, performance and person.

Why the Painting Still Feels New

More than a century later, “Spanish Woman with a Tamborine” remains fresh because it trusts essentials. A few colors—blue, red, black-gold, pale flesh, turquoise—are arranged with exactitude; lines are placed without apology; the background refuses false depth; hands and face speak through posture rather than fussed detail. The result is an image that reads in an instant and deepens with time, offering lessons for painters and designers: reduce your means, heighten your relations, let pattern carry truth.

Conclusion

“Spanish Woman with a Tamborine” is a compact manifesto of Matisse’s 1909 clarity. A single figure, a continuous blue field, and a handful of strong hues suffice to deliver presence, poise, and rhythm. Contour conducts, color structures, and brushwork keeps the surface alive. The Spanish motif lends the painting a pulse of performance, but the true subject is the choreography of planes and lines that turns costume and gesture into lasting form. Matisse shows how dignity and delight can arise from the fewest necessary means, and how a woman standing with a tamborine can become an emblem of modern pictorial grace.