Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

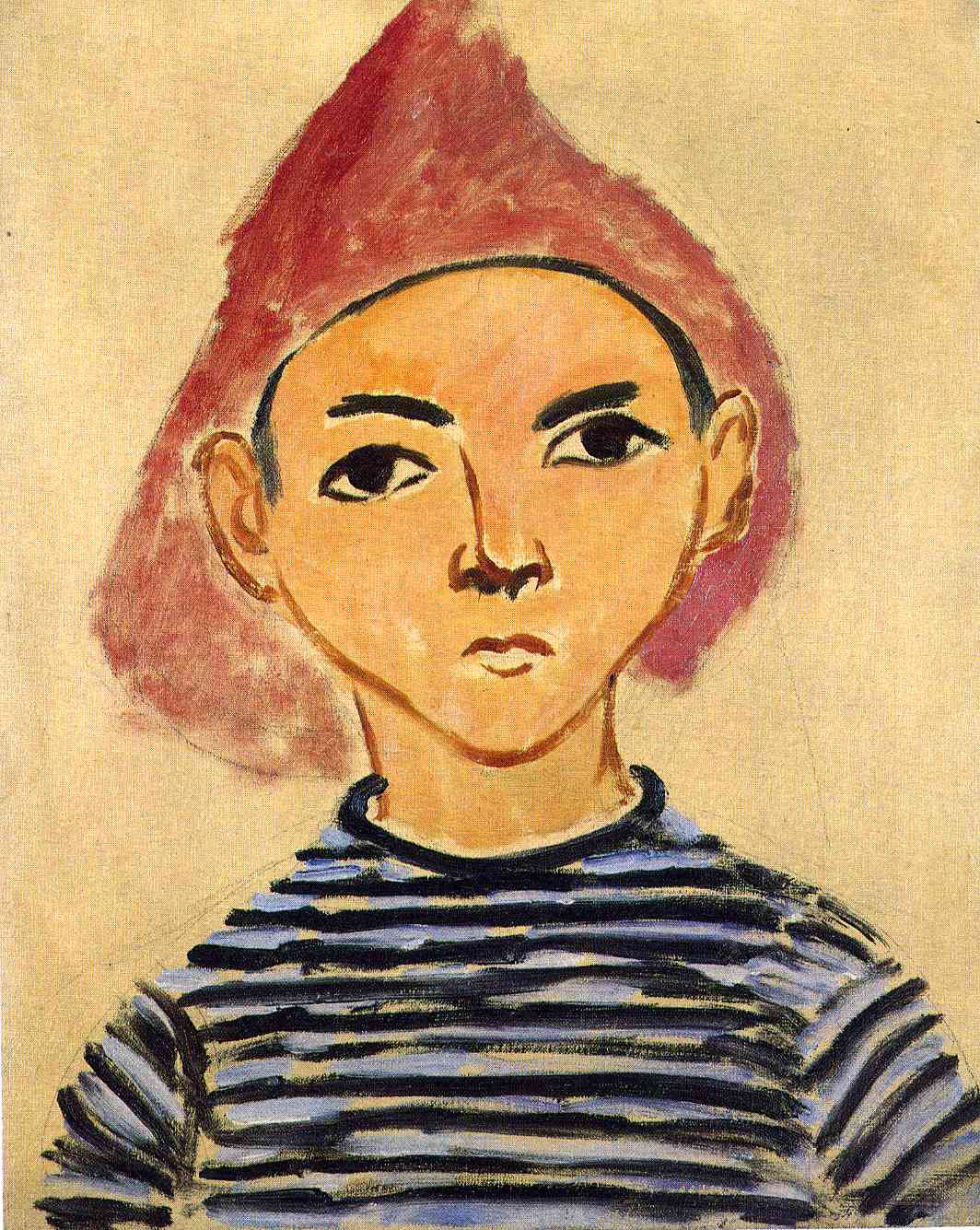

Henri Matisse’s “Portrait of Pierre Matisse” (1909) is a deceptively simple image that turns a child’s face, a striped sailor’s shirt, and a conical red hat into a manifesto of clarity. The artist’s son looks out with a direct, questioning gaze; the background is the bare weave of canvas; and the entire likeness is built from a handful of emphatic lines and a restrained, high-key palette. What first appears as a quick, affectionate sketch reveals itself, on sustained viewing, as a carefully orchestrated portrait in which contour, color, and empty space collaborate to produce presence. It is intimate without sentimentality, modern without mannerism, and perfectly of the moment in 1909 when Matisse was consolidating the explosive discoveries of Fauvism into a language of balanced, architectural color.

Historical Moment and Family Context

In 1909 Matisse had moved past the raw shock of his 1905 Fauvist canvases toward a calmer, more structural order. He wanted paintings that would read instantly at a distance and continue to reward up close; he wanted color to carry structure; he wanted drawing to be done with the brush, not a burden of academic modeling. A portrait of his son offered the ideal ground for this experiment. Pierre Matisse was an adolescent—serious, bright, and already cosmopolitan—who would later become a pivotal art dealer in New York. In the picture he is not presented as a future impresario but as a child caught in the transitional gravity between boyhood and adulthood. The father’s affection is evident, yet the painting resists the syrup of parental pride. It is a portrait of character arriving.

Composition: An Icon Made from Essentials

The composition is almost shockingly direct: a head and shoulders, full front, against a light raw ground. The triangle of the red hat crowns the vertical of head and neck; the horizontal cadence of the striped shirt sets a counter-rhythm. Because the background remains unpainted, figure and ground lock with unusual clarity. The absence of props, scenery, and cast shadows purifies the rectangle. Everything that remains—the triangular hat, oval head, almond eyes, small mouth, and striped torso—contributes to a signal as legible as a poster.

Color Strategy: A Chord of Flesh, Red, and Indigo

Matisse narrows the palette to a few interlocking notes: soft apricot for flesh, a coral-crimson for the hat, deep indigo and midnight blacks for the shirt’s stripes, and the warm straw color of the untouched canvas. The flesh is not blended through a gamut of browns; instead, warmer and cooler pinks sit beside each other to turn cheek and temple. The hat’s red is brushed thinly at the edges, allowing the canvas to kindle through and creating an airy halo that lightens the whole zone. The dark stripes of the jersey are laid with loaded, confident strokes that carry hints of blue, so the garment breathes rather than sits as an opaque slab. The restricted palette has a double effect: it fixes attention on the face while establishing a modern, almost graphic harmony across the surface.

Contour as Structure and Expression

A single line, drawn with the brush and saturated pigment, gives the portrait its skeleton. It arcs around the skullcap hairline, carves the ear, descends the jaw, and locks the chin into the small wedge of neck. The same line thickens to secure the eyebrows, which angle inward with a seriousness that keeps the image from cuteness, and thins around the nostrils and eyelids to maintain delicacy. There is no timid correction; when Matisse moves, he moves decisively. At a few junctures the contour hesitates and reasserts itself a few millimeters away, leaving a pale interval that records revision. Those slight pentimenti make the portrait feel alive, the result of looking and adjusting rather than the execution of a diagram.

Eyes, Mouth, and the Question of Likeness

The eyes are the most elaborated features, shaped as almond leaves set with black pupils that are not perfectly symmetrical. That asymmetry contributes to the child’s alert, unposed regard. The mouth is small, pinched, and slightly off-center; the top lip is a single stroke, the lower lip a short bar of ochre and rose. Rather than build likeness with a catalogue of details—eyelashes, pores, subtle dental anatomy—Matisse captures it with proportion and interval: the distance between brow and eye, the tilt of the ears, the breadth of the forehead, and the gap of air under the lower lip. Because those relationships ring true, the portrait convinces without descriptive fuss.

The Red Hat: Triangle, Halo, and Tone Setter

The hat’s triangular mass does more than crown the head; it sets the emotional key. Its ragged edges and variable density prevent it from reading as a rigid cone. Instead, the red spreads outward like a soft aura, warming the raw canvas and giving the figure a mild, iconic glow. The triangle also organizes the geometry: it counterbalances the horizontal stripes below and presses the gaze back down into the facial oval. Many viewers have associated the form with a Phrygian cap—the cap of liberty in French iconography. Whether or not Matisse intended that specific reference, the association suits the portrait’s mixture of youthful individuality and republican simplicity.

The Striped Sailor’s Shirt: Rhythm and Grounding

The marinière—the classic French sailor’s jersey—anchors the portrait with rhythm. Matisse paints the stripes as energized bands, not ruler-straight lines. They thicken and taper, echoing breath and the underlying torsion of shoulders. The indigo strokes leave small reserves of canvas between them so that the shirt’s white glows rather than chalks. The garment’s casual modernity counters any whiff of costume in the hat and locates the child in contemporary life rather than historical pageant. At a structural level, the horizontal bars keep the lower half of the composition visually heavy, preventing the triangular red hat from tipping the rectangle upward.

Background as Active Silence

There is as much meaning in what Matisse leaves unpainted as in what he paints. The unprimed, uncolored ground gives the picture air and historical depth: we see the weave of the cloth, the tooth that catches stray hairs of pigment, the small warm shifts where oil meets linen. This active silence allows the portrait to glow from within. It also keeps the work from collapsing into an illustrative vignette. The child is not “in” a room; he is in the painting, which behaves like an object with its own material presence rather than a window into a story.

Modeling Through Planes Rather Than Shadow

Where a 19th-century academic portrait would elaborate a hierarchy of shadows to turn form, Matisse uses planar shifts of temperature. On the forehead a warmer apricot modulates to a cooler, gray-pink near the temple; at the nose, a single wedge of deeper tone sets the bridge and tip; at the jaw, the flesh cools where it approaches the darker hairline. The neck, crucial for anchoring the head, is a simple column of peach that darkens slightly beneath the chin. Because transitions are minimal and edges remain crisp, the form reads with clarity even at distance—a principle Matisse pursued in all his 1909 work.

Brushwork, Speed, and Evidence of the Hand

The painting’s vitality comes from the variety of its touch. The hat is swept with quick, slightly dry strokes that let the linen breathe; the shirt’s stripes are rolled from the wrist with a thicker, wetter load that leaves a glossy ridge; the facial features are set with shorter, more deliberate marks. These differences produce a readable hierarchy: hat for tone, shirt for rhythm, face for character. Matisse refuses to sand those differences into an anonymous polish. He wants the viewer to sense the tempo of making—the quick crown, the steady shirt, the careful eyes—because that tempo itself is part of the portrait’s truth.

The Psychology of Reserve

Children’s portraits often overstate innocence or mischief. Here the mood is one of intelligent reserve. The brows gather slightly; the lips refuse a smile; the gaze is attentive but not ingratiating. This restraint reads as respect. The father avoids projecting an adult narrative onto the child and instead honors the child’s gathering selfhood. The red hat and striped shirt make the image lively; the expression keeps it from becoming a costume piece. The tension between graphic simplicity and psychological poise is the portrait’s quiet drama.

Dialogue with Matisse’s Larger Project

Set beside earlier experiments such as “Woman with a Hat” or “The Green Stripe,” the portrait reveals both continuity and change. The bold contour and high-key color recall the Fauvist shock, but the orchestration is calmer. It aligns with the principles that culminate a year later in the great panels “Dance” and “Music,” where large planes, clear edges, and simplified bodies must hold across architectural spaces. The portrait can be read as a domestic version of that ambition: can the fewest possible means deliver complete presence on a small scale? “Portrait of Pierre Matisse” answers decisively in the affirmative.

The Role of Memory and Intimacy

A family portrait always doubles as a record and an emblem. This image remembers a particular child in a particular season—lean face, watchful eyes, the haircut of the time, the striped shirt probably worn often. Yet it also abstracts the child into a durable sign: a triangle for the cap, an oval for the head, bars for the shirt. That oscillation between the specific and the general lets the painting remain intimate without narrowing into private sentiment. Viewers can enter because the portrait opens onto archetype while retaining the grain of a life.

Material Economy and Ethical Clarity

There is an ethics in Matisse’s economy. He gives the viewer exactly what is needed to believe and nothing more. No labor is expended to simulate fabrics or light effects for their own sake; every mark does structural or expressive work. The portrait’s honesty about its making—wet over dry, reserves of canvas, visible corrections—embodies a broader modern creed: truth to materials, clarity of intention, and respect for the viewer’s intelligence. That ethical clarity is part of why the image continues to feel fresh.

Influence and Afterlife

Beyond its place in Matisse’s oeuvre, the portrait prefigures the graphic clarity of mid-century poster design and the simplified, high-contrast portraits of later painters. It shows how a face can be carried by contour and limited color without collapsing into caricature. Pierre’s later career as an art dealer—in which he championed European modernists in America—gives the painting an incidental historical resonance. The boy who here looks outward with measured curiosity would help shape the reception of the very modernism that formed his father’s art.

Close Looking: Small Decisions That Carry Weight

The picture rewards attention to micro-choices. The left ear is more detailed than the right, nudging the head’s turn. The tiny light along the upper lip animates the mouth. The hat’s red is dragged thinner at the uppermost tip, letting the canvas sparkle and keeping the triangle from feeling heavy. A cool, smoky stroke borders the right cheek, separating flesh from background without hardening the edge. These small, almost invisible decisions accumulate into the sensation of inevitability—nothing seems added, nothing missing.

Why the Portrait Endures

“Portrait of Pierre Matisse” endures because it trusts essentials. It believes that the distances between features, the pressure of a line, the relation of a few colors, and the dignity of empty space suffice to summon a person. In an age that often asks images to furnish endless information, the portrait demonstrates a different path: precision through omission, presence through rhythm, intimacy through clarity. It is a father’s view, an artist’s experiment, and a luminous fragment of 1909—still legible, still generous, still new.

Conclusion

Matisse’s painting of his son distills portraiture to a lucid grammar. The triangular red hat, the measured oval of the head, the resolute gaze, the breathing stripes of the shirt, and the quiet field of raw canvas produce a likeness that is both affectionate and exact. Color establishes climate, contour carries structure, brushwork keeps the surface alive. Everything unnecessary falls away. What remains is a modern icon of attention—a child held in the light of a painter’s eye, rendered with the fewest strokes required to make him fully present.