Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

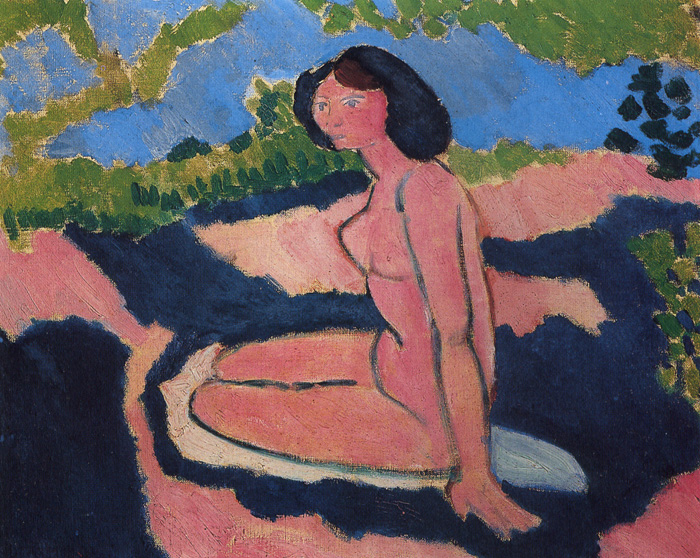

Henri Matisse’s “Pink Nude” (1909) is a distilled meditation on the body, light, and landscape, where heightened color replaces description and contour becomes the primary architecture. A young woman sits in profile on a pale oval, her torso turning just enough to send a frank glance over her shoulder. The fields around her are not a literal shore so much as a theater of color: bands of mossy greens, chalky pinks, and pools of dark blue that cut through the scene like shadowed water. With a handful of decisive means—large planes, assertive outlines, and measured intervals—Matisse builds a nude that is at once sensual and serene, modern yet timeless.

Historical Context and Matisse’s 1909 Turn

By 1909 Matisse had moved beyond the explosive clashes of early Fauvism toward a calmer, more architectonic language. Color remained intense, but it now served structure rather than spectacle. “Pink Nude” belongs to this period of consolidation, in dialogue with bathers and Arcadian scenes he was preparing as he developed the great panels “Dance” and “Music.” In those years he aimed to extract maximum presence from minimal means: reduce the palette, simplify the pose, anchor the figure in a shallow stage, and let the painting’s truth emerge from relations of hue and line. The nudity here is not academic display; it is a classical subject reimagined as an arrangement of rhythms and planes.

Composition and the Geometry of Calm

The composition is built on a triangular armature. The nude’s seated posture forms the triangle’s base along the lower margin, while the erect torso rises as the central axis before bending gently toward the picture’s right edge. Around her, the landscape locks into stacked bands that both frame and stabilize the figure: a dark blue ribbon that reads as stream or shadow, a pink embankment, and a greener belt of vegetation near the horizon. These belts, offset and staggered, keep the image dynamic without crowding the sitter. A pale oval beneath the figure—rock, towel, or stylized ground—gives a deliberate pedestal that prevents the body from dissolving into the surrounding blues. The overall geometry creates calm tension: anchored below, open above, the figure poised between repose and alertness.

The Architecture of Color

Color is the work’s structural engine. The body’s pink—vivid yet slightly cooled—is tuned to sit between the warmth of the foreground pinks and the coolness of the surrounding blues. The landscape’s green fringe is not botanical description; it is a temperature counterweight that keeps the scene from tipping into a two-color duel. Matisse’s palette compresses to a succinct harmony: pink for flesh and ground, deep blue for water or shadow, green for vegetation, and a tracer of pale gray-white to lift the seat and edges. Because each field is cleanly placed, the eye reads the scene immediately from a distance, then discovers subtler modulations up close—warm rose along the breastbone, cooler lilac at the hip, olive whispers within the green.

Contour as Conductor

Bold, elastic contour lines—dark, sometimes tinged with blue-green—conduct the figure’s rhythm. One sinuous stroke defines the outer curve from shoulder to knee; the same line tightens briefly at the waist, then loosens across the thigh to keep the form breathing. A second contour runs along the far edge of the torso, clarifying the twist that turns the chest toward us. These outlines do not imprison the color; they steer it, the way a lead came holds stained glass. Where Matisse needs emphasis—the junction of pelvis and thigh, the angle of the breast—the line presses harder; where he wants air—the cheek, the forearm—it thins or even breaks, letting the surrounding field participate. With a few arcs, he converts anatomy into architecture.

Modeling by Planes, Not Shadows

The body is not built with graduated chiaroscuro. Instead, Matisse models with juxtaposed planes: a warmer pink abuts a cooler one at the rib, a thin lilac sliver turns the calf, a whitish highlight sits on the kneecap like a precise accent. The viewer completes the three-dimensional feel because the intervals are right. This strategy keeps the painting legible in bright light and at scale, a requirement that ties the picture to the decorative ambitions of the period. It also preserves the surface’s honesty; nothing denies that we are looking at color laid upon canvas.

Brushwork and the Living Surface

Up close, the surface is animated by varied touch. In the dark blue pools the brush drags and swirls, leaving slight ridges that catch light and deepen the sense of density. The pink grounds are dragged more thinly, allowing warmer underlayers to flicker through and give the field a sunlit vibration. On the nude, paint is creamier, especially at shoulder and knee, where small, deliberate dabs define form without fussy blending. The green crown of foliage is laid with clipped strokes and uneven edges—more suggestion than transcription—so that the entire upper register feels wind-stirred. These differences in facture prevent any single zone from going inert; the image breathes.

Light as Relationship

There is no theatrical source of illumination. Light arises from adjacency and temperature. The body seems to glow because warm pink presses against the near-black blues; the seat’s pale oval reads bright because it sits within a surround of darkness; the upper horizon feels airy because green brushes up against blue. A few placed highlights—along the nose, on the thigh, where the forearm turns—are enough to trigger the mind’s sense of shine. Matisse’s light is built, not mimicked; it is a consequence of the painting’s structure rather than an independent effect.

Space and the Shallow Stage

Depth is shallow yet convincing. The dark shapes cut across the lower half like water or shadowed ground, then recede under the pink bank and green rim. The figure sits firmly in the foreground because the strongest contrasts of value and temperature cluster around her. Overlap—a hand in front of thigh, torso before the blue—finishes the spatial cueing. This controlled shallowness keeps the viewer close to the subject, turning the picture from a window into a patterned stage where color and line can play their roles without the distraction of deep perspective.

The Pose: Poise, Modesty, and Presence

The sitter’s pose is both modest and declarative. Knees folded under, torso upright, head turning back: it is a classical contrapposto translated into seated terms. The twist of the torso reveals the breast yet keeps the figure self-contained, neither coy nor defiant. The eyes are direct, the mouth quiet. The pose suggests a moment of pause rather than performance—a person resting after bathing or simply at ease in open air. Because facial features are simplified, expression emerges from posture, and the painting achieves a reserve that respects the sitter’s dignity.

Landscape as Ornament and Echo

The surrounding fields behave less like topography and more like a textile pattern that echoes the figure’s rhythms. Jagged green strokes repeat the hair’s dark mass at a distance; the blue pools mirror the body’s curves, creating negative shapes that rhyme with thigh and forearm. The pink embankment that cuts behind the shoulders makes a gentle halo, a chromatic cushion that protects the head against the darker blues. Ornament here is not an addition; it is how space holds the body—through repetition, echo, and measured contrast.

Dialogue with Sister Works

“Pink Nude” converses with several canvases from 1909. Its limited palette and shallow banded space link it to the coastal bathers and to “Naked by the Sea,” while its emphasis on clean contour anticipates the monumental clarity of “Dance.” Compared with the earlier “Blue Nude” (1907), this work is calmer, less sculptural in thrust, and more about equilibrium than shock. It also prefigures the Nice-period odalisques, where textile logic absorbs figures into patterns; the difference here is the outdoors, which keeps the climate brisk and the palette spare.

The Ethics of Simplification

Simplification in “Pink Nude” is not a denial of complexity but a method for telling truth with economy. By eliminating accessory detail—no ripples, no pebbles, no ornamented props—Matisse concentrates on the few relations that make the image cohere: warm flesh against cool shadow, firm contour against soft field, a poised vertical rising out of a braided ground. The result is clarity that reads as respect: attention is given to structure and poise rather than to spectacle.

Material Evidence and the Trace of Process

Subtle pentimenti remain visible: a shifted contour near the waist, a dark edge beneath the knee where the blue was adjusted, small halos where pink meets green. These traces of revision give the work time and credibility. You can sense the painter nudging intervals until the figure sat exactly within the banded landscape. The final balance feels inevitable precisely because the canvas shows how it was achieved.

Psychological Temperature and the Mood of the Painting

The mood is lucid and unagitated. Cool blues hold the heat of pinks in check; the greens at the horizon lend a breeze; the sitter’s outward gaze keeps the space social without inviting intrusion. The painting models the serenity Matisse sought in this period: an art that restores attention rather than scattering it, that invites the viewer to stay and breathe with the image. The nude is not isolated from her environment; she is tuned to it, the way a single instrument is tuned to a key.

Why the Painting Endures

“Pink Nude” remains fresh because it resolves several enduring problems with disarming simplicity: how to render a body without descriptive fuss, how to place a figure in landscape without dissolving either, how to make color carry both form and feeling. Its lessons travel beyond painting. Designers borrow its triadic harmony; photographers learn from its shallow stage and strong silhouette; choreographers find rhythm in its curves and counter-curves. The work endures not because it summarizes history but because it demonstrates decisions—what to keep, what to omit—that continue to feel right.

Conclusion

Matisse’s “Pink Nude” is a compact statement of his 1909 clarity. A seated figure, a few belts of landscape, a concise palette, and a small set of authoritative lines are enough to generate presence. The nude glows without exhibitionism, the space supports without distracting, and every inch of the surface participates in a quiet rhythm of echoes and rests. In reducing the world to essentials, Matisse does not impoverish it; he reveals how little is needed for an image to feel complete, humane, and radiant.