Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

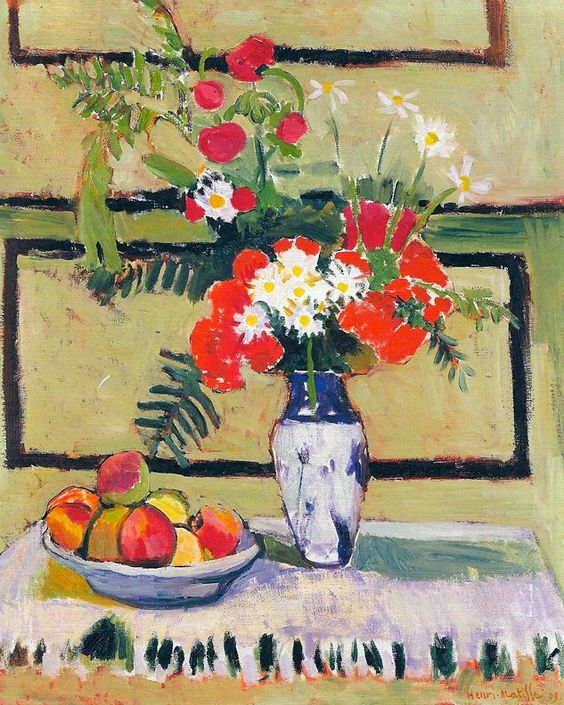

Henri Matisse’s “Flowers and Fruit” (1909) stages a luminous conversation between two classic still-life motifs—a vase of blossoms and a bowl of ripe fruit—set against a pale, patterned interior that feels as much like a textile as a room. Nothing in the canvas aims for trompe-l’œil illusion. Instead, Matisse organizes the scene through large, legible color planes, decisive contours, and a rhythm of repeated circles and ellipses, so that flowers, fruit, table, and wall become parts of one decorative order. The effect is at once intimate and architectural: a tabletop vignette that reads like a complete world.

A Moment of Consolidation After Fauvism

By 1909 Matisse had moved from the shock tactics of early Fauvism to a calmer, more structural language. The chroma remained bold, but color now carried the architecture of the picture rather than exploding it. “Flowers and Fruit” embodies this turn. The palette is high—scarlet blossoms, lemon-green wall, fresh leaves, peach and yellow fruit—but everything is tuned to a stable chord. Contour lines, often a dense blue-black, act like the lead cames in stained glass, containing and energizing the color without letting it run wild. The painting rejects anecdote and virtuoso modeling in favor of an economy that places weight on relationships: red against green, round against round, vertical vase against horizontal bowl.

Composition and the Architecture of the Table

Matisse constructs the composition on a clear scaffold. The vase stands just right of center, a vertical mast that steadies the image. At left, the shallow bowl of peaches and apples provides a counterweight, its low ellipse and stacked rounds echoing the floral disks across the vertical axis. The table runs parallel to the picture plane, capped by a cloth whose fringed lower edge becomes a decorative border. Behind, the wall is treated as a field divided by rectangular moldings outlined in dark strokes. These rectangles repeat the picture’s own frame, pulling the interior and the canvas into visual rhyme. Nothing recedes steeply; depth is built by overlap and placement rather than by perspective. The result is a shallow, convincing stage on which pattern can sing.

Color Architecture and the Logic of Complements

Color does the heavy lifting. The background’s citron-olive wall sets a mellow, sun-warmed climate. Within that climate, Matisse launches complementary fireworks: the saturated reds of poppies or zinnias flash against the green foliage; the pure whites of daisies cool the bouquet and keep the reds from overwhelming; the blue accents on the porcelain vase and along certain contours intensify surrounding oranges and yellows. In the fruit, pinks and golds hover between warm and cool, their blushes recorded with swift, opaque touches. The tablecloth is a pale, cooling lavender-white that gathers the entire harmony and reflects small echoes of each hue. Because the palette is carefully measured, even the most intense notes feel inevitable rather than strident.

The Decorative Background and the Refusal of Empty Space

The wall behind the still life is not a neutral void. Matisse articulates the paneling with dark frames that punctuate the field and slow the eye. These geometric bands converse with the vertical of the vase and the low oval of the bowl, stabilizing the more improvisatory rhythms of leaves and blossoms. He treats the wall as a painted textile, letting small swipes of warm undercolor flicker through the greenish ground. That shimmer prevents the background from going dead and integrates it with the more actively brushed objects in front. Space is simplified without becoming blank; pattern holds the scene together.

Drawing With the Brush

Matisse draws directly in paint. The stems are swift, elastic lines that arc into place. Leaves are blocked with a single loaded stroke, then corrected by a darker contour or a lighter scumble at the edge. The fruit’s roundness arises from a half-circle of darker paint nested within a lighter crescent; a highlight is a single knife-clean dash. On the vase, cobalt marks and ink-like squiggles suggest both pattern and shadow, doing double duty without fussy description. The bowl’s ellipse is poised and unsentimental: one firm curve laid once, corrected only where necessary to catch the weight of the fruit.

Rhythm, Repetition, and the Music of Rounds

Repetition is the painting’s quiet engine. Circles and near-circles recur—daisy heads, red blooms, apples, peaches, the bowl’s rim, the vase’s mouth—creating a visual music of beats and rests. Fern fronds and long leaves introduce syncopation, their serrations and diagonals breaking the roundness so the eye doesn’t doze. The fringe at the cloth’s edge adds a final staccato line of dark verticals, a delicate counter-rhythm that keeps the lower boundary lively. Because these motifs recur across the whole surface, attention can move anywhere without falling into unimportant zones.

Light Without Chiaroscuro

There is no single light source casting hard shadows. Instead, light is a function of adjacency. White petals dazzle because they are ringed by greens and reds; the fruit glows because warm lights sit beside cool half-tones; the vase appears luminous because its blues press against a pale body that shares the tablecloth’s cool. Matisse’s highlights are not blended; they are placed. A stroke of creamy paint at the rim of the bowl, a bright daub on a peach, a small halo around a leaf—these are enough to create the sensation of brilliance without sacrificing the flat integrity of the surface.

The Vase as Mediator

The porcelain vase is more than a container. Its cool whites and patterned blues mediate between the hot blossom mass and the cool tablecloth, between the warm wall and the green foliage. Matisse mottles its body with pale lilac and blue stains that echo the table’s color and anticipate the dark accents around the paneling. The narrow neck funnels the bouquet upward, keeping the stems gathered so the flower heads can burst outward with clarity rather than confusion. The vase is the composition’s hinge; remove it, and the picture loses its axis.

The Bowl of Fruit as Counterweight

The fruit dish supplies gravitas. Low to the table and heavy with peaches and apples, it counters the airy lift of the flowers. Matisse paints each fruit as a simple, tactile volume—two or three color notes at most—arranged so their rounds nestle and push against the bowl’s lip. The fruit’s color scale, skewing toward orange, yellow, and rosy red, complements the bouquet while avoiding literal match. That slight difference in temperature and saturation keeps the two halves of the still life from collapsing into a single red mass. The bowl’s shadow—cooler and darker at its core—anchors it firmly to the cloth.

Tablecloth, Edge, and the Meaning of Borders

The white cloth is a quiet marvel. Laid across the table and dropping just enough to show a fringe, it introduces a soft field where small color reflections gather: whispering lilacs from the vase, pale greens from the wall, and the faintest echo of fruit tones. Along the lower edge, the black-green tassels read both as textile detail and as a drawn underline that finishes the composition. Matisse uses borders like a composer uses cadences: to signal resolution while leaving the harmony ringing.

Surface, Facture, and the Presence of the Hand

The surface is animated by a range of touches. In the wall, thin layers leave the tooth of the canvas alive, so the ground breathes. In the flowers, thicker, buttery strokes sit on top, catching light with their micro-relief. Leaves are dragged wet into wet, producing a bruised edge where green meets red. The tablecloth’s scumbles allow earlier layers to peek through. These material facts are not incidental; they are how the painting communicates time and attention. You can follow the decisions—where Matisse corrected the height of the bouquet, widened a bowl, or pushed the panel lines to better balance the mass of red blooms.

Space and the Shallow Stage

Depth is created by overlapping bands and a few carefully staged shadows. The bouquet sits clearly in front of the wall because its contours bite into the paneling; the bowl sits on the table because a cool shadow pools beneath it and because its ellipse aligns with the table’s edge. Beyond that, the room does not open into recession. This shallow stage keeps the eye at the surface where color relationships are the true subject. The still life is not a view through a window but a woven tapestry of shapes and tones.

Tradition and Matisse’s Inheritance

“Flowers and Fruit” acknowledges a long lineage of French still life—from Chardin’s quiet masterpieces to Cézanne’s rigorous apples—while proposing a new ethics of clarity. Like his predecessors, Matisse respects the tabletop as a theater of ordinary abundance. Unlike them, he refuses painstaking modeling and perspective devices, choosing instead a decorative order that is honest about the canvas. The painting shows how modernity can honor tradition without mimicry: keep the objects, keep the tabletop, but build the picture from color and contour so that it breathes like a textile and sings like a score.

Ornament as Structure, Not Accessory

For Matisse, “decorative” names a method, not a category. Ornament is what happens when intervals are exact, when repetition and variation distribute interest evenly, when the eye can roam without falling into dead zones. In “Flowers and Fruit,” ornament arises from the play between geometric paneling and organic forms; from the alternation of circles and fronds; from the exchange of cool and warm within a stable climate. Far from being applied prettiness, this order is the very structure that lets the still life feel inevitable.

Psychological Temperature and Domestic Utopia

The picture’s mood is bright but not noisy, serene but not bland. There is no drama beyond the seasonal one suggested by daisies and ripe fruit. The interior feels hospitable and sunlit, a modest domestic utopia where objects are chosen for their intervals as much as for their use. Matisse’s oft-stated desire for an art that offers balance and repose is realized here without sentimentality. Calm is earned through discipline—of palette, of contour, of placement.

Why the Painting Still Feels Fresh

More than a century later, the painting remains fresh because it trusts a few strong relationships. A citron wall warms the air; a mass of red flowers lifts; a porcelain vase cools; a bowl of fruit grounds; a white cloth collects and unifies. The eye senses that nothing is arbitrary. Each mark performs a task, and each color exists because of the colors that surround it. Viewers accustomed to photographic description discover another kind of truth: not the inventory of surfaces, but the clarity of relations.

Conclusion

“Flowers and Fruit” compresses Matisse’s 1909 ambitions into a single tabletop: color as architecture, contour as conductor, pattern as structure, and simplicity as a form of generosity. The vase and bowl converse across the center; the wall’s paneling steadies their exchange; the tablecloth’s fringe completes the cadence. Blossoms and peaches are not copied but composed, their rounds and leaves forming a rhythm that feels as natural as breathing. The painting honors ordinary things by arranging them with exact care, proving that harmony is made, not found—and that a room organized by color can offer a durable happiness.