Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

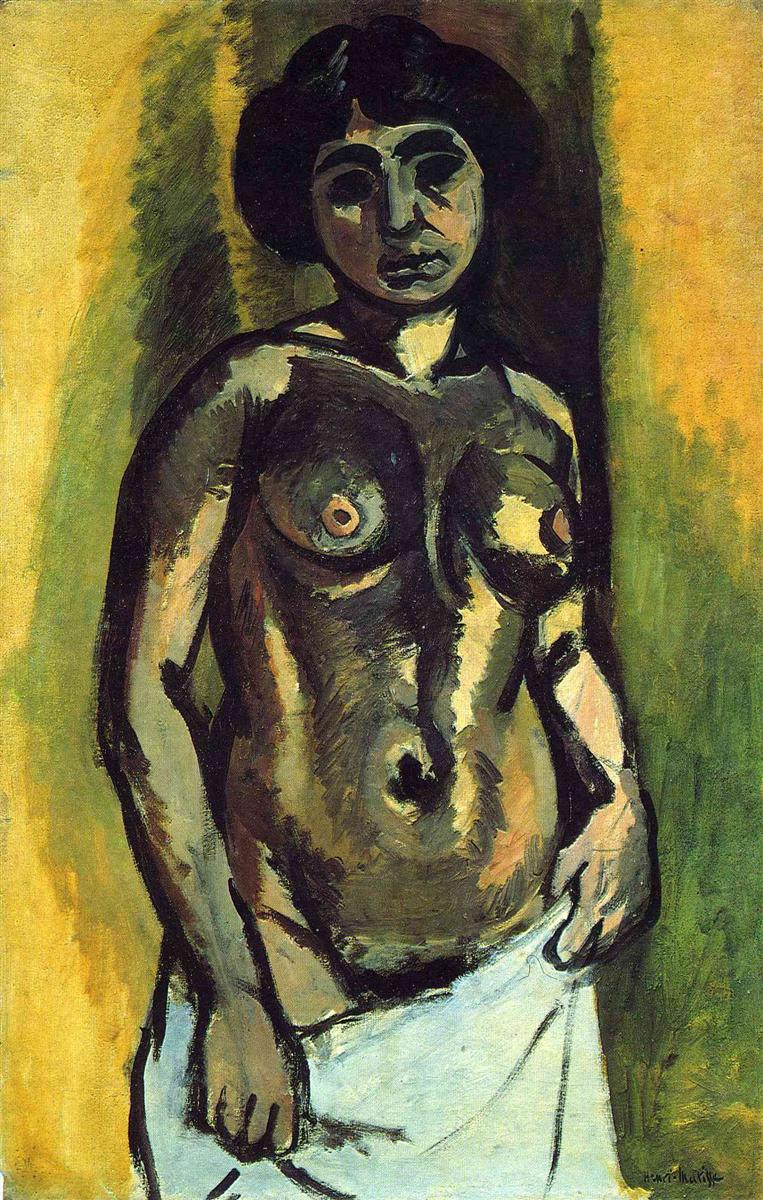

Henri Matisse’s “Nude (Black and Gold)” (1908) is a fierce, frontal study of the human body that compresses drawing, color, and sculptural weight into a single, blazing statement. The figure stands close to the picture plane, cropped at the thigh, with a white cloth knotted loosely at the hips. Her head tilts slightly downward; thick, black contours web across the torso, breaking the flesh into assertive planes. Around her, a vertical field of yellow-gold and green presses in, making the body read like a relief carved from light and shadow. The painting belongs to a critical juncture in Matisse’s practice, when the shock of Fauvist color gave way to a deeper inquiry into structure, mass, and the expressive potential of the brush. It is not a decorative nude. It is a body made of decisions—speedy, economical decisions that accumulate into a presence of startling gravity.

Historical Context and the Turn from Fauvism

By 1908 Matisse had absorbed the turbulence of his Fauve years and begun to convert chromatic boldness into a more architectonic language. The year yields both radiant interiors like “Harmony in Red” and condensed figure experiments such as this nude. In each case, color and contour do not merely describe; they organize the entire pictorial event. “Nude (Black and Gold)” occupies a charged zone within that evolution. Its palette is limited, almost austere, compared with the detonations of 1905–1906. Yet the restraint intensifies expression. Black becomes an active color, not a corrective; gold and green serve as structural planes rather than background filler. The painting tracks Matisse’s search for clarity and simplification while sustaining the raw energy that first defined his modernism.

Subject, Scale, and the Ethics of Nearness

The model stands so close to us that her body seems to lean into our space. This nearness eliminates the buffer of anecdote and setting. No carpet, no chair, no studio paraphernalia dilutes the encounter. The white cloth at the hips tells us only that the figure is nude and that modesty is a contingent, adjustable veil. Matisse neither eroticizes nor distances the sitter. He refuses the academic ideal and the coy, mythological alibi. The body bears its weight frankly: heavy hands, deep navel, strong shoulders, and breasts modeled by clotted, directional strokes. Nearness becomes an ethic—an insistence that painting can honor the body by showing how it is built on the canvas.

Composition and the Vertical Armature

The composition is a vertical column. The shoulders flare to form the capital; the torso descends in powerful, slightly twisting planes; the white cloth creates a stabilizing base. Two flanking color zones—golden on the left, green on the right—function like pilasters, containing the figure and amplifying its monumentality. The centered axis is broken just enough to keep the form alive: one shoulder higher than the other, one breast more forward, one hand slack, the other gripping the drape. These asymmetries generate the subtle rotation that prevents the nude from becoming a static icon. The cropping at the thigh heightens immediacy and invites the viewer’s imagination to complete the stance.

The Palette of Black, Gold, and Green

The title’s colors are not merely descriptive; they are the painting’s logic. Black is deployed in heavy bands and calligraphic sweeps that articulate major junctures—the sternum, the under-breast, the navel, the clavicles, the edges of arms, and the shift from belly to hip. Gold fills interstices, vibrating between flesh and field. Green steadies the right side like a cool counterweight, preventing the gold from swallowing the figure. The white cloth, a small reserve of brightness, calibrates the whole. Together these tones form a triad that reads at once as body and as abstract structure. Instead of building volume from countless halftones, Matisse toggles between a few calibrated notes, letting the eye perform the synthesis.

The Productive Violence of Line

The black contour in this picture is not an outline timidly hugging forms; it is a tool that cuts into them. Strokes rake across the torso in short slashes, then broaden to encircle a shoulder or press the cheekbone into relief. The paint alternates between oily, loaded passages and dry, scumbled marks that leave the weave of the canvas breathing through. This “productive violence” is not gratuitous. It translates the energy of looking into the energy of making. The line insists on decisions, on the refusal to blur. Even where it is almost brutal—at the edge of the arm, across the breast—it gives the body conviction. You do not see a diagram of anatomy; you feel the painter wresting image from matter.

Brushwork and the Living Surface

Matisse’s brushwork keeps the surface intensely alive. He scrapes, drags, and patches, allowing earlier layers to flash at the margins of later ones. In the gold ground, strokes fan out like feathery halos, creating a nimbus that both isolates and irradiates the figure. In the flesh, strokes declare directionality. Over the sternum they descend in narrow, vertical ticks; across the abdomen they fan diagonally, reinforcing the gentle twist of the torso. The varied pressure of the brush prevents large areas from going dead. Paint remains paint: you sense the viscosity, the split bristles, the moment when pigment runs thin and the stroke breaks into grain. This candor is central to the painting’s authority.

The Face and Mask-Like Presence

The head seems carved more than painted. Eyes, nose, and mouth are established with blunt, abbreviated planes that stop midway between description and emblem. The effect is mask-like, a quality Matisse explored in dialogue with African and Oceanic sculpture that entered Parisian collections in the early twentieth century. Here the mask is not a quotation but a method. It strips the face to its structural necessities, concentrates expression into the tilt and heaviness of the features, and resists sentimental reading. The sitter’s gaze is downward, inward, or simply withheld. That refusal to perform for the viewer grants a dignity that offsets any vulnerability implied by nudity.

Primitivism, Classicism, and the Modern Nude

“Nude (Black and Gold)” balances two currents often seen as opposites. On one hand, the black structuring lines and generalized features resonate with so-called “primitive” art, whose directness and clarity of form inspired many avant-garde artists. On the other, the work asserts a classical sense of mass and proportion. The body is not distorted for shock; it is simplified for strength. The white hip drape echoes antique statuary just as the flanking color fields frame the figure like a niche. Matisse’s modern nude rejects the idealized smoothness of academic classicism while absorbing its architectural poise.

Light Without Illusion

The painting produces the sensation of light without recourse to naturalistic modeling. There is no single, traceable light source. Instead, light is an effect born from the collision of tones—gold against black, green against brown, white against everything else. Breast and collarbone read as lit because adjacent passages darken dramatically. The belly seems to bulge because lighter strokes huddle near the navel while darker ones tighten around the flanks. This is not deception but a controlled abstraction of visual experience. Matisse declares that painting’s truth lies in relationships on the canvas, not in the mimicry of optics.

The Body Unidealized

One of the portrait’s quiet revolutions lies in its acceptance of bodily facts that academic convention smoothed away. The abdomen is soft and complex, the navel deep, the breasts asymmetric, the hands heavy and unposed. Far from diminishing beauty, these particulars create a human presence that is specific and dignified. They also offer the painter more to work with: more edges, more intervals, more opportunities for brush and contour to discover form. The nude is not a fantasy object; she is a person whose body carries time and gravity, made monumental by the seriousness of attention.

Space, Ground, and the Relief Effect

The gold and green ground plays a crucial role. Their vertical sweep suggests a shallow, curving surround, so that the figure reads almost as a relief mounted on a colored wall. The ground presses near the shoulders and flanks, activating edges and preventing the figure from floating. At the same time, stray feathery strokes from the ground wander onto the arm or shoulder, knitting figure and field without erasing their difference. The relief effect connects the painting to sculpture while preserving the flat integrity of the canvas—a hallmark of Matisse’s spatial logic throughout this period.

Kinships and Contrasts with Sister Works

Viewed beside Matisse’s “Blue Nude” of the previous year, this painting reveals a shift from expansive pose to concentrated stance, from cool chromatic audacity to limited, earthen heat. Both works share a devotion to sculptural mass and to the simplification of facial features, but “Nude (Black and Gold)” compresses the energy into a more intimate register. Compared with the sumptuous orchestration of interiors like “Harmony in Red,” the nude is almost ascetic—a laboratory of contour and tone. Together, these works map a continuum in Matisse’s 1907–1908 practice: from color-flooded environment to figure hammered out of a narrow palette.

Material Evidence and the Trace of Process

A close look shows pentimenti where contours were shifted, fingers rearticulated, or the drape redrawn. These revisions remain visible, not hidden under cosmetic overpaint. Matisse wants the viewer to feel the time of making—the trial, the correction, the moment a problem is solved in a stroke that he trusts enough to leave alone. The signature tucked near the lower right emphasizes that the painting is an artifact of the hand as much as an image of a body. Its honesty about process is central to its modernity.

Psychological Temperature and the Ethics of Looking

The nude’s downward gaze and heavy-lidded eyes set a psychological temperature quite different from the flirtatious nudes of salon painting. There is introspection, perhaps fatigue; there is also a boundary the viewer is not invited to cross. The painting’s ethics are embedded in its form. The black lines assert the painter’s choices without caressing; the gold ground holds the body like a field rather than a bed; the white cloth shields without hiding. The result is a look that is frank but not prying, analytic but not cruel. We are asked to consider how painting can attend to a body without turning it into spectacle.

Influence on Sculpture and the Feedback Loop of Making

Matisse’s engagement with sculpture around this time—culminating in the “Back” series—creates a feedback loop with works like “Nude (Black and Gold).” The painting thinks like a sculptor, building volume by decisive planes and treating the frontal pose as a problem of relief. Conversely, the boldness of the brush and the liberty of the painted contour seem to inform his sculptural simplifications. The exchange across mediums strengthens both, and this canvas is one of the places where the dialogue is most legible.

Why the Painting Still Matters

The work endures because it demonstrates, with absolute economy, how a painter can transform a narrow set of means into inexhaustible sensation. A handful of colors, a handful of lines, and the conviction to stop when the relation is right—these are the lessons it offers. For artists, designers, and viewers today, the painting proposes a counter-model to both photographic exactitude and ornamental excess. It argues for power through clarity, and for feeling produced by structure rather than sentiment.

Conclusion

“Nude (Black and Gold)” is a compact manifesto. The body is simplified but weighty, frontal yet alive, dignified without narrative adornment. Black becomes the instrument of form, gold and green the planes of atmosphere, white the measured accent that tunes the whole. Brush and contour are never idle; every mark carries structural work. In the balance between rawness and order, immediacy and respect, Matisse arrives at a modern nude that is neither academic nor sensational. It stands as one of the most concentrated demonstrations of his 1908 ambition: to distill seeing into relationships of color and line that feel inevitable, humane, and unforgettably present.