Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

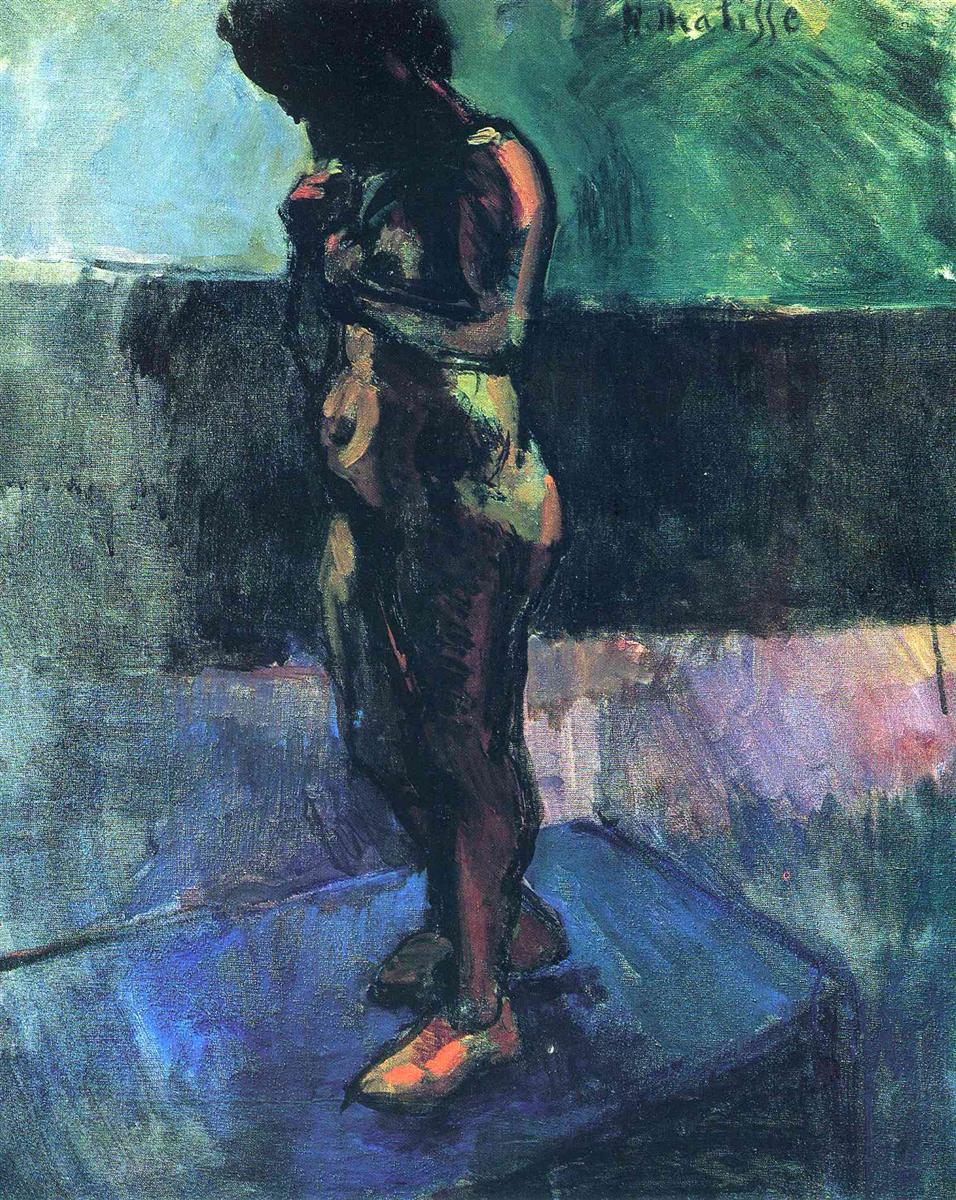

Henri Matisse’s Nude Wearing Red Shoes (1907) is a surprising, inward-looking canvas from the same year he painted some of his most extroverted Fauvist works. A single standing figure occupies a shallow studio—nearly a silhouette—while a pair of small red shoes flashes at the base like punctuation. The body is modeled in dark greens, violets, and umbers, set against a luminous field of teal and a cool, blue-violet platform. Instead of dazzling with saturated daylight, Matisse builds a nocturne: a study of weight, balance, and interior mood where color deepens into shadow and the nude feels carved by light. The result is a quiet but forceful statement about how a modern figure can command space without theatrical pose or elaborate setting.

Historical Context

The year 1907 marks a turning point in Matisse’s search for a synthesis between Fauvism’s audacious color and a more architectonic treatment of form. In the wake of Collioure and the bright Mediterranean canvases, he began tempering chromatic exuberance with structural clarity, engaging sculpture more intensely and simplifying bodies into large planes. Nude Wearing Red Shoes sits squarely within this pivot. It retains color’s authority, but pressed into service of volume rather than spectacle. Across Paris, artists were reassessing the figure—flattening space, hardening contours, and looking to non-Western sculpture for essential shapes. Matisse’s answer here is not fracture or aggression but a somber poise that lets line and low-key color construct presence.

Composition and Spatial Design

The figure stands near center, slightly turned to the right, head bowed and hands lifted toward the chest in a small, private gesture. She rests on a raised platform whose front edge runs diagonally from lower left toward the right, tilting the space and making the stage tangible. A horizontal seam divides wall and lower field, compressing depth and pressing the nude forward. The background is almost abstract: a cool teal upper register and a darker belt of green-black that reads as a horizon line or wainscot. The platform—painted in blue-violet and hemmed with darker strokes—anchors the body as decisively as a plinth supports a statue. The composition feels sculptural because the surroundings act like a studio box—pared down to essentials so the eye tracks mass, balance, and silhouette.

Color and the Architecture of Light

The palette is restrained: teal and blue-violet for the room, deep greens and umbers for the figure’s shadowed planes, and a few emphatic notes—citron highlights on calf and breast, rose along the foot, and the two small eruptions of red at the shoes. Matisse refuses academic chiaroscuro; instead, he lets color value and temperature do the modeling. Dark, cool mixtures carve recessions; warmer, higher-value strokes strike where the form turns toward light. Because the room’s light is generalized rather than directional, the body reads like an accumulation of planes, each one a decision about how color can declare volume. The overall effect is atmospheric and interior, a deliberate counterpoint to the sun-washed exteriors of the same period.

The Red Shoes as Motif

The titular shoes are tiny yet decisive. They puncture the low register with warm accent, pulling the viewer’s gaze to the ground where weight meets support. Their redness does not decorate; it balances. The composition gathers intensity at the feet—where the figure’s stance is negotiated—and the shoes make that negotiation visible. They also inject a human specific into an otherwise archetypal nude, introducing the unorthodox idea that a classical body might stand on a plinth wearing contemporary footwear. This incongruity jolts the genre, suggesting a studio moment rather than a mythological scene and tethering the monumental body to lived detail.

Gesture, Balance, and Poise

The figure’s gesture is inward. Head inclined, shoulders slightly curled, hands lifted near the chest, she reads as self-contained rather than displayed. The stance is nonetheless stable: one foot slightly advanced, the other back and toed outward, knees softened, pelvis settled over the platform’s diagonal. These small adjustments distribute weight convincingly. Matisse’s interest is less in sensuality than in the ethics of balance—how a living body composes itself in space. The shoes, again, intensify this theme; we feel the pressure of the toes and the grip of the sole against the platform, the points at which the body and world test one another.

Contour and Modeling

Black and very dark green contours cut decisive edges around limbs, flank, and profile. The lines thicken at joints and thin along straights, acting like the lead of stained glass to contain and energize the color fields. Within those fields, modeling occurs in broad, directional swathes, often turning abruptly rather than melting gradually. A thigh pivots from violet-black to olive; the torso’s plane lifts from deep green to a sudden, warm ocher. The face, partly submerged in shadow, presents a mask-like reserve: the bridge of the nose and cheekbone announced by a few pale strokes against darkness. This economy of means creates an impression of mass without descriptive fuss.

Brushwork and Surface

The painting’s surface is alive with varied touch. The background’s teal is brushed in broad, semi-transparent layers that allow undercolor and canvas tooth to breathe through, giving the air a slight shimmer. The dark belt across the middle is denser, a nearly flat slab that pushes the figure forward. On the body itself, the brush often follows anatomical direction—the length of a calf, the arc of a rib—so that strokes become cues for form. Around the feet and platform, Matisse drags blue-violet in long, sweeping pulls, then breaks it with darker ridges to suggest edge and shadow. The cumulative effect is direct and unlabored; one senses decisions made at speed and left visible rather than corrected into smoothness.

Space, Stage, and Studio

The room reads as a studio stage rather than a descriptive interior. The platform—its front edge emphasized and its top simplified to a single plane—acts as a plinth. The horizontal seam across the wall stabilizes the composition like a horizon in a landscape. This architecture of planes allows Matisse to keep the figure monumental while maintaining modern flatness. The viewer knows where the body stands without recourse to detailed perspective; the measured geometry of platform and wall is enough to hold the pose in believable space.

Mood and Psychology

Despite the painting’s structural rigor, its mood is palpable. The bowed head and gathered hands suggest introspection or modesty; the darkened face deflects invasive scrutiny, encouraging a contemplative rather than possessive gaze. The near monochrome of the room deepens the sense of quiet, as if sound were dampened. The red shoes introduce a spark of individuality—a note of the sitter’s agency—without compromising the painting’s calm. The psychology arises from pose and color rather than from facial expression, consistent with Matisse’s broader move in 1907 to let form carry emotion.

Dialogue with Sculpture

The figure feels carved. Planes meet decisively; mass reads by abrupt turns rather than soft transitions. This sculptural grammar aligns with Matisse’s engagement with relief and his study of simplified, mask-like heads and torsos. The platform functions almost as a pedestal, encouraging the viewer to read the body as a three-dimensional object presented for sustained looking. Yet paint adds what stone cannot: the chromatic breath of teal and violet that softens the severity and lets darkness glow rather than merely absorb.

The 1907 Modern Turn

In 1907 many artists tested alternatives to naturalistic representation. Nude Wearing Red Shoes shows Matisse choosing clarity over fragmentation. Space is shallow but coherent; the body is simplified but weighty; color is bold but not loud. The painting embraces reduction—few objects, few hues—so that the viewer can attend to the core questions of figure painting: how a body stands, how light constructs volume, how contour dignifies a form. It is a manifesto in minor key, distinct from the bright declarations of the same year yet essential to the arc that leads to the great decorative panels.

Light, Shadow, and Temperature

Light in the canvas is generalized and cool. Instead of a beam that casts firm shadows, there is an ambient glow that permits patches of warmth to register as events: a lemon flare on the instep, an ocher note along the breast, a warm reflection near the thigh. These warm incidents operate like chords resolving within a cool key. They also prevent the figure from dissolving into the background, giving the eye places to land as it climbs the body from foot to head.

The Signature and the Frame

Matisse places his signature at the upper right, small but legible against the teal field. It sits inside the painted world rather than detached along the border, reinforcing the idea that the background is a constructed plane. The frame of the composition—especially the upper and right edges—presses close to the figure, cropping negative space and heightening immediacy. The viewer stands at studio distance, not across a room, reinforcing the intimate, worklike mood of a session between painter and model.

Gender, Gaze, and Agency

Nude figures often risk sliding into displays arranged for a possessive gaze. Here, several choices resist that tendency. The bowed head and shadowed face limit psychological overexposure; the strong contour dignifies rather than titillates; the red shoes, oddly practical, read as the model’s own detail rather than a prop to entice. The painting honors the body as an intelligent structure—a human presence inhabiting a stance—rather than presenting it as a soft spectacle. In this sense the canvas is consistent with Matisse’s broader ethical stance: intimacy without violation, clarity without prurience.

Comparisons within the Oeuvre

Compared to the blazing sunlight and decorative gardens of works like The Blue Nude (Souvenir of Biskra) painted the same year, Nude Wearing Red Shoes is a nocturne. It shares with his 1907 Nude Study the sculptural gravity and limited palette, but the mood here is quieter, more interior. The platform and studio box point forward to the interiors of the following decade where color planes would become walls, floors, and patterned screens; the insistence on contour anticipates the distilled edges of the late paper cut-outs. Seen across the career, this painting stands as a keystone linking the early Fauvist blaze to the later architectonic calm.

Materiality and Viewer Experience

The painting rewards close looking. One sees the scumble of teal drifting over darker underlayers, the ridges where black contour pooled, the drag of the brush that leaves the platform’s edge slightly frayed. These marks make the act of painting present, inviting the viewer to reconstruct the sequence of decisions: blocking the room, placing the platform, staking out the figure’s contour, and then tuning planes of color to coax volume. From a step back, these traces consolidate into clarity: a body poised in a studio, alive with soft, cool light and grounded by two quiet flames of red.

Legacy and Continuing Relevance

Nude Wearing Red Shoes persists as a lesson in how little is needed to create a convincing, modern figure. A handful of hues, a measured stage, a decisive contour, and one idiosyncratic detail suffice to build a world. For painters, it models an ethics of restraint: let color do structural work, let line tell the truth, let a single accent carry narrative force. For viewers, it offers a renewed way to encounter a nude—through balance, temperature, and touch—rather than through conventional seduction. Its quiet intensity remains as contemporary as the day it was made.

Conclusion

Matisse’s Nude Wearing Red Shoes is a study in sculptural poise and chromatic economy. The shallow studio, the blue-violet platform, the teal air, and the dark, modeled body create a calm arena where a single figure stands absorbed in her own presence. The small red shoes anchor her to the world and to us, humanizing the archetype. In 1907, this canvas helped Matisse chart a path beyond Fauvism toward a modern classicism grounded in line, plane, and the disciplined power of color. It is a quiet painting with an enduring voice, reminding us that monumentality can whisper.