Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

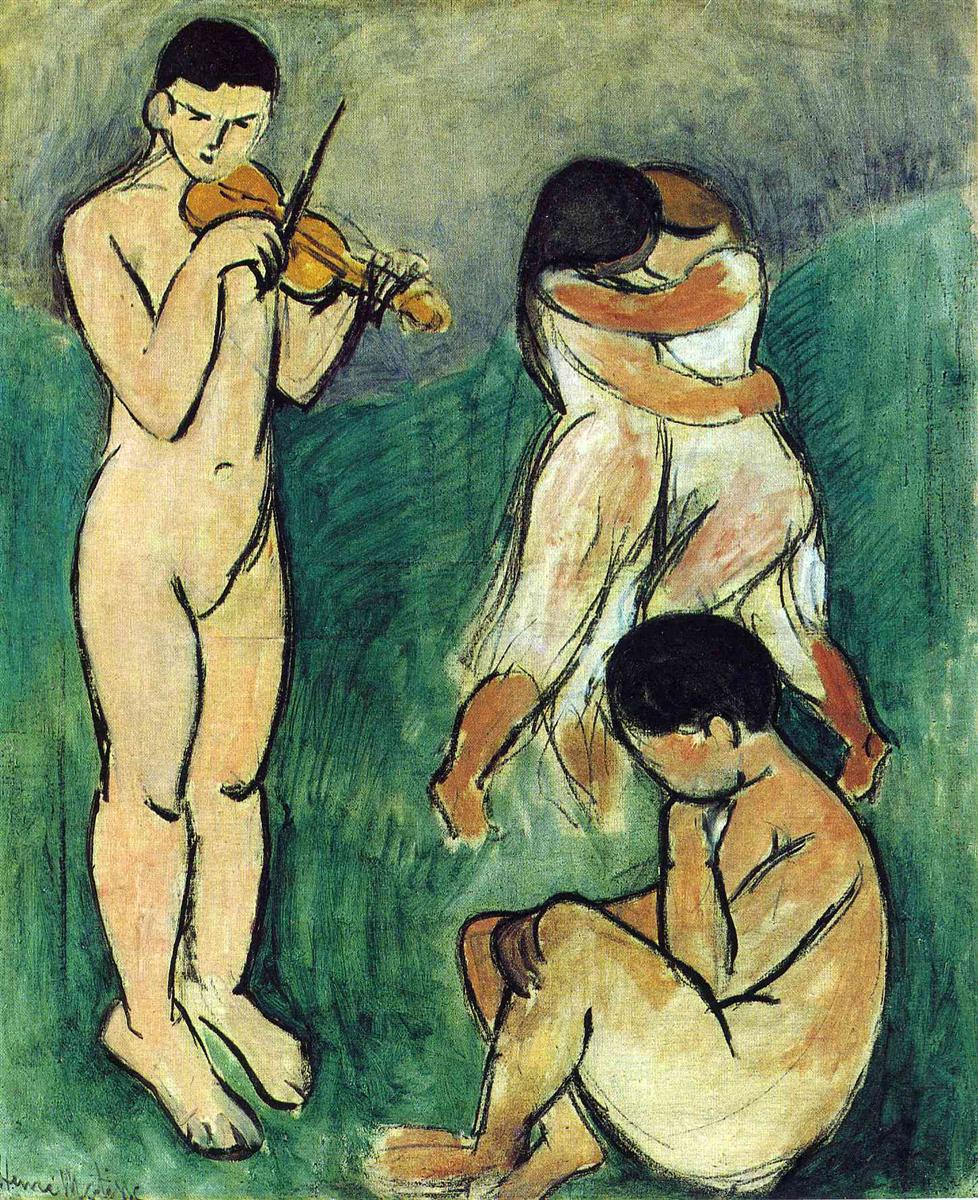

Henri Matisse’s Music (Sketch) (1907) is a compact manifesto about how sound, movement, and human presence can be translated into paint. Four figures inhabit a shallow green field: a nude youth plays the violin at left, a pair of lightly draped dancers twirl in an embrace near the center, and a seated child curls inward at the lower right. The background is reduced to broad, vibrating fields of bluish green and gray, while strong black contours simplify anatomy to essential curves. What looks at first like a rough study is, in fact, a lucid proposal for a new kind of figure painting—one in which rhythm is the true subject and where color and line do the work that narrative once did. Placed at the hinge year of 1907, the work anticipates Matisse’s monumental explorations of rhythm and communal harmony that would culminate a few years later.

Historical Context

By 1907, Matisse had already shocked Paris with Fauvist color, only to pivot toward a more structured modernism. He was searching for a synthesis: retain the freedom and intensity of color and brushwork while granting figures a statuesque calm. At the same time, European art was in upheaval; painters probed non-Western sources, simplified anatomy, and questioned the deep spatial box inherited from the Renaissance. Music (Sketch) belongs to this turn. It replaces the anecdotal scene with an archetype—music as a social energy that gathers bodies into relation. The painting can be read as a stepping-stone toward the large decorative panels of 1910, where music and dance become secular myths of collective joy. In the sketch we watch Matisse testing how few means are needed to make rhythm visible.

Subject and Motif

The subject is disarmingly simple: four youths, three nude and one draped, inhabit a bare ground. One plays, two dance, one listens inwardly. The violinist’s focused expression, the dancers’ entwined arms and stepping legs, and the crouching child’s folded pose create a spectrum of musical responses—making, moving, and contemplating. There is no setting beyond color; no architecture, trees, or furniture tether the figures to a specific place. The scene is less an event than a state of being, a timeless distillation of how music organizes people in space.

Composition and Spatial Design

Matisse composes the figures as a triangle that stabilizes the surface while generating movement. The violinist forms the tall left pillar; the kneeling child provides a compact mass at the lower right; the dancers bridge the gap with a swirling knot of limbs and light drapery. The field is divided into two large bands: a bluish-green ground that occupies the lower two-thirds and a gray-green sky above. The meeting of these bands occurs behind the dancers’ heads, compressing space and pulling the group forward. There is almost no perspectival recession; instead, depth is suggested by overlaps and by the scale difference between the standing and seated bodies. The eye moves in a loop—from the violinist’s instrument, to the dancers’ embrace, down the arc of the white dress to the crouched listener, and back via the violinist’s legs. This circular itinerary mimics musical phrasing: tension builds, resolves, and repeats.

The Violinist

The standing youth at left acts as the composition’s engine. Matisse renders him with strong black contours and pale, unmodeled flesh, a taut column whose only complex detail is the violin and bow. His head tilts slightly toward the instrument; a furrow above the brow signals concentration. The bare feet plant firmly, and the weight distribution across the legs is just believable enough to anchor the figure. Because the violinist neither looks out of the picture nor toward the dancers, the scene feels self-contained; he is absorbed in playing, not in performance. The bold drawing of the instrument—orange-brown body, black outline, simplified f-holes—is one of the painting’s few chromatic accents, a visual “note” that the other bodies echo in their rhythm.

The Dancers

At center-right, two lightly draped figures lean into each other, arms thrown around backs and shoulders, faces touching in a blur. The dress, sketched with white pigment and swift black lines, becomes a device for showing motion: it sweeps diagonally, then dissolves into passages of thin paint that allow the green ground to show through, like air moving through fabric. Legs step apart and cross, and the paired torsos twist into a gentle knot. Matisse eliminates facial detail to keep the dancers anonymous and archetypal. Their union is less erotic than kinetic—a single body with two heads momentarily finding balance while the music turns.

The Seated Listener

The crouching child at lower right is the painting’s counterpoint. He is the nearest mass to the viewer, rendered in warm flesh strokes edged by black, chin tucked to hand as if listening inwardly. This figure grounds the composition physically and emotionally. Where the dancers externalize rhythm, the child internalizes it. He is the picture’s breath, the rest that makes the surrounding movement legible. The roundness of his back echoes the violinist’s bowed arm and the dancer’s shoulder, knitting the three figures into a single visual chord.

Color as Atmosphere

The palette is remarkably limited: bluish green for the ground, gray-green for the sky, pale flesh hues tinged with rose and ocher, black contours, and small accents of orange-brown in the violin. This restraint creates a meditative atmosphere. The green field is neither grass nor stage but sensation—a cool, continuous tone against which warm bodies resonate. The gray upper band suggests open air without insisting on clouds or sun. By avoiding complex local color, Matisse lets mood arise from harmony. The cool ground calms, the warm flesh animates, and the instrument’s brown punctuates like a low, steady note.

Contour and the Language of Line

Black contour is the painting’s backbone. It describes anatomy with a calligrapher’s economy: a single sweep for the outside of a thigh, a kinked stroke for a knee, a loop for an ear. The lines are not fussy; they thicken and thin, letting the brush’s pressure show. Contour, for Matisse in 1907, is not merely drawing; it is ethics and method. It rejects illusionistic modeling in favor of clarity. The black lines contain the color fields like the lead of stained glass, giving them dignity and structure. Where line is absent—across the dancers’ white dress—color bleeds into ground, and motion results.

Brushwork and Surface

Although this is a sketch, it is not careless. The paint is laid in with decision: broad scrubbed fields for the ground and sky, planes of thin flesh color where the canvas grain breathes through, and more opaque passages at joints and faces that require emphasis. The brushwork is directional. Sweeps moving diagonally up and right across the ground meet the descending diagonals in the dress; the two rhythm sets cross like musical voices. Occasional pentimenti—ghost traces where a limb was shifted—add to the sense of improvisation, as if the painter were composing in real time in response to an unheard music.

Space Without Illusion

Traditional figure groups are set on a stage with foreground, middle distance, and background. Music (Sketch) replaces that scaffolding with a plane. Depth is an agreement between figures rather than a mapped box. Overlaps do the work of distance: the dancers partly veil the sky band; the child overlaps the ground field at front; the violinist’s bow cuts into the dancers’ space without breaking it. The result is a space that feels both intimate and monumental—close enough for touch, open enough for archetype. This treatment anticipates the grand decorative panels where bodies float on continuous fields of color, stripped of furniture and horizon.

Music Made Visible

The painting’s most radical claim is that music has a visual grammar. It proposes that rhythm can be expressed by repeating shapes and by the choreography of masses. The bowed arm, the dancers’ entwined torsos, the child’s rounded back—each is a curved phrase answered by another elsewhere. The composition’s triangular order supplies meter; the sweeping dress and crossing bow supply syncopation; the limited palette supplies tonal key. Even the unpainted or thinly painted patches count as rests. In this sense, the canvas is less a depiction of people hearing music than a score that is music, legible to the eye.

From Fauvism to Structure

Compared with the riot of color in 1905, Music (Sketch) looks restrained, but its boldness lies in structure. Color is not an end in itself but a means to sustain clarity. The figures are simplified almost to silhouettes yet remain weighty and specific. This poise between reduction and fullness is Matisse’s 1907 breakthrough. By limiting hue and value, he allows contour and placement to carry expressive burden. The painting thus moves beyond Fauvism’s chromatic sensationalism into a calmer modernism that would shape his work for decades.

The Year 1907 and Modern Dialogues

Across Europe, 1907 marked a turn toward essential forms. Picasso’s experiments challenged the soft modeling of academic nudes. Matisse, rather than shattering bodies, chose to simplify and monumentalize them. Music (Sketch) shares with the broader modern movement a fascination with the “primitive” as a source of clarity—mask-like faces, sculptural torsos, and a flattening of space. But its mood is different. Matisse refuses alienation in favor of communal tenderness. The dancers touch; the child listens; the player concentrates. The painting’s modernity is not aggression but concord.

Gesture and Human Meaning

Every gesture here is archetypal. The violinist’s bent head signals devotion to craft. The dancers’ embrace signifies companionship and surrender to rhythm. The seated listener’s curled posture suggests contemplation and the inwardness music can induce. None of these gestures is melodramatic; they skirt the edge of symbol while staying rooted in believable anatomy. Matisse shows how slight shifts—an arm circling a shoulder, a chin lowering to chest—can carry large emotional weight when set against a simplified ground. The painting becomes a meditation on how art binds people: one makes sound, two translate it into motion, one translates it into thought.

The Sketch as Method

The word “sketch” can mislead. In Matisse’s practice, the sketch is a site of truth. It records speed, risk, and the artist’s changing mind. In Music (Sketch), the economy of means—the absence of detail, the thin skin of paint—does not indicate incompletion but relevance. The essentials are present: compositional balance, rhythmic counterpoint, chromatic tuning. The spareness invites the viewer to imagine the music in the painter’s studio and to sense the sequence of decisions that yielded these forms. Many of those decisions carry forward into later, more monumental canvases; the sketch is the seed where form and idea first cohere.

Light and Value

The painting resists dramatic light. There is no cast shadow or directional beam. Instead, value is used sparingly to articulate volume—the slight darkening at a knee, the line of a shoulder, the shadowed underside of a foot. This restraint keeps the figures from becoming sculptural illusions; they remain signs on a flat field. Yet the bodies never feel flimsy. Their weight is implied by contour and by the grounded whiteness of feet and shins against the green. Light in this world is even, akin to the steady illumination of a stage rehearsal where performers seek balance rather than spectacle.

The Ethics of Looking

Although nudity is prominent, the picture does not invite voyeurism. Faces are simplified, genitals are drawn without emphasis, and the mood is worklike rather than erotic. The violinist strives; the dancers practice; the listener concentrates. The spectator’s role is to witness a communal discipline rather than to possess bodies with the eyes. This ethics of looking was central to Matisse’s project: to celebrate the human form as a site of harmony and energy, not as an object for titillation.

Anticipations and Legacy

It is tempting—because it is true—to see Music (Sketch) as a precursor to Matisse’s later Music and Dance panels of 1910. Many building blocks are here: the limited palette, the flattened field, the chain of bodies arranged for rhythmic clarity, and the idea that simple gestures can stand for collective feeling. The sketch’s intimacy, however, has its own legacy. It reminds us that monumentality is born from quiet experiments where line and color are stripped to their essentials. The painting remains a touchstone for artists who seek to turn movement, sound, and social relation into abstract pictorial order.

Conclusion

Music (Sketch) condenses an entire philosophy of painting into a few bodies on a green field. Through black contour, a restrained palette, and a choreography of gestures, Matisse renders music visible. The violinist’s focus, the dancers’ embrace, and the child listener’s inward curl form a triad of making, moving, and contemplating. Space is simplified to planes; light is generalized; narrative is replaced by rhythm. In 1907, this was not merely preparatory work but a declaration: painting could be built from harmony and stillness without losing intensity. The sketch opens the path toward the great decorative panels, yet it stands complete on its own—as a serene, urgent testament to how art organizes human life into form.