Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

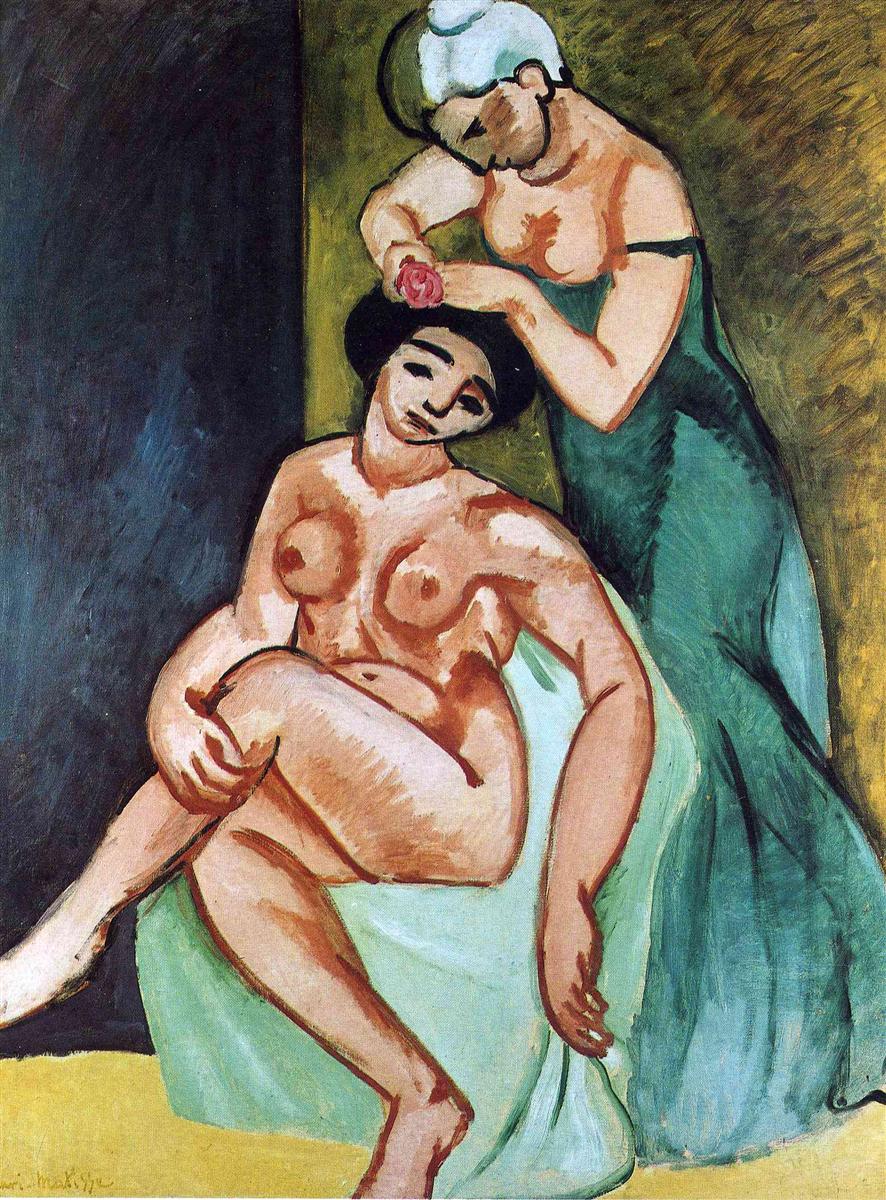

Henri Matisse’s Female Toilets (1907) sits at a pivotal moment in the artist’s development, when the exuberant color of Fauvism met a new commitment to structural clarity and sculptural form. The scene is intimate and domestic: one woman, nude and seated, receives a flower placed in her hair by another woman who stands beside her in a green gown. This everyday ritual of grooming becomes a stage for Matisse’s experiments with contour, flat planes of saturated color, and a compressed sense of space that pulls the figures forward. The painting is neither anecdote nor mere genre scene; it is a condensed meditation on tenderness, the power of color to shape emotion, and the modern reimagining of the female figure.

Historical Context

The year 1907 is a hinge year in European art. The shock of Fauvism—unleashed at the 1905 Salon d’Automne—had already placed Matisse at the forefront of avant-garde painting. Yet by 1907, the simple thrill of pure, unmixed color was no longer sufficient. Matisse was searching for a synthesis: how to preserve the freedom and intensity of Fauvist color while giving his figures a deeper stability and monumentality. In Female Toilets, this search is visible in the firm black contours that lock forms together, the simplified anatomy that reads like carved planes, and the deliberate, almost architectural placement of color fields that define the room. The intimate subject aligns with his broader interest, from these years through the 1910s, in everyday domestic interiors and the timeless rituals that connect them—reading, music, rest, and toilette.

The Meaning of “Toilette”

The title can be perplexing for modern readers. “Female Toilets” refers not to a bathroom but to the French notion of la toilette—the ritual of dressing, grooming, and adorning the self. Matisse approaches this ritual as an allegory of transformation and care. The rose being set into the seated woman’s hair turns the moment into a quiet ceremony. The title emphasizes process rather than identity; the figures are not individualized portraits but archetypes of repose and service, of being adorned and adorning, of receiving and giving attention.

Composition and Spatial Design

The composition operates on a triangle formed by the seated figure’s bent knee, the tilt of her head, and the standing figure’s torso. The seated woman forms a compact, circular mass; her crossed leg and curved arm echo each other, creating a contained rhythm that suggests self-absorption and inwardness. The standing figure, by contrast, is a vertical counterweight. Draped in green, she bends toward the other like a hinged column, a gesture that bridges the gap between bodies.

Matisse flattens spatial depth by setting the figures against large fields—a dark, nearly black panel at left, an olive-yellow wall to the right, a pale aqua drapery beneath the seated body, and a yellow floor at the bottom edge. These planes meet in abrupt seams rather than dissolving into perspectival recession. The result is a shallow stage where color fields are actors as consequential as the women themselves. The space is legible but compressed, an arena where the most important drama is the interplay of lines and hues.

The Role of Contour

One of the painting’s most striking features is the decisive use of black contour. The drawing is not hidden under modeling but brought to the surface; it functions like the lead lines in stained glass, containing and charging each patch of color. The outlines around thighs, shoulders, and faces are not tentative corrections—they are intentional boundaries that give the bodies weight and clarity. This approach allows Matisse to reduce anatomical detail without losing structure. Fingers become scalloped arcs; the seated figure’s breast is indicated by a few assertive strokes; the face is a mask of essential features. The black line dignifies these simplifications, insisting that expressiveness can come from restraint and economy.

Color as Emotional Architecture

Matisse’s palette here is reduced yet charged: olive and mustard tones in the background, an array of greens from sea-foam to viridian, ochres and warm pinks in the flesh, and deep black accents. Each color supplies an emotional temperature. The green of the standing woman’s dress is cool and stabilizing, like a column of shadow. The flesh tones of the seated figure are warm and varied, veined with strokes that move between rose, sienna, and white. The black of hair, eyes, and contours acts as an intensifier that makes adjacent colors vibrate.

Crucially, the colors are laid down in flat, confident patches that deny academic shading. Highlights are often literal white paint rather than carefully blended tones. This gives the body a luminous, almost ceramic presence, and it underscores one of Matisse’s convictions: that color can model form just as convincingly as light-and-shadow modulation, provided the contours are strong and the relationships between hues are carefully tuned.

Gesture, Touch, and the Drama of Care

The heart of the scene is the exchange of touch. The standing woman’s hand presses a rose into the seated woman’s hair—a tiny red accent that acts as a compositional pivot and a narrative climax. The seated figure’s head tilts, eyes half-closed, in a posture of trust and receptive stillness. This dyad of giving and receiving is emphasized by the divergence of their states of dress: one clothed, active, and vertical; the other nude, passive, and inward. Matisse neither eroticizes nor moralizes this contrast. Instead, he suggests a social and emotional relationship—perhaps companionship, perhaps the practiced choreography of a housemaid and her mistress—without turning the figures into types. The painting’s tenderness resides in this ambiguity: it is at once a private scene and a universal act of care.

The Nude Reimagined

Matisse’s nude is not the cool marble ideal of the academy nor the voluptuous odalisque of nineteenth-century Orientalism. It is a modern, constructed form, assembled from planes and curves that privilege essential rhythm over descriptive detail. The crossed leg creates a dynamic zigzag from knee to elbow to breast, while the belly and thigh are rendered as wide, confident arcs. The labors of observation—weight, gravity, balance—are fully present, yet the simplifications declare that this is not anatomy for its own sake. The body becomes a site for exploring harmony and tension: how a bent elbow can echo the arc of a knee, how a dark hair mass can balance a green drapery, how a downward-tilted face can lend a whole canvas its mood.

Fauvist Roots and the Turn Toward Structure

In the first Fauvist years, Matisse shocked viewers with violently non-naturalistic color. By 1907, he began tempering that audacity with an interest in architectonic form. Female Toilets sits at this juncture. The brushwork remains broad and visible, refusing polished finish, yet the composition is disciplined. The left vertical of the dark wall functions like a proscenium; the diagonal fall of the green garment introduces movement; the yellow wedge of the floor anchors everything. Even the drapery under the seated figure is more support than ornament, a pale plane designed to push the warm flesh tones forward. This balance between coloristic freedom and compositional order would sustain Matisse through subsequent decades.

Dialogues with 1907 Modernism

The year 1907 is also associated with a turn to so-called “primitivism” and the breakdown of classical representation. While Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon assaults the viewer with fractured forms, Matisse chooses intimacy rather than rupture. The mask-like simplifications of the faces in Female Toilets acknowledge the same global sources and the same appetite for reduction to essentials, yet Matisse directs those energies toward calmness and poise. Where others pursued dislocation, he pursued harmony—an equilibrium built not from imitation of Renaissance depth but from the modernist orchestration of flat color fields.

The Psychology of Interior Space

Matisse’s interiors often propose that rooms can be psychological states. Here, the dark vertical to the left resembles a curtain or void; the olive wall to the right, streaked with green, feels like a living atmosphere rather than mere backdrop. The yellow patch of floor glows as if sunlight were pooled there. The spatial cues are minimal, yet they conjure a setting that is both specific and dreamlike. The figures seem safely enclosed, shielded from the world’s turbulence, and the ritual of toilette becomes a meditative pause. The viewer is invited not to intrude but to witness, to adopt the painting’s own tempo of unhurried attention.

Materiality and Brushwork

Close inspection reveals how physically present the paint is. Brushstrokes retain their edges; they stack and overlap like laid tiles. The flesh is especially built up with directional strokes that follow the curvature of limbs, allowing the paint itself to describe volume. Matisse frequently leaves slight gaps where contour and color do not perfectly meet, a deliberate breathing space that keeps the image vibrant and alive. The effect is a paradoxical combination of immediacy and deliberation: the decisions are swift, but their orchestration is meticulous.

The Rose as Pictorial Keystone

The small rose placed in the seated woman’s hair is a miniature masterstroke. Chromatically, its warm red sits between the flesh pinks and the cooler greens, acting as a hinge between the two dominant color families. Compositionally, it marks the point where the standing figure’s downward energy meets the seated figure’s inward turn. Symbolically, it crowns the ritual, transforming grooming into adornment. The rose is a whisper rather than a shout, yet without it the painting’s emotional structure would be less complete.

Gender, Ritual, and Modern Intimacy

Rather than presenting the female body as a spectacle for a male gaze, Female Toilets maps a field of female intimacy and labor. The standing woman’s role is active and skilled; the seated woman’s role is receptive and trusting. The scene suggests a continuum between service and friendship, routine and celebration. It honors the kinds of care work that often go unrecorded in grand history paintings. By monumentalizing this quiet moment, Matisse argues that modern life’s deepest dramas may occur not on public stages but in rooms where people attend to one another.

Lineage within Matisse’s Oeuvre

The painting connects backward to the bold color and pastoral reveries of Le Bonheur de Vivre and forward to later interiors and odalisques where patterned textiles, furniture, and screens would frame nudes with decorative splendor. Here the ornament is restrained—the green dress, the pale drapery, the yellow floor—so that the relationship between two bodies remains central. The work also rhymes with other Matisse figures from around 1907 in which he explored a more massive, almost sculptural solidity. The simplifications employed here would later permit even more radical reductions, from the paper cut-outs of the 1940s to the monumental nudes of the 1930s.

The Expressive Mask

The faces are quiet but not blank. They operate like masks that condense emotion into a few essential signs: closed or heavy-lidded eyes for the seated figure; a downward, concentrating gaze for the standing figure. This mask-like treatment resists the anecdotal. Instead of capturing a fleeting expression, Matisse offers an enduring mood—serenity mixed with attentiveness—that radiates through the whole canvas. The mask also serves a functional role, granting the face the same simplified dignity given to limbs and torso so that no single element overwhelms the pictorial balance.

Rhythm, Repetition, and Visual Music

Matisse often described painting as analogous to music, and Female Toilets supports that claim through repetition and counterpoint. Notice the echo between the curve of the seated woman’s left arm and the droop of the green garment; observe how the arc of the standing woman’s back repeats, at another scale, the arc of the seated knee. These repeating shapes create visual chords, harmonies that bind the composition. The black vertical at left supplies a steady bass note; the yellow floor adds a bright treble; the rose functions like a brief melodic accent. The painting’s calm is not static; it is the equilibrium of elements tuned against one another.

Light Without Illusion

Although light is present—it strikes the top of the seated thigh, the shoulder, the crown of the head—Matisse uses it sparingly, more as a way to articulate forms than to produce optical illusion. White paint operates as light’s proxy, declaring highlights openly rather than dissolving them through careful chiaroscuro. This approach keeps the surface honest and prevents the scene from retreating into the deep space of classical illusionism. It also keeps the viewer’s attention on relationships at the surface: where warm meets cool, where line meets plane, where gesture meets rest.

The Ethics of Looking

There is a moral dimension to how the painting asks us to look. We are made witnesses to a private act, yet the image does not invite voyeurism. The seated figure’s closed eyes and the standing figure’s focused hands create a circle of attention that does not depend on the viewer’s gaze. We are permitted to observe but not to command. The strong contours and simplified faces, by deflecting psychological probing, help maintain this respectful distance. In a period when images of women were often coded for display, Female Toilets models an alternative: intimacy without possession.

Legacy and Continuing Relevance

The painting’s fusion of tenderness and formal rigor remains instructive for artists and viewers. It demonstrates how a limited palette can be abundant, how simplified forms can be monumental, and how an everyday act can carry archetypal weight. In the broader story of modern art, Female Toilets illustrates a crucial path: the move from the sensational novelty of Fauvist color toward a poised, architectonic modernism where harmony is achieved by the orchestration of flat shapes and decisive lines. The work also anticipates later conversations about care, labor, and domestic space—conversations that continue to give the painting fresh resonance.

Conclusion

Female Toilets distills Matisse’s 1907 ambitions into a small, potent drama of touch and color. The scene’s simplicity—two women, a rose, a shallow room—belies its complexity. Through contour that clarifies without hardening, through color that breathes emotion into structure, and through gestures that translate routine into ritual, Matisse transforms a moment of toilette into a timeless meditation on care and repose. The painting offers a modern vision of the figure that is not about spectacle or narrative but about the deep harmonies that can be drawn from line, plane, and hue. In its quiet way, it is a manifesto for what Matisse would continue to seek: a painting that is at once profoundly calm and profoundly alive.