Image source: wikiart.org

First Encounter: A Bouquet That Breathes

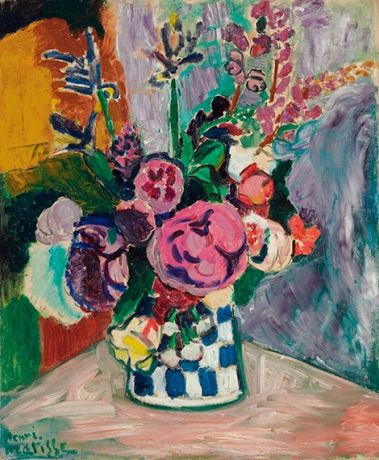

Henri Matisse’s “Peonies” from 1907 is a still life that behaves like a living presence. The blossoms surge upward in a checked vase, their rounded heads pressing gently against one another like actors gathered at the lip of a stage. Color refuses to sit quietly; it thrums in pulses of magenta, rose, violet, and coral, all encircled by decisive strokes of green and midnight blue. Rather than describe each petal meticulously, Matisse composes with parcels of paint, letting saturated daubs and swathes become the language of fullness, fragrance, and bloom. The bouquet feels freshly arranged, as if a hand has just set the vase down on the pink tabletop that angles toward us like an invitation.

The Moment of 1907 and the Evolving Fauve

Dating from 1907, “Peonies” sits at a pivot in Matisse’s development. Two years earlier, his 1905 canvases ignited Fauvism with their electric primaries and audacious disregard for naturalistic color. By 1907 he retained that chromatic boldness but tempered it with a more deliberate structure. In this picture, the feverish mosaic of tiny strokes that animated his Collioure landscapes yields to larger, assertive shapes. Black and dark contour return not as a cage but as a clarifying seam, describing rims, leaf edges, and the checkered geometry of the vase. The result is a still life that is both decorative and architectonic, both spontaneous and composed—evidence that Matisse was turning raw color into a disciplined grammar.

Composition: A Theater of Planes

The composition is triangular at heart. The tabletop forms the base, tilted just enough to lift the bouquet into our space without destabilizing it. The vase anchors the center, and the blossoms fan outward to form a generous apex that grazes the picture’s upper registers. This triangular arrangement stabilizes the exuberant brushwork. Matisse complicates the geometry with counter-movements: stems tilt diagonally; blossoms curl left and right; slender spikes of purple flowers lance upward like exclamation points. The checkerboard vase introduces a small grid—cool, crisp, and patterned—that sets off the soft, rounded blooms. The eye travels from the bright foreground corner to the vase’s blue-and-white rhythm, then up through the bouquet and back into the mottled backdrop, returning at last to rest in the pale pink plane of the table.

The Architecture of Color

Color builds the bouquet as surely as stems build it in nature. Matisse orchestrates a conversation between warms and cools: the pinks and reds pulse against the surrounding aquas and teals; violet shadows temper the heat; viridian and sap greens tuck into the bouquet like restful breaths. There is no single “light source.” Instead, luminosity emerges from the juxtaposition of high-chroma notes with quieter, chalkier passages. The white checks on the vase, thickly painted, flare against the blue squares to create a cool glow, which in turn heightens the warmth of the peonies. Throughout the canvas Matisse relies on temperature shifts—cool lilac beside a coral rose, mint green next to plum—to model form without conventional shading. The blossoms feel spherical because warm and cool brushstrokes curve around them like bands of weather.

Brushwork and Material Presence

“Peonies” is unapologetically painterly. You can sense the drag and lift of the brush, the density of impasto where Matisse insisted on a highlight, the scumbled transparency where undercolor breathes through. Petals are articulated with small, comma-like strokes that cluster densely near the core and fan outward more loosely at the periphery. Leaves are indicated with longer, blade-like pulls that end in a slightly frayed edge, mimicking serrated margins without literal depiction. The tabletop is brushed in broader sweeps of pink and salmon, their direction shifting just enough to suggest a plane turning in space. Throughout, the paint asserts itself as a physical substance; the bouquet seems to bloom from the very viscosity of oil.

Pattern, Ornament, and the Checked Vase

Matisse often used pattern as a structural device, and the checked vase in “Peonies” epitomizes that practice. Its blue-and-white grid is crisp and regular, a man-made order set against the organic tumult of petals and leaves. This contrast heightens the sensation of life: the flowers appear more luxuriant because the vase is so rational. At the same time, the check pattern echoes the geometry of the canvas itself—a rectangle filled with smaller rectangles—quietly marrying object and support. The pattern’s cool palette steadies the high-key blossoms and creates a chromatic bridge to the cooler blues and lavenders that animate the background.

Background as Atmosphere, Not Void

Rather than push the bouquet forward against a neutral field, Matisse opens the backdrop into a subtle environment of color. Mauves, lilacs, sea-greens, and soft greys swirl into one another, leaving hints of curtain, wall, or hanging textile without pinning them down. A passage of orange at left and an amethyst swell at right frame the bouquet like stage drapes. This chromatic envelope is crucial: it prevents the flowers from floating and spares the painting from decorative flatness. The background behaves like air saturated with color, the sort of radiant atmosphere Matisse prized because it lets objects glow from within rather than merely reflect an external light.

Peonies as Motif and Metaphor

Why peonies? For Matisse, the flower was not only a botanical subject but a way to test volume through color. Peonies are spheres of layered tissue; they invite the painter to build roundness with curving strokes and temperature shifts. In broader cultural histories, peonies carry meanings of abundance, renewal, and sensuality—associations that suit an artist devoted to the pleasures of sight. Their large, perfumed heads embody the very idea of pictorial generosity, what Matisse famously called “an art of balance, of purity and serenity.” In “Peonies,” that serenity is not the serenity of quiet monochrome but of harmony achieved amid sumptuous variety.

Drawing With Color and Contour

Look at the way Matisse draws the bouquet. There is almost no preliminary line; drawing happens in the act of laying color. Dark accents—deep blues and inky greens—function as contours when needed, pinching a petal here, carving a crease there, but they never become rigid borders. This method keeps forms supple. The bouquet reads convincingly as a cluster of individual blooms, yet the whole also coheres into a single breathing mass. Where some petals require an edge, Matisse gives it; where the volume must remain open, he lets atmosphere swallow contour and trusts the viewer’s eye to complete the shape.

Space, Depth, and the Tilted Table

The tilted tabletop is a characteristic Matisse device, tilting space toward the viewer without resorting to heavy perspective. Edges converge gently, and color depth does the rest. The front lip of the table is a firmer, warmer pink; as it recedes, the pink cools, and strokes align horizontally, allowing the vase to feel firmly planted. The bouquet occupies a middle zone, while the background breathes behind it in softened edges. No single rule of perspective governs; rather, local cues—overlaps, tonal adjustments, changes in edge—nudge the eye to read depth. The result is a space that feels believable yet clearly made, a crafted stage for color.

Rhythm and Gesture: The Dance of Stems

Matisse structures movement through rhythmic diagonals and arabesques. Stems sweep upward and outward in arcs that echo one another; blossoms tilt in sympathetic angles; thin spikes of delphinium-like flowers punctuate the top register with vertical accents. These gestures counter the solidity of the vase and the planar calm of the table. The bouquet does not sit; it sways. That sense of sway is crucial to the painting’s life. Even at rest, the flowers perform a choreographed dance of lines and masses, teaching the eye to move as they move.

Light Without Illusionism

Although the painting lacks conventional modeling, it glows. Matisse conjures light by pairing high-chroma notes with chalkier neighbors and by planting small fields of near-white to serve as internal lanterns. The white checks of the vase, the pale breast of a blossom, the soft cool notes in the background—all act as reflectors. These highlights are not placed according to a single, external light source; they are distributed to create balance and breathing room. What we experience as light is in fact a carefully tuned equilibrium between saturation and relief, between intensity and rest.

Dialogue With Matisse’s Other Still Lifes

“Peonies” converses with several still lifes from the same span. Compared to the explosive, pointillist “Parrot Tulips” of 1905, this canvas is calmer, its strokes broader and more sculptural. Compared to “The Geranium” of 1906, which explores a plant’s architecture with reflective cools, “Peonies” is more opulent and frontal, a deliberate celebration of abundance. It also anticipates later interiors—tables laden with fruit, jugs, and flowers set against patterned textiles—where Matisse perfects the art of letting pattern carry as much descriptive weight as object. Here, the checked vase serves that purpose, a modest prelude to the riot of pattern that would soon come.

Decorative Truth and Modern Vision

Matisse often championed the decorative as a pathway to truth. In “Peonies,” decoration is not trivial surface but a disciplined arrangement of color-shapes that yields clarity and pleasure. The bouquet’s decorative charm is inseparable from its structural intelligence. Color blocks fit together like a stained-glass window, yet the image never petrifies. It remains fresh because Matisse keeps edges lively, allows strokes to speak, and balances every saturated assertion with a quieter echo nearby. The painting proposes that modern vision can be both abstractly organized and sensuously charged.

Emotional Temperature and Viewer Response

The emotional temperature here is warm-joyful rather than feverish. The bouquet is exuberant, but the painting is not frantic; the checked vase and steady tabletop keep the mood grounded. Many viewers report a bodily response to such a work: the eyes slow down, the breath deepens, and one senses a lift in the chest—the same lift that comes from walking into a room where fresh flowers stand in a shaft of light. Matisse channels that everyday uplift into paint, making it reproducible wherever the canvas hangs.

Material Clues and Time in the Studio

Close inspection suggests an iterative process. Certain petals carry traces of underlying hues, evidence of adjustments as Matisse sought the right balance of warms and cools. The background’s layered color implies sessions of painting and repainting, building an atmospheric field that is neither muddy nor thin. The vase’s check pattern is likely laid with a steady hand after the bouquet had declared its proportions, which is why it sits so securely at the composition’s heart. These choices reveal a painter who trusted revision and who allowed the painting to find its equilibrium over time.

Cultural Echoes of the Peony

Peonies hold a long history across cultures—from Chinese painting, where they symbolize prosperity and honor, to European gardens where their late-spring bloom marks a season’s crest. Matisse, a collector of textiles and an attentive student of non-Western ornament, would have known peonies both as living flowers and as patterns on fabrics and ceramics. “Peonies” seems to absorb those legacies: the blossoms read at once as botanical and as motifs, luxurious objects and rhythmic signs. The checkerboard vase could easily be a piece of painted pottery from a coastal market, folding everyday craft into high art.

Lasting Significance

“Peonies” endures because it crystalizes a key Matissean proposition: that color, honestly deployed, can stand in for the fullness of experience. The canvas marries decorative splendor to structural clarity, producing a still life that is anything but still. Its blooms keep opening for the attentive viewer. The painting belongs to the sequence that leads from Fauvist rupture to the serene syntheses of the 1910s and, decades later, to the cut-outs where color and shape become the entire story. In this bouquet we witness that trajectory already in motion.

How to Look, Slowly

Stand close enough to see the separate strokes that build a single blossom; then step back until those strokes fuse into volume. Let your gaze trace the checkerboard around the vase—notice how each blue square vibrates differently depending on its neighbor. Follow a single stem upward and feel how your eyes inhale as the stroke thins and the petal opens. Finally, take in the bouquet as a whole and notice the gentle sway that organizes the mass. This oscillation between part and whole is the essential pleasure of “Peonies,” and it is the way Matisse teaches us to see.

Conclusion: A Bouquet of Modern Painting

In “Peonies,” Matisse gives us more than flowers on a table. He stages an encounter with color as a living force, with pattern as structure, with brushwork as embodied gesture. The painting’s checked vase, tilted table, atmospheric background, and swelling blossoms join in a lucid harmony that rewards slow looking. It is an image of abundance made not by piling detail upon detail but by selecting and balancing essentials. The bouquet may wilt in life, but in paint it stays vivid, a perennial bloom of modern art.