Image source: wikiart.org

First Impressions: An Intimate Ritual Cast in Blue

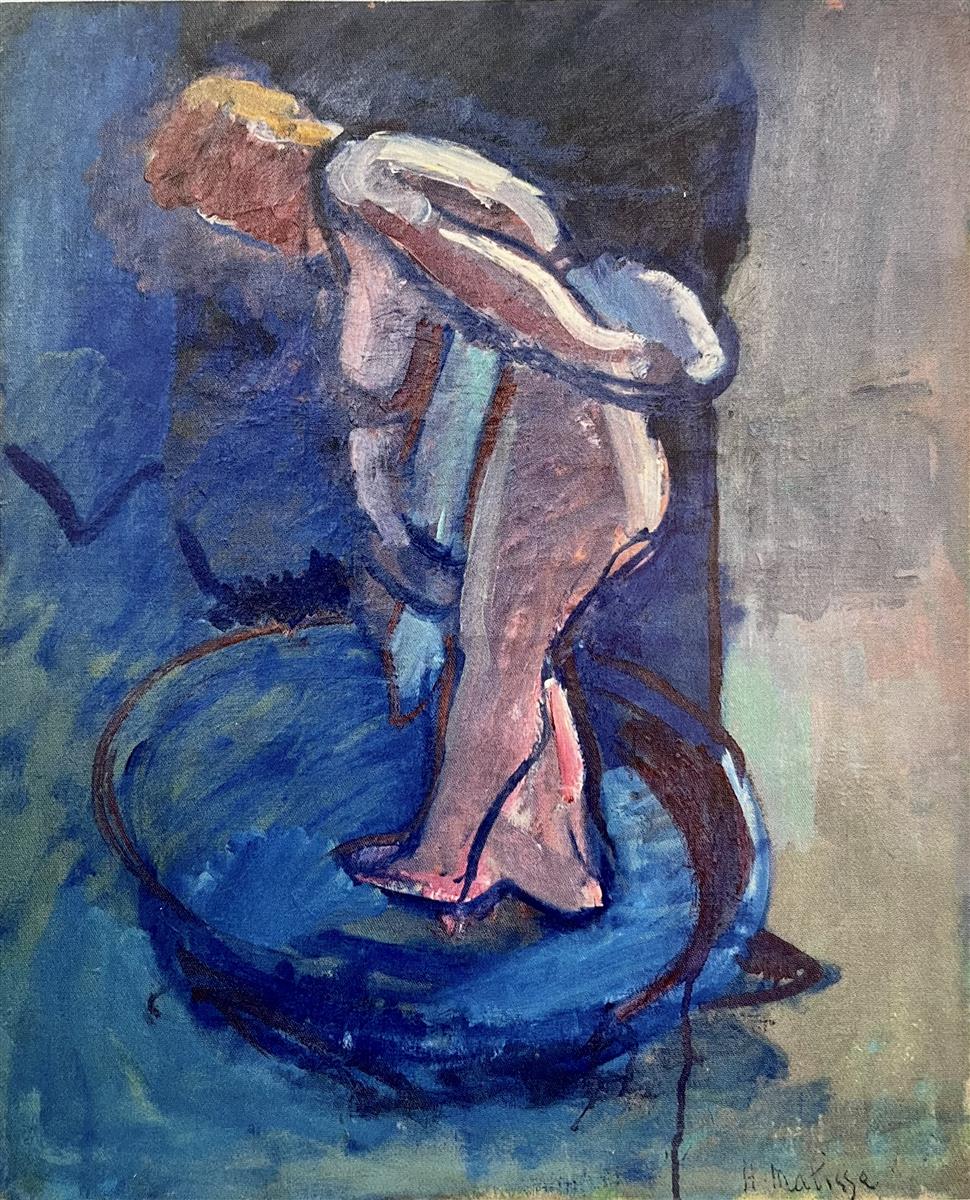

“Nude washing herself” (1907) presents a solitary figure bending over a shallow basin, her body haloed by thick, aqueous strokes of blue. The composition is spare and focused. There is no elaborate interior, no anecdote, only the essentials of a private act. The deep, saturated blues that flood the ground, basin, and surrounding space make the flesh appear almost incandescent by contrast, while dark linear contours carve the pose in swift, decisive movements. The result is a painting that feels at once direct and atmospheric, sculptural and fluid, intimate yet monumental.

The 1907 Context: Between High Fauvism and a New Structural Clarity

The year 1907 stands at a hinge in Matisse’s development. The shock of bold Fauvist color from 1905–06 had already transformed his palette, but he was now integrating that chromatic freedom with a more deliberate structural economy. He had been studying sculpture intently, modeling in clay and plaster, and that experience tightened his feel for weight, torsion, and contour. Works such as “Blue Nude” and the evolving series of bathers echo through the present canvas, where the body is simplified into sturdy planes and elastic outlines while color orchestrates space and mood. “Nude washing herself” belongs to this transitional moment: it retains the Fauvist intensity of hue but tempers it with the modernist drive toward clarity and essential form.

Composition: A Figure Encircled by Water and Color

Matisse organizes the composition around a few strong shapes. A broad oval basin sits like a ring or stage at the lower half of the canvas. Inside and just above it, the nude bends forward, head lowered, one leg stepping into the ellipse, the other poised at its edge. The S-curve of the spine leads the eye from the cropped head to the hips and down to the pointed foot, an arabesque that binds the composition into a single, continuous gesture. The basin’s oval is not merely a prop; it functions as a compositional anchor, echoing the arc of the back and concentrating attention on the action of washing. Surrounding all this is a field of blues—cobalt, indigo, and slate—modulated enough to suggest depth without descriptive detail. A vertical block at the right implies a wall or partition, but its purpose is primarily formal: it sets a hard, cool plane against the softer, swirling interior of the basin.

The Viewpoint: Slightly Elevated, Deliberately Cropped

The perspective is slightly elevated, allowing the viewer to see the oval of the basin clearly while maintaining the intimacy of a close vantage. The head is cropped high, and the hands dissolve into the act of washing rather than presenting themselves as anatomically complete forms. These decisions strip the scene of anecdotal distraction and emphasize the body’s architecture. The angle increases the sense that we witness a private moment from nearby, yet because the figure is framed by sweeping, simplified shapes, the intimacy never becomes voyeuristic; it is formalized into a ritualized pose.

Color Strategy: The World in Blue and Flesh

The painting’s drama arises from a disciplined palette. Blues dominate, performing multiple roles at once: they stand for water, shadow, and air; they mark the ground, basin, and ambient space; and they serve as the cool foil against which the body’s warm notes vibrate. Matisse modulates these blues with extraordinary sensitivity—some passages are transparent washes, others dense and velvety, others brushed with rapid, choppy strokes that suggest ripples. Against this sea of cools, the figure’s flesh is an orchestration of rose, peach, and pale lavender mixed with cooler notes along the shaded flanks. The meeting of warm flesh and cold water is not described with academic gradations of brown and gray; it is enacted as a temperature contrast. Where the two meet, thin blue glazes tinge the skin, giving the impression of wetness without literal droplets.

Drawing With Contour: The Sculptor’s Hand in Paint

Contours do most of the descriptive work. Broad, elastic lines—often a deep ultramarine bordering on black—loop around shoulder, thigh, and calf, tightening where the form needs emphasis and relaxing where a boundary can fade. This is drawing by pressure, akin to the pressure of a modeling tool in clay. The lines thicken on the near side of the back, then spring forward in a brisk curve around the calf and heel. They are not prison bars; they breathe, split, and sometimes double, as though the artist was feeling for the right edge and leaving his search visible. These contours bring the figure forward from the ambient blue field and give a sense of torsion and weight that pure patches of color would not supply alone.

Brushwork and Surface: Water Made Visible

The surface moves between scumbled veils and more emphatic impasto. In the basin, quick, circular strokes ride over longer dragged ones so that the water seems to rotate gently beneath the figure. Around the right margin, vertical scrapes of pigment thin to reveal the ground, implying a wall washed with light. Across the shoulder, thick, chalky white strokes describe wet highlights, like soap foam or water catching light along the scapula and upper arm. There are visible pentimenti—shifts in outline where earlier decisions remain as ghosts—signs of a searching process rather than a mechanical execution. These traces keep the work alive as an artifact of making, aligning the ritual of washing with the ritual of painting.

Light Without Modeling: Illumination as Temperature and Placement

Illumination here is not built by classical chiaroscuro. Instead, it emerges from the placement of warm and cool shapes and the concentration of pale tones in key areas. The left shoulder and thigh carry the highest lights, pulling the torso forward; the basin’s interior deepens to a denser blue at the lower left, pushing it back. On the right, a cool vertical band suggests light slipping beside a partition, but it is the temperature shift that sells the effect more than any cast shadow. By coordinating color temperatures instead of stacking values, Matisse keeps the surface luminous and avoids heaviness.

The Body as Architecture and Gesture

Matisse treats the body as both architecture and gesture. The architecture shows in the way the torso locks to the pelvis and the legs brace against the basin’s rim—this body has mass and leverage. The gesture shows in the elegant curve that connects neck, back, hip, and thigh—the entire figure is a single continuous line, an arabesque calibrated to the oval below. Because the hands are absorbed into the task and the face is partially obscured, the pose itself becomes the main expressive agent. It is humble, focused, almost devotional, turning a daily hygiene into a classical theme.

The Basin as Halo and Stage

The basin carries symbolic as well as formal weight. Its oval encircles the figure like a halo brought to earth, but it also acts as a stage, elevating the private act to a performance of color and line. The rim’s darker contour reads as a ring that both holds and protects the figure. The way the water’s blue rises up into the body—tinging the feet, climbing the calves, brushing the hip—suggests the reciprocal relationship Matisse prized between figure and ground. The person is not inserted into a space; she is grown from it, as if flesh were a warm variant of the surrounding cools.

Psychological Atmosphere: Solitude Without Melancholy

Despite the dominance of cool tones, the painting does not feel bleak. The blues have oxygen in them; they breathe. The pose communicates concentration, not despair. The cropping removes the social world, but the warm flesh tones and bright hair keep a quiet vitality at the center. This is solitude as restoration—an interlude in which the body returns to itself. The painting’s emotional temperature comes not from facial expression but from the interplay of colors and the rhythm of the pose.

Parallels and Contrasts Within Matisse’s Oeuvre

Placed alongside the explosive “Blue Nude” of the same year, “Nude washing herself” appears more interior and reflective. Both share simplified forms and decisive contours; both explore the authority of blue as a structural color. But where “Blue Nude” spreads the figure across a landscape, here the figure compresses into a sheltered oval. Compared to the 1906–07 patterned interiors, with their carpets and curtains, this canvas suppresses ornament to isolate a single human action. The result is a bridge toward later works in which Matisse would simplify ever further, allowing a few dominant shapes and a handful of colors to carry a scene’s entire expressive burden.

The Modernity of an Everyday Subject

Bathing had a long history in Western art, from antique nymphs to Degas’s modern bathers, but Matisse updates the subject by refusing both the mythological veneer and the observational catalog of incidental detail. There is no tub spigot, no tiled wall, no embroidered towel; the act is modern precisely because it is reduced to essentials. The painting affirms that a contemporary life can be monumental without narrative props, that a quiet domestic gesture can hold the grandeur traditionally reserved for historical or mythic scenes.

Structure and Balance: How the Painting Holds Together

Several counterweights stabilize the composition. The figure leans left, but the dense blue mass to her left anchors that tilt. The strong vertical at the right checks the leftward motion, while the basin’s oval provides a centripetal pull that keeps eye and body from slipping off the canvas. Color helps too: the warm flesh is concentrated centrally; the cold blues intensify toward the periphery, so that the image reads as warm life in a cool world. This arrangement gives the painting poise—a calm equilibrium that makes the moment feel inevitable.

The Role of Negative Space

The “empty” blues are not mere backdrops. Their variety—some glazed, some scumbled, some stained into the ground—establishes a rhythm of breathing spaces around the figure. Passages of near-abstract blue at left, marked by sweeping arcs, echo the curvatures of the body, as if the environment were humming the same melody at a lower register. On the right, a quieter, rectangular block suggests architectural enclosure, a necessary stillness that lets the dynamic lines elsewhere register more vividly.

Process Traces: Drips, Revisions, and the Look of Making

Look closely and you see drips sliding down from the basin’s far edge and from the right-hand boundary. These are not mistakes; they are decisions to leave gravity visible, aligning the subject’s watery action with the liquid nature of paint. The doubled contours around calf and shoulder show that positions were shifted; the artist changed his mind and kept the earlier thought as a memory. Such traces enrich the painting, placing the viewer in the studio, watching seeing become form.

Sensory Translation: How the Painting Feels Wet

The sensation of wetness is achieved by three strategies. First, high-contrast highlights along shoulder and calf simulate slick surfaces catching light. Second, thin, transparent glazes allow underlayers to shimmer like water showing the ground beneath. Third, rhythmic, circular brushstrokes in the basin produce a sense of motion, as if the surface were disturbed by a hand. Without a single droplet painted explicitly, the body appears freshly bathed.

Formal Economy: The Power of Few Elements

The painting’s elegance depends on restraint. A single human figure, one basin, two dominant color families, a couple of structural lines—nothing more is required. This economy keeps attention focused and reveals Matisse’s confidence in the expressive capacity of essentials. The fewer the elements, the clearer their relationships, and the stronger the painting’s internal logic.

Meaning Through Form Rather Than Allegory

There is no overt symbolism, yet the work carries meanings accessed through form. The blue field can read as the world’s cool indifference; the warm body as life’s persistence. The oval can be read as containment, care, or cyclical renewal. The bowed posture suggests humility or introspection. These resonances arise because the forms are simple and archetypal, leaving room for a viewer’s associations without forcing any single reading.

Influence and Legacy: A Quiet Prototype

While not as famous as Matisse’s large bathers or flamboyant interiors, “Nude washing herself” previews key aspects of his later art: the reduction to essential shapes, the reliance on color temperature to describe space, the trust in contour to energize form, the willingness to let process show. It stands as a quiet prototype for Matisse’s belief that painting could be both decorative and profound, that serenity could be built not through detail but through balance and the right pressure of line.

How to Look: A Slow Route Through the Picture

The most rewarding way to view the painting is to enter via the oval basin, then climb the line of the shin to the knee, feel the slight torque of the pelvis, and glide along the back’s curve to the softened head. From there, let the eye drift left through the deeper blues and return along the right-hand vertical, noticing how these cooler planes restore equilibrium. Each circuit of this route makes the image feel more coherent, more inevitable, and the intimacy of the act more dignified.

Conclusion: A Ritual of Color, Water, and Line

“Nude washing herself” turns a simple moment into a distilled experience of modern painting. Blue provides the world, flesh provides life, and contour provides structure. The picture is at once tender and robust: tender in its attention to privacy and touch, robust in its decisive drawing and saturated color. In 1907, as Matisse forged a language that could be both radical and calm, this canvas offered proof that modernity did not require noise. It required clarity, balance, and the courage to let a few elemental forms tell the truth of a living body in space.