Image source: wikiart.org

First Glance: Color Takes Command

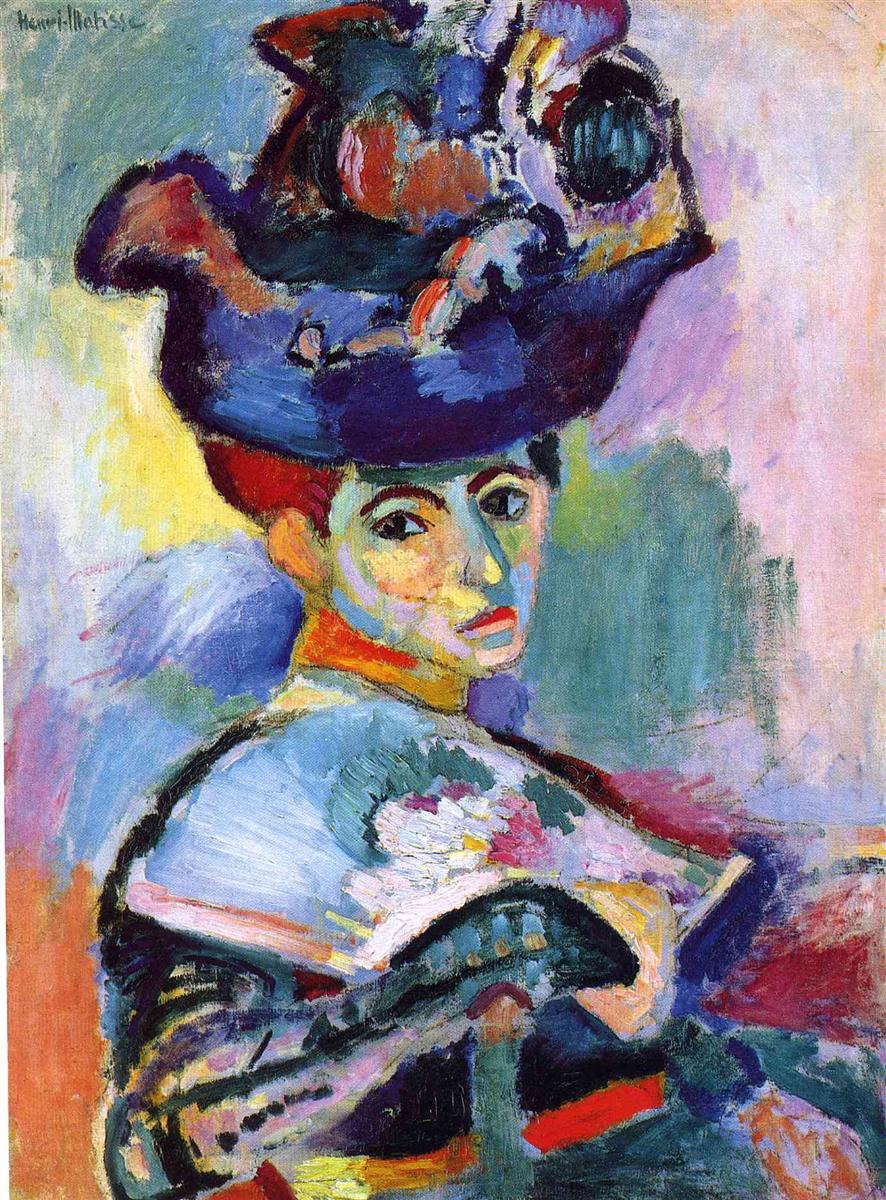

“Woman with a Hat” confronts you with a face built from color rather than shadow. A towering, feathered hat in stormy violets and petrol blues crowns the sitter; her features—cool teal around the eyes, coral along the cheek and mouth, lemon on the ridge of the nose—are assembled like moving pieces of stained glass. The background glows in veils of turquoise, lilac, and rose that never quite settle into a room; they behave like air. At arm’s length you feel the portrait before you parse it: a living person held together by the temperature of pigments and a few decisive darks instead of careful modeling. The brushwork is frank, the palette fearless, and the result unforgettable.

Who She Is and Why This Picture Mattered

The sitter is Amélie Matisse, the artist’s wife and frequent model. The painting appeared at the 1905 Salon d’Automne in Paris, in the same gallery where André Derain, Maurice de Vlaminck, and others were showing incandescent landscapes. A critic, jolted by the high-key palettes, famously called the room a cage of “wild beasts” (les fauves). This portrait stood at the center of that charge. Likeness was present, but the means—emeralds, violets, citrus yellows—felt shocking. The canvas was purchased by Leo and Gertrude Stein, an early endorsement that helped to fix it as a landmark. More than a century later, its audacity still reads as fresh intention rather than gimmick.

Composition: A Triangle of Hat, Face, and Fan

Matisse sets up a clear triangular arrangement. At the apex is the hat, a sculptural mass whose silhouette nearly touches the top edge. The base is formed by Amélie’s shoulders and the fan or book she holds, an oblique shape that tilts the lower half of the canvas. The face sits between, slightly turned, gaze steady. The triangle stabilizes a very active surface: large, directional strokes in the hat, wider, level passages in the background, and shorter, chiseled marks in the face. Because the pose turns to the left while the fan tips to the right, the figure feels poised rather than frozen—an elegant pivot captured mid-thought.

Color Architecture: Warm–Cool Chords Doing the Drawing

The portrait is constructed from complementary pairs. Red and green meet at almost every boundary (coral cheek against teal eye socket; orange collar against sea-green ground), and blue–orange and violet–yellow play supporting roles. These pairs are not mere decoration. They create edges and volume without charcoal or brown shadow. The cheek’s coral meets a thin seam of cool blue to announce the turn of the face; a mustard note on the nose’s bridge becomes highlight and structure at once; the mouth’s rose floats in a zone of cooler blue to make it advance. The hat’s violets push against lemon and mint flashes so it reads as plush material rather than a dark void. Because pigments stay clean and largely unblended, the portrait keeps a luminous inner light.

The Role of Black and “Drawing with Darks”

Black appears sparingly—in the contour that skims the shoulder, the arc of the eyebrows, small notes around the fan, and deep accents inside the hat. These are not shadows; they are armatures. Like the lead in stained glass, the darks brace bright panes and prevent the high key from drifting. They also organize tempo: a thicker black at the shoulder slows the eye, finer darks around the features quicken it. Remove those marks in your imagination and the portrait softens, even wobbles; restore them and its architecture locks.

Brushwork and the Record of Decisions

The surface remains wonderfully legible. Paint is laid in confident, visible swipes that align with the form they describe: horizontal lanes in the background, curved sweeps across the hat, short planes stepping down the cheek and jaw. In several places Matisse leaves the primed ground to breathe between strokes. Those reserves become literal light; they keep mixtures clean and replicate glare more convincingly than a loaded highlight would. The painting therefore owns its making: you don’t just see the sitter—you see the thinking that built her.

Light Without Chiaroscuro

Rather than a single spotlight, “Woman with a Hat” conveys a climate. Strong ambient light from multiple directions seems to bathe the sitter: cool illumination from the left (teal and blue), warm reflections from the right (rose and orange). The famous green down the nose—echoed more emphatically in “The Green Line” later that year—is not an arbitrary flourish; it abbreviates the shadow of the bridge while also separating the two temperature zones. Highlights are shifts in value within a color family (pale turquoise beside deeper teal), which makes the face feel lit from within instead of glazed from without.

Clothing, Fan, and the Theater of Ornament

Amélie’s costume, a fashionable confection of the day, becomes a field where Matisse tests big color relations. The bodice is a cool world of blues and greens that set off the warmth in the skin. A burst of white floral paint—laid thick, almost impasto—acts as a focal accent and a tactile contrast to the smoother planes around it. The fan or book serves as a counterweight: its darker, earthier notes anchor the portrait and echo the black structure on the shoulder. Ornament here is not a digression from identity; it is part of it. Matisse believed pattern could carry meaning, and the sitter’s taste becomes visible as a rhythm of color patches.

Psychology Delivered Through Structure

There is no theatrical expression—no grin, no frown—yet the portrait feels psychologically complete. The eyes, framed by assertive brows and cool sockets, read as calm and appraising. The slight set of the mouth, more line than lip, suggests resolve. These signals ride on top of deeper structural cues: the firm vertical of the nose, the hat’s grand mass, the stabilizing triangle of pose. The effect is poise rather than prettiness. Even critics shocked in 1905 acknowledged the sovereignty of Amélie’s presence. She looks back, not out.

Fauvism’s Break with Naturalism—And Its Discipline

Color here is liberated from local truth (skin is not “flesh-colored”), but it is not random. The discipline is optical and structural: complements placed to make volume, temperature used to build depth, darks deployed to hold a composition that might otherwise fragment. The portrait demonstrates that Fauvism is not merely “wild color.” It is a system where color replaces modeling as the engine of form. That is why the canvas remains persuasive long after shock value fades.

Relation to Precedents and to Matisse’s Own Work

The picture converses with multiple traditions. From Manet and the Impressionists Matisse inherits the belief that modern life—here, a woman in contemporary fashion—is a worthy subject. From Gauguin and the Nabis he borrows courage for non-natural color and a taste for flattened, decorative space. From Cézanne he adapts the idea that form can be constructed by adjacent planes rather than blended tones. Within Matisse’s own trajectory, this portrait sits alongside “The Green Line” as a two-part manifesto: one leverages a frontal architecture; the other compresses the same idea into a slashing vertical. Later interiors, “Harmony in Red,” and the paper cut-outs all trace their logic—color as structure—back to these 1905 discoveries.

Background as Active Space

The background refuses to be a neutral wall. It is a shallow, breathing field of cool hues—sea-green, mint, lilac—laid in wide, directional strokes. Its job is twofold. First, it provides the cool counterweight that makes warmer facial notes advance. Second, it keeps the picture shallow and decorative rather than theatrical. Because the brushwork remains visible and the hues are clean, the figure sits in a zone of air rather than an illusionistic room. That is exactly where Fauvist color thrives.

Materiality and Scale

At intimate scale, the canvas rewards close inspection. Thick strokes on the hat catch real light; thinner drags around the face let the weave peek through. The material differences cue nearness and texture: you almost feel felt and feather up top, smooth skin and silk below. These physical facts help the portrait avoid the flatness that sometimes dogs high-key color. The surface is a terrain; your eye hikes it.

The Hat: A Painterly Mountain

The hat is the portrait’s weather system. Its violets, petrol blues, and inky accents create a cool dome that stabilizes the warm lower half. Formally it is a counter-mass that keeps the head from floating in a vapor of pastel ground. Psychologically it signals presence and style. Matisse paints it not as a catalog object but as a moving arrangement of color planes. Feathers and ribbons dissolve into brushwork; we register “hat” through silhouette and temperature rather than descriptive detail. That choice allows the head beneath to command attention.

Rhythm and the Viewer’s Path

The painting offers a clear path for the eye. Begin on the hat’s dark brim, drop to the eyes (the sharpest contrasts in the face), slide down the green nose ridge to the coral mouth, and sweep across the white floral accent to the anchoring darks of the fan. Loop upward along the shoulder’s black seam and return to the hat. This circuit repeats easily because each section previews the next with echoes of hue and direction. Looking becomes a musical phrase rather than an act of scrutiny.

How to Read the Color Choices

If the palette seems outrageous at first, test it piece by piece. The cool zones of the cheek and temple are not random—they read as the side turned to ambient blue light. The warm coral around the mouth and jaw feels like light bouncing from the garment. The green along the nose gathers both ideas into a single structural sign. Seen this way, the colors are not against nature; they are a concentrated translation of how strong light scrambles local color into temperature.

Why the Portrait Still Feels New

Contemporary viewers are surrounded by color, yet very little of it carries structure. This painting does. It shows that a handful of well-placed hues can hold likeness, space, mood, and texture without the props of academic shadow. The result is both economical and generous: you sense complexity, but you can also count the decisions. That transparency keeps the work modern. It trusts us to participate in its making.

Influence and Afterlife

“Woman with a Hat” helped unlock the twentieth century’s belief in color as a primary vehicle of meaning—from the sleek geometry of Color Field painting to the saturated portraits of modern photography and design. Within Matisse’s oeuvre, it lights the path to the interiors of the Nice period, where fabrics and shutters are orchestrated like this hat and face; to “The Red Studio,” where color becomes architecture; and to the cut-outs, where hue and edge become one.

Conclusion: A Likeness Reinvented

“Woman with a Hat” stands as proof that likeness is more than resemblance. Built from warm–cool chords, steadied by a few dark accents, and delivered with visible, confident touch, it captures presence, temperament, and style without leaning on conventional modeling. What shocked in 1905 now reads as clarity. Matisse does not drape novelty over a portrait; he rebuilds portraiture from the ground up, with color doing the heavy lifting and the human gaze tying everything together.