Image source: wikiart.org

First Look: A Bacchic Gesture in a Field of Light

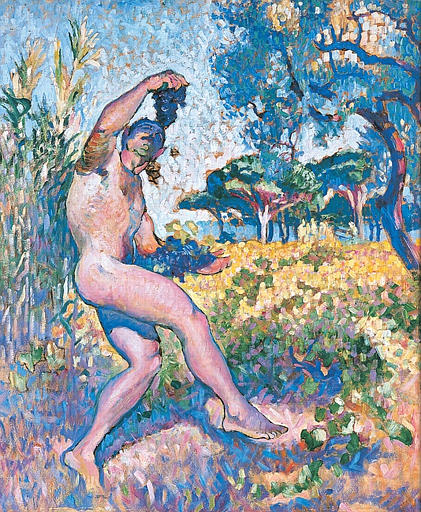

“Study for Wildlife, The Man with the Cluster” dates to 1905, the incandescent season when Henri Matisse transformed the grammar of modern painting. A nude male figure steps lightly across a sunlit field, one arm flung high to display a heavy cluster of grapes. His body is ringed with cool blues and violets, his shadows bloom with lilac, and the air around him ripples in small, distinct strokes of yellow, green, and blue. The landscape behind him opens into a line of Mediterranean pines under a sky streaked with warm clouds. The scene is both classical and startlingly new: a bacchic reveler summoned not with academic modeling but with color and touch that turn light into palpable substance.

The 1905 Breakthrough and Its Relevance Here

This study belongs to the short arc that runs from Matisse’s late Neo-Impressionist experiments to the explosive Fauvist canvases shown at the 1905 Salon d’Automne. It keeps the divisionist memory—small, separate touches that allow light to circulate—while discarding rigid pointillist regularity. In its place Matisse introduces larger mosaic strokes, simplified planes, and the bold use of complementary color to build form. The painting reads as a field note from that transition: a figure conceived with the freedom of Fauvism and sustained by the flicker of divisionist light.

Composition as Dance

The figure forms a dynamic diagonal from raised hand to grounded heel. The lifted left foot, bent knee, and tilted torso describe a spiral that animates the whole surface. Matisse counterbalances this human curve with a gentle, lateral rhythm of trees and horizon. The tall stalks at left echo the vertical of the figure’s shin; the pines across the middle distance answer his raised arm with slimmer uprights. These correspondences prevent the figure from feeling pasted onto the landscape; they fold him into its cadences so the entire canvas moves like a single phrase.

A Classical Motif Reimagined

Grapes, a nude male, and a dancing step evoke Bacchus and the pastoral feasts of antiquity. Matisse keeps the symbolism but sheds the studio’s brown shadows and polished surfaces. Instead, the body is defined by temperature—cool violets and blues meeting warm rose and apricot—so that classical ease becomes a modern sensation. The painting proposes a new Arcadia where myth is less a story than a mood produced by color and air.

Color Architecture and the Logic of Complements

The landscape is constructed from complementary chords. Yellows brighten the field and, by contrast, push the figure’s blue-violet contours into crisp relief. Greens sit against touches of red and orange in the trees and sky, creating the shimmer of Mediterranean afternoon. The grapes themselves oscillate between deep blue and wine-purple, harmonizing with the figure’s blue shadow and giving the gesture a chromatic inevitability. These complements are laid side by side rather than blended, so boundaries are events—moments when warm and cool meet and a form turns in space without resorting to heavy outline.

Divisionist Memory, Fauvist Courage

The surface is a weave of distinct strokes, but they vary in size and pressure. In the grass Matisse uses short dashes that jostle like seed heads in wind. Along the torso the strokes lengthen to follow muscle and bone, creating volume with direction rather than with tone. In the sky the marks flatten and spread to make thin veils of color that read as air. This fluent variation—tight here, loose there—demonstrates how far he had moved from pointillist dogma while preserving its greatest insight: that light lives in the intervals between touches.

Drawing With Color Edges

Look closely at the torso and you will find almost no enclosing line. The contour is made by the juxtaposition of lilac flesh and turquoise shadow, by a sliver of cool blue against a warmer apricot. Even the hand that clasps the grapes is built from small wedges of cool and warm laid at angles that imply knuckles and palm. Where Matisse does use a darker accent—around the eye, under the jaw—it functions like a brace that tightens the brilliant palette rather than like a traditional shadow.

Light, Hour, and the Meteorology of Hue

Shadows are not brown; they are violet and blue, a choice truer to the color of form in blazing sun. Highlights are not white; they are lifted versions of the surrounding hue—pale rose on the shoulder, lemon on the thigh, powder blue on the calf. This chromatic weather announces a high, dry hour when forms compress into planes and reflected color floods surfaces. The grapes glitter not through dots of white but through small jumps of value within the same cool family.

The Figure’s Psychology Carried by Gesture

The man’s head tips toward his prize, eyes narrowed not in strain but in appraisal. The raised arm, flexed wrist, and lifted knee convey a celebratory showman’s poise. Yet the body is relaxed and lyrical, closer to dance than to labor. Matisse avoids caricature; he lets the body’s open spiral, the grapes’ pendulum weight, and the surrounding field’s vibration describe a mood of plenitude without literal narrative.

Landscape as Partner, Not Backdrop

The grove of pines, the bright meadow, and the river of sky participate in the action. Their rhythms answer the figure’s arcs; their colors feed into his temperature. Yellow grass climbs into the leg as reflected light; blue from the sky cools the flank and calf; green from the trees slips into the shadows. The landscape is not a stage set but a reservoir of color that infiltrates flesh, an exchange that deepens the feeling of belonging the pastoral traditionally promises.

The Role of Reserve and the Living Ground

Between many strokes small glints of primed canvas remain. These reserves behave as real light: they keep mixtures clean, prevent the high key from going chalky, and reproduce the sparkle of heat rising from ground. Along the outer arm and hip, flashes of ground read as glare. Matisse lets the white of the support do part of the work, which makes the palette more transparent and the light more convincing.

Material Presence and the Tactility of Paint

In passages of the trunk and thigh the paint is laid thick enough to create ridges; in the meadow the touch is lighter, revealing the weave. This varied topography allows the canvas to catch actual light differently across its surface, so that the body feels warm and solid and the field feels airy and mobile. Material behavior becomes a proxy for climate: heavy strokes equal heat and nearness, thin scumbles equal distance and glare.

Anticipations of “The Joy of Life”

Many elements here foreshadow Matisse’s great pastoral of 1905–06, “The Joy of Life.” The dancing arc of the figure, the chromatic shadows, the Mediterranean grove, and the fusion of decoration with landscape all point forward. This study suggests a rehearsal of one actor in that larger drama: a celebrant whose gesture sets the key for a world tuned to ease and abundance. The substitution of temperature for tone—violet shadow for brown, blue contour for gray—will become the operating principle of that symphonic canvas.

Kinship with “Luxe, Calme et Volupté”

There is also a backward glance to “Luxe, Calme et Volupté” of 1904, where Matisse applied pointillist technique to an Arcadian scene. Compared with the earlier picture’s meticulous dots, this study is freer, its strokes larger and more directional, its color more saturated. It shows Matisse retaining what he needed from Seurat’s legacy—the vibration of adjacent notes—while discarding what slowed him—the mechanical regularity. The result is a more bodily, musical surface.

Space Without Linear Perspective

Depth is achieved by overlap, scale, and temperature, not by a plotted system of vanishing points. The figure overlaps the meadow; the meadow overlaps the tree line; the trees overlap the sky. Cooler, less saturated color recedes; warmer, cleaner notes advance. The ground slides under the raised foot without a single cast shadow rendered in gray. The painting stays shallow enough to be decorative and deep enough to be inhabitable.

Rhythm, Tempo, and the Viewer’s Path

The composition organizes a graceful route for the eye. Begin at the grapes, dark against the pale sky. Drop along the arm’s lilac to the chest’s warm plane. Spiral around the torso via the blue contour, step across the lifted knee into the dazzle of the field, and then drift along the tree line to the cool distance. Return through the tall grasses at left and rise again to the cluster—a loop that repeats effortlessly. That looping rhythm is the pastoral mood translated into looking.

The Body as a Landscape of Hues

Matisse treats the figure like terrain. Calf and thigh are blue hills that round into apricot sunlight; abdomen and chest are linked plateaus; clavicle and shoulder blade glint like ridgelines under a high sun. This metaphor is not rhetorical; it is how the color works. The same vocabulary that constructs pines and meadow constructs wrist and ankle. Person and place share a single chromatic DNA, which is why the figure feels native to the field.

Decorative Intelligence Without Losing Nature

Arabesque branches, scalloped edges of foliage, and the figure’s serpentine silhouette evoke decorative art—textiles, tiles, carved wood—that Matisse revered. Yet nothing becomes merely ornament. The decorative turn clarifies structure, distributing accents so the eye never stalls. Pattern and nature are not opposites here; pattern is the means by which nature’s rhythms become visible.

Why the Painting Still Feels New

More than a century later, the study remains fresh because it relocates accuracy from detail to effect. It acknowledges that in hard sunlight and moving air we perceive planes and temperatures before we perceive anatomical micro-facts. It proves that a body can be solid and alive when modeled with chromatic complements rather than with brown shadow. It also keeps process visible—strokes remain strokes—so that the viewer can reconstruct the act of seeing.

How to Look So the Picture Opens

Let your gaze rest on the green-blue edge of the back and notice how it cools the warm interior of the torso. Watch the grapes alternate between blue and violet and see how those notes reappear in the figure’s cast shadow and in distant trees. Compare the short, choppy strokes in the meadow with the longer, skin-following strokes on the thigh. Step back and feel the diagonal from hand to heel that organizes the whole; step close and appreciate the small gaps of canvas that act as sparks of light. After a few circuits the scene becomes not a man in a field but a single system of energies.

Context in the Collioure Cycle

Within the 1905 Collioure works, this study occupies a special place. The seascapes push toward large planes; the interiors explore color as architecture; the olive groves tesselate into shimmering nets. This canvas synthesizes those lines: a figure with the clarity of an interior, a field with the flicker of a grove, a sky with the broad planes of the sea. It demonstrates that the vocabulary Matisse honed that summer could serve not only houses and harbors but also classical human subjects.

A Note on Scale and Presence

The scale—intimate yet generous—allows brushwork to remain legible while granting the figure full stature. You can read each decision and still feel the breadth of a step and the lift of an arm. That balance between intimacy and amplitude typifies Matisse’s finest 1905 studies and explains their continuing appeal in reproduction and in the gallery.

Conclusion: A Study That Contains a World

“Study for Wildlife, The Man with the Cluster” offers more than preparation; it contains the essence of a new order. A single dancer, a handful of trees, a field of sunshine, and the logic of complementary color together generate an Arcadia rooted in the present tense. The figure is classical, the method modern, and the feeling timeless. In this small, radiant canvas Matisse demonstrates how a body can be built from temperature, how space can be woven from strokes, and how joy can be made visible without narrative. The grapes lifted to the sky are more than fruit; they are the painter’s toast to color’s power to carry life.