Image source: wikiart.org

First Impressions: An Arcadia Built from Color

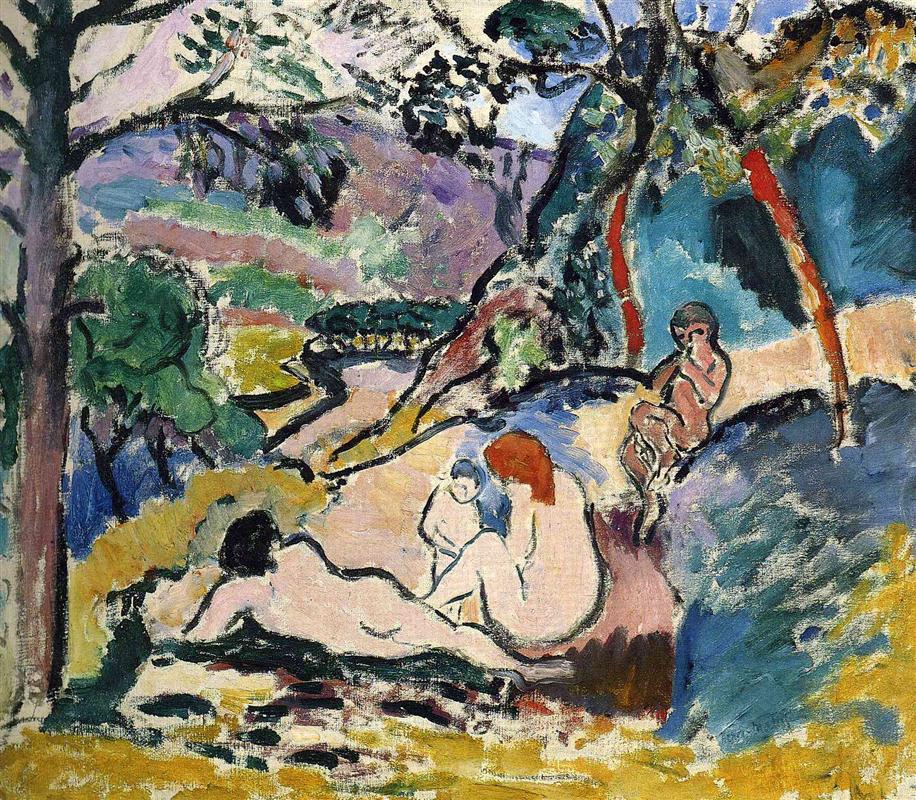

Henri Matisse’s “Pastoral” (1905) stages a timeless Arcadian scene with the tools of a brand-new language. A cluster of nude figures reclines and converses on a sloping bank beneath wind-tossed trees. Hills ripple into the distance; a stream or path curls through a valley; leaves and sky trade places in a mosaic of brushstrokes. Nothing is modeled the old way. Instead, saturated patches of violet, turquoise, citron, and rose, pinned by decisive black contours, carry light, space, and emotion. The title promises pastoral ease; the execution delivers a modern shock. In one compact canvas Matisse asks an old subject—humans at peace with nature—to host a radical method in which color thinks, line conducts, and reserve of canvas becomes literal light.

Collioure, 1905: The Crucible of Fauvism

Painted during the incandescent Collioure summer, “Pastoral” stands at the hinge between Neo-Impressionism’s discipline and the full cry of Fauvism. Only a year earlier Matisse had tested pointillist procedures in “Luxe, Calme et Volupté,” a shimmering, Seurat-inflected Arcadia. By 1905 he had shed the tiny dots for larger, sculptural strokes and simplified planes. Working shoulder to shoulder with André Derain, he discovered that complementary chords—orange against blue, red against green, yellow against violet—could erect forms as surely as contour lines. “Pastoral” brings that discovery to the human figure, the most risk-laden subject of all. It proves that bodies can be articulated by temperature and rhythm rather than by shaded anatomy.

Composition as Flow and Counterflow

The design is anchored by two long diagonals. A broad, pale path or stream sweeps from the upper right down toward the center, cutting an S-curve that invites the eye to wander. It is countered by a dark, tree-topped ridge that climbs from left to center, then slips behind the bank where the figures rest. Trunks and branches arc across the top like a canopy; the largest trunk rises on the far left, its vertical mass framing the scene like a stage post. These forces create a shallow amphitheater in which the nudes appear both sheltered and connected to distance. The reclining figure at lower left establishes a horizontal base; two seated companions turn inward in a compact triangle; and a small, perched figure on the right acts as a visual hinge between foreground intimacy and the landscape’s outward drift. The composition feels improvised and inevitable at once, as if the terrain itself had decided where conversation should happen.

Color as Structure and Weather

Every major form is built from color, not shading. The hillside where the figures recline is a lilac-rose plate edged by deep green and midnight blue. The distant ground alternates in broad, horizontal belts of lavender, mint, and blue-gray, so space reads as temperature zones rather than as a plotted perspective grid. Dark emeralds and bottle greens describe foliage; sudden flares of cadmium red in tree trunks are not “realistic” bark but hot accents that keep the cooler field alive. Matisse does not enforce a single local color for any object. Sky infiltrates leaf, and leaf returns the favor, because that is how bright light actually behaves. The result is meteorological truth without literal cloud and shadow. The air feels stirred yet clean, a weather made of pigments.

The Productive Use of Black

Black is sparing and sovereign. It rims the contours of the nudes, slashes through tree limbs, and punctuates the valley’s winding line. These blacks do not cast shadow; they act like the lead of stained glass—armatures that lock brilliant panes into one organism. They also keep the palette from floating. In a world of high-key color, a few decisive darks provide weight and tempo. Where the reclining figure meets the bank, black curves establish the shoulder, hip, and thigh with the economy of calligraphy. The same black braces the treetop canopy, its zigzags turning scattered leaves into a single overarching rhythm.

Brushwork, Impasto, and the Record of Seeing

The surface is a tapestry of varied touches. Thick, creamy arcs build the curve of the bank; dry, scumbled notes drag across underlayers, leaving the primed fabric to glitter like dust-bright air; short, square strokes mass into tree crowns; longer, directional sweeps push the eye along the valley path. Matisse lets each mark keep its identity. The canvas reads like an edited diary of decisions rather than a polished illusion. That frankness makes the landscape tactile: ridges in the green catch real light; scraped passages feel like stone; thin blue washes have the liquidity of shade. The painting’s weather is partly the day’s and partly paint’s.

Figures Made from Temperature and Line

The nudes refuse academic modeling. The prone figure at lower left is a pale, warm swath bounded by black and cooled in recesses by mint and blue; the body’s weight is felt where warm plane meets dark edge. The central pair—one auburn-haired, one capped in cool blue—are stacked volumes defined by the encounter of lilac, peach, and teal. The perched figure on the right is drawn with even greater economy: a sienna-orange plane bounded by a fine black edge, knees folded, hand to face. Matisse’s reliance on color contrast in place of shadow means these bodies glow with the same clarity as the landscape. People and place share a single visual grammar, which is precisely the pastoral ideal translated into paint.

A Modern Take on the Pastoral Tradition

From Giorgione to Titian to Poussin, pastoral scenes have promised an escape from the city into a realm where bodies and earth coexist without strain. Matisse keeps the promise and revises its terms. Classical pastels and golden browns give way to violets and turquoises; carefully modeled forms yield to arabesque and plane; allegory softens into simple leisure. The figures do nothing momentous—no pipes, no dancing shepherds—because their mere presence in this chromatic grove is enough. The title’s music is in the color. Where earlier Arcadias coaxed serenity from harmony of tone, Matisse finds it in daring complements that somehow rest the eye rather than jar it. The pastoral is no longer a stage for myth; it becomes a test site where pure color proves it can carry human subject matter with dignity and ease.

Space Without Linear Perspective

Depth in “Pastoral” arises from overlaps, scale shifts, and the stacking of temperature belts, not from converging orthogonals. The near bank overlaps the mid-slope; the mid-slope overlaps the distant ridge; small trees recede by becoming cooler and shorter. A sinuous path narrows as it approaches a dark clump of trees, which reads convincingly as distance even though no vanishing point is asserted. Because Matisse refuses the old grid, the picture plane remains active. You are never invited to fall through the surface; you are asked to travel across it. That gentle refusal of window-like space keeps the figures firmly planted in the same decorative world as their surroundings, which is essential to the painting’s calm.

The Role of Reserve and the White Ground

Between nearly every stroke a breath of primed canvas shows through, especially in the sky, central bank, and distant slopes. These reserves of ground are not sloppiness; they are literal light. They keep mixtures clean, admit air between hot and cool patches, and create a vibration that mimics glare. In the central nude’s back and hip, flecks of ground serve as highlights more persuasively than any glazed white could. Along the horizon, unpainted seams read as haze. The painting shines from within because Matisse allows the canvas to collaborate.

Rhythm and the Viewer’s Path

“Pastoral” offers a route for the eye. Begin at the left trunk and step down into the warm foreground, where dark green shapes pool like shadow. Move to the reclining figure and follow the curve of the bank around to the seated pair. Climb the pale path to the perched figure at right, then drift into the valley’s purple bands and back up to the canopy. This loop—ground to figure to distance to canopy—repeats with each glance, and the picture’s restfulness comes from the ease of that cycle. The eye is never trapped; nor is it expelled. It circulates like air through trees.

Dialogues with Cézanne, Gauguin, and Matisse Himself

The picture acknowledges Cézanne’s bathers—the stacked planes, the figures nested in landscape—and Gauguin’s cloisonné contours and audacious local color. Yet Matisse refuses the anxiety that can haunt both predecessors. His line curves rather than carves; his complements spark without bruising. The painting also converses with his own earlier and later works. It carries forward the motif of Arcadian leisure from “Luxe, Calme et Volupté” while replacing optical dots with confident planes. It foreshadows the large, orchestral “Bonheur de Vivre” of 1905–06, where nudes and grove bloom into a complete decorative cosmos. “Pastoral” feels like a chamber piece that contains the DNA of a symphony.

Gesture, Gender, and the Psychology of Ease

The nudes’ gestures matter precisely because they are so unforced. The recliner faces away, which protects the scene from voyeurism and lets the viewer share her outlook rather than her body. The central pair fold toward each other in quiet talk; the red hair and blue cap are emotional temperatures rather than identifying traits. The perched figure—perhaps younger—holds a hand to the face, caught between rest and readiness. There is no narrative beyond being at ease. That absence is a choice: Matisse wants the viewer to feel the quality of time rather than the content of events. The psychology lies in the palette. Warm banks foster intimacy; cool distance invites free breathing; black accents provide calm structure.

Trees as Calligraphy and Architecture

Trees bear a double responsibility. They provide a vertical architecture that frames the figures, and they write the painting’s calligraphy across the top. The left trunk is a sober column; the right trunk, banded with red, is both support and flame. Branches scratch through sky in broken blacks and blues, tying distant hills to near leaves. In several places foliage resolves into abutting color tiles—olive against teal, mustard against violet—so that leaf becomes pure relation. The canopy reads not as a naturalistic portrait of species but as a score of marks that modulate the light below.

Materiality and the Sense of Place

Much of the Mediterranean enters the canvas through material facts. Thick greens catch real light like sun on waxy leaves; scumbled lilacs recall glare on chalky paths; blue-black seams suggest deep shade without turning the scene somber. Even the roughness where two strokes fail to meet feels like heat. The place is not recorded by detail—no specific flora, no named mountain—but through the way paint behaves. The viewer’s memory of hot stone, cool pockets of undergrowth, and distant humidity is called up by the tactility of pigment.

Why “Pastoral” Still Feels New

The painting retains its freshness because it relocates accuracy from detail to effect. Anatomy is abbreviated, yet bodies feel present and weighted. The valley is a set of colored belts, yet distance breathes. Leaves are marks, yet shade collects and cools. The truth of the scene resides not in catalogued facts but in relations—warm next to cool, dark bracing light, thick against thin. Contemporary eyes, used to cameras and screens, recognize in this method a kind of honesty: a clear statement of what looking actually feels like when light is strong and air is moving.

How to Look so the Picture Opens

Let the eye ride the pale path from the right edge into the center, noticing how its temperature shifts—cool where it meets blue shadow, warmer where it crosses pink ground. Pause on the central nudes and pay attention to the seams where peach meets mint and black. Walk along the dark ridge to the left and down the trunk, then climb back through the canopy, where sky shows through in lilac intervals. Each circuit clarifies how the painting works: edges are events between colors; space is a stack of temperatures; time is a rhythm of return. After a few loops the canvas no longer looks “broken up”; it looks alive.

The Pastoral Reimagined as a Modern Promise

At heart “Pastoral” offers a proposition: the ancient ideal of ease can survive in a modern world if painting learns to speak plainly in color. Matisse banishes anecdote, dresses serenity in unexpected hues, and trusts the viewer to accept bodies as music rather than as textbooks. The result is not a retreat from modernity but a manifesto for a new kind of clarity—one in which the simplest relations of hue and line deliver the fullness of a day outdoors with friends. The grove is timeless; the language is new; the promise still persuades.

Conclusion: A Lyrical Grove Where Color Speaks First

“Pastoral” builds a complete world from a handful of decisions. A sloping bank becomes a stage; black lines brace a canopy; belts of violet and green discover depth; three nudes and a perched companion breathe the same air as trees and hills. With these elements Matisse composes a scene that is at once classical in spirit and modern in facture. The painting is small in scale and large in consequence. It demonstrates that color can carry meaning without props, that leisure can be profound without allegory, and that painting, at its most direct, can still invent Arcadia.