Image source: wikiart.org

1905 In Collioure And The Moment When Color Took Command

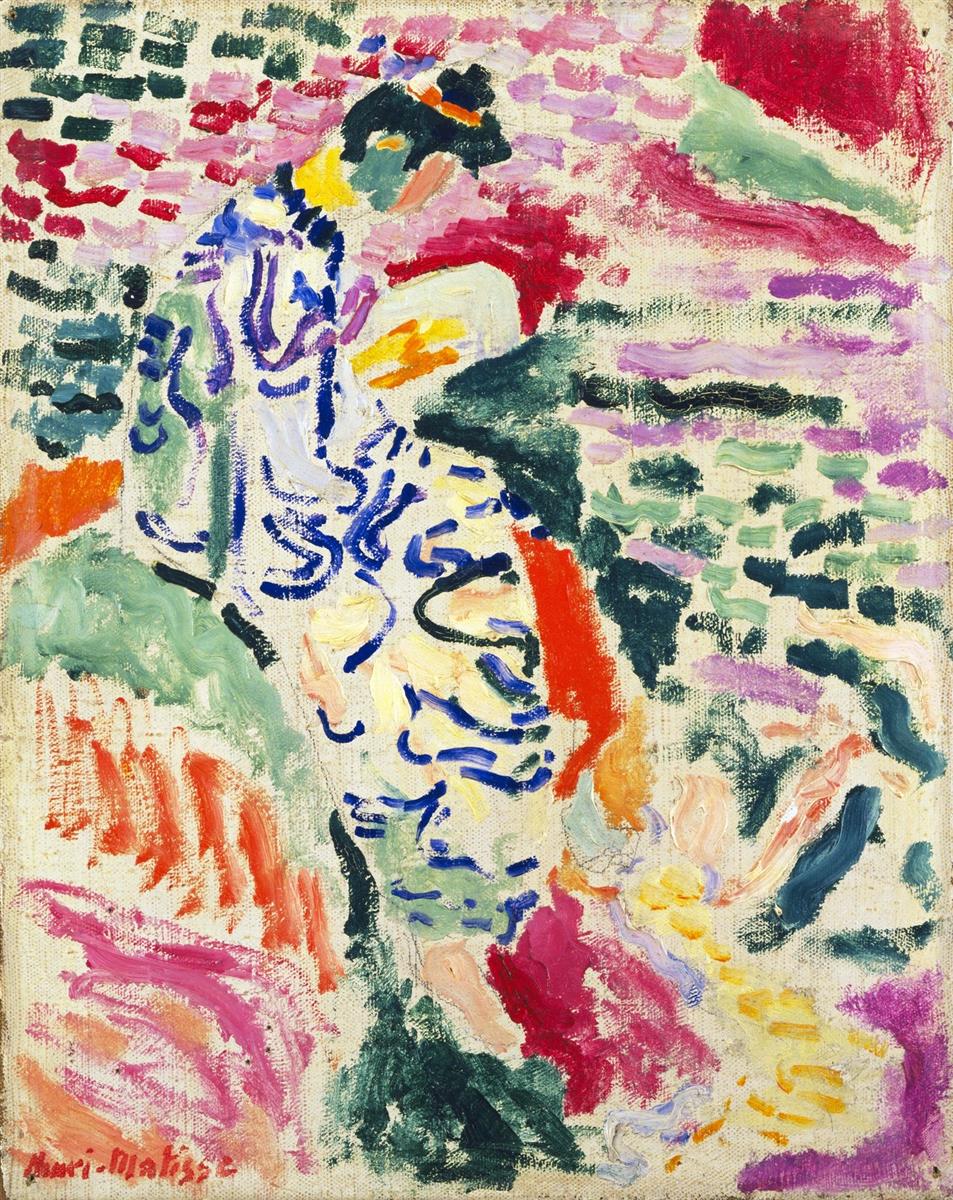

“Woman Beside the Water” was painted in 1905, the incandescent summer when Henri Matisse found a language of pure color that would soon be labeled Fauvism. Working on the Mediterranean coast, he abandoned careful tonal modeling and the cool science of divisionism for something faster, freer, and more candid about sensation. The canvas belongs to that breakthrough: it turns an intimate figure at the water’s edge into a stage where light, temperature, and touch set the rules. Instead of chasing likeness, Matisse constructs feeling, letting chords of rose, lilac, mint, viridian, ultramarine, and a startling vermilion become the architecture of the scene.

Subject And First Impressions

At the center a woman bends slightly forward, her head lowered as if watching ripples or turning inward in thought. She wears a patterned robe whose creamy ground is quickened by cobalt blue arabesques. Around her the world is broken into dabs: pinks and violets above that read as air and reflected light; green-black strokes to the right that thicken into water; coral, orange, and magenta notes below that behave like shoreline and earth. The canvas is small but it feels large because the strokes are decisive and the reserves of bare linen allow light to flood the surface. One senses not a portrait session but a moment caught between breaths.

Composition And The Poise Of The Figure

The composition is a tall rectangle that tips gently from upper left to lower right. The woman’s body, a light vertical with blue patterns, is set just off center; a fierce red-orange bar beside her operates like a counterweight, keeping the figure from melting into the background while also implying a sash, towel, or sunlit edge of ground. The darker, horizontal mass at right suggests the water’s plane; the curved, rose-lilac passages below pull the eye diagonally upward along the shoreline. This choreography leads the gaze in a loop—down the robe, across the red accent, into the water, back through the pinks to the face—so that looking becomes a slow, circular stroll.

Color As Structure And Emotional Register

Color is the true skeleton here. The robe’s blue motifs animate the creamy field the way calligraphy animates paper. Cool greens lay down the water; near-black accents deepen it; pale violet and pink tiles state the flicker of light and wind. The vermilion vertical behaves like heat itself, striking the composition with a shock that lifts everything around it to higher intensity. Complementary pairs create the pulse: blue plays against orange, red against green, purple against yellow. The woman does not sit in a neutral world; she is absorbed by an atmosphere of temperature contrasts, and those contrasts communicate mood—an alert, sun-warmed quiet.

The Productive Power Of The White Ground

Matisse leaves generous reserves of primed canvas visible between strokes. These bright interstices are not emptiness; they are active light. They keep the palette clean, prevent muddy blends, and give the whole surface the airy glare of Mediterranean noon. Around the woman’s robe, the ground flickers like reflected sun; across the skylike upper band, the untouched linen becomes the day’s brightness. The picture therefore shines from within rather than relying on heavy highlights painted over the top.

Brushwork, Tempo, And Material Presence

The paint is handled in short, confident dabs and lifted strokes that remember divisionism without submitting to its rigid grammar. In the water, darker touches stack like little waves. In the robe, the blue marks sway with the body’s curve, turning decoration into rhythm. In the foreground, thicker coral and magenta strokes read as hot ground. Matisse varies pressure and speed so the surface pulses: some marks land like notes struck on a piano; others smear like a violin’s bow. The material fact of oil—its slipperiness, its drag, its capacity for both opacity and translucency—becomes a surrogate for sensation.

Drawing With Color Instead Of Contour

Contours are scarce. A slight black line near the robe and a darker arc under the head state pivotal edges, but most “drawing” happens where one field of color meets another. The left cheek emerges from the opposition between warm flesh notes and the cool greens around it. The arm is sensed because its creamy strokes interrupt the darker mass beside them. This method allows Matisse to keep the figure integrated with its setting; woman and water share a single syntax of marks.

Water Rendered As Rhythm

Rather than paint literal ripples, Matisse builds the water from compact, horizontally leaning dabs of green, teal, and green-black. They thicken near the center, thin toward the edges, and occasionally flip direction, implying little eddies. A lavender bar slides through them like a sliver of reflected sky. The water is not a mirror; it is a tempo. Its rhythm is answered by the robe’s patterned beats and the pink tesserae of light above, so the entire canvas behaves like a small orchestra kept to a tight, lively meter.

Clothing, Pattern, And Cross-Cultural Resonances

The robe’s sinuous cobalt flourishes carry echoes of East Asian textiles and of the Japonisme that swept Paris in the decades before 1905. Matisse admired such decorative arts for their flattening of space and their embrace of arabesque. Here, the pattern does double duty. It proclaims the modern taste for the decorative and, more importantly, supplies a musical line that structures the figure. Where an academic painter might have modeled folds with shadow, Matisse replaces depth with design, letting the robe’s blue calligraphy tell us how the body turns.

Light, Atmosphere, And Time Of Day

The palette suggests searing daylight diffused by a breeze. Shadows are not gray; they are violet and green. The flesh is not brown; it is a collage of warm peach and cool mint, registering both sun and reflected water. The upper field of pinks, laid lightly so the ground shines through, reads as air touched by glare—perhaps a cliff reflecting light, perhaps the bright cobbles of a quay, perhaps simply the feeling of radiance. The canvas does not specify the hour by long cast shadows; it tells it by temperature.

Space Without Illusionism

Depth is achieved by overlaps, scale, and temperature rather than by linear perspective. The darker zone at right recedes because it is cooler and denser; the warm reds and pinks advance. The woman’s robe, painted with the highest contrast on the canvas, belongs to the immediate middle ground. Even so, the surface never ceases to be a surface. The viewer is invited to step into the image while remaining alert to the fact of paint.

Movement, Music, And The Eye’s Path

The painting invites a musical reading. The bright red bar is a cymbal crash; the blue marks on the robe are a recurring motif; the water’s dabs are a steady accompaniment. The eye follows these parts as one follows instruments in a small ensemble, sometimes attending to one line, sometimes to the blend. The bowed head and softly triangular posture of the figure give the music its key: a quiet and contemplative andante, warmed by sun.

Relation To Contemporary Works And Fauvist Peers

In 1905 Matisse was also painting boldly colored portraits such as “Woman with a Hat,” with zones of hair-raising green and salmon set against one another. “Woman Beside the Water” belongs to that same revolution but translates it to intimacy and landscape. Where Derain often kept outlines heavy and colors poster-strong, Matisse uses more reserve, more breathing space, and a subtler web of temperature shifts. The picture acknowledges Neo-Impressionism’s separated touches, Gauguin’s decorative flats, and Japanese patterning, yet it fuses them into a tone that is unmistakably his.

The Human Presence And The Psychology Of Attention

Because the face is only lightly declared—tilted, half-hidden by the hair knot and a stroke of warm orange—the woman becomes both someone and anyone. Her attention is turned downward, away from us, which invites rather than blocks empathy. The bowed head, the gentle vertebral curve, and the folded arms generate an inwardness unusual in Fauvist fireworks. Matisse achieves it not by shading or narrative but by the way warm and cool patches cradle one another around the figure. The painting’s psychology lives in temperature, not in expression.

Why The Painting Still Feels New

The canvas feels contemporary because it solves a perennial problem with modest means: how to visualize glare and intimacy at once. By letting the white ground participate, Matisse makes light an ingredient, not an afterthought. By drawing with color, he avoids hard borders that would isolate the woman from her world. By reducing description, he clears space for rhythm. The result is a picture that trusts sensation as a kind of accuracy. It neither illustrates theory nor hides the hand; it offers the viewer a method of looking that is both exact and generous.

Conclusion: Intimacy At The Edge Of A Shore

“Woman Beside the Water” compresses Matisse’s 1905 discovery into a tender scene. A human figure, a robe of calligraphic blues, a fringe of water, and patches of heat-struck earth are enough to build a world. Color orchestrates structure; the white ground lets that color breathe; brushwork keeps the day’s weather on the surface. The woman’s lowered head anchors the emotion of the canvas, but the true protagonist is the experience of light moving over things. In this small painting Matisse demonstrates that painting can generate its own atmosphere and that the quiet act of looking down into water can carry an entire revolution in art.