Image source: wikiart.org

The Street Made of Sunlight

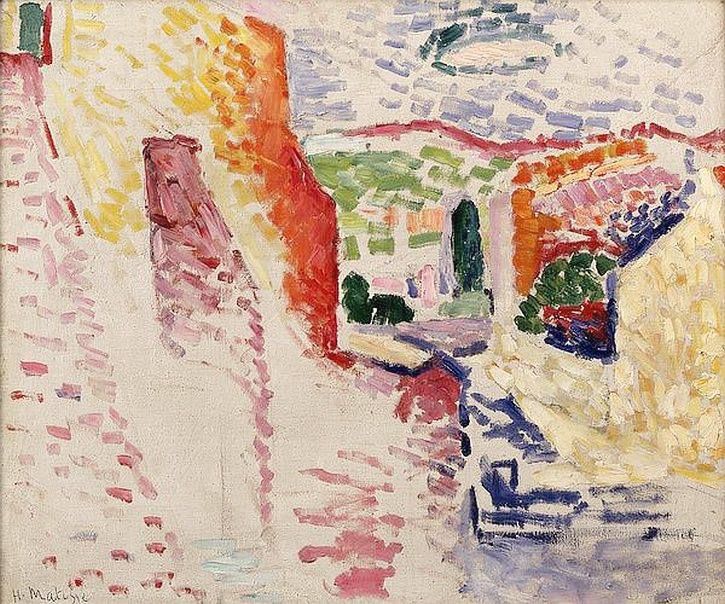

Henri Matisse’s “Sun Street” (1905) turns an ordinary alley into a spectacle of light. Instead of rendering façades, paving stones, and shadows with descriptive detail, Matisse builds the scene from dashes of unmixed pigment that leave ample bare canvas between them. The street itself is not a clearly drawn road but a whitened field, a blaze that swallows particulars. Color clings to the edges—scarlets and oranges on the left wall, yellows and ochres on the right, cool violets and blues along the lower right channel—and pools of green concentrate in the distant garden. The result is a picture in which sunlight is the protagonist and architecture is a set of chromatic scaffolds that frame it.

1905 And The Collioure Breakthrough

Painted in the fateful summer of 1905 at Collioure, “Sun Street” belongs to the cluster of works in which Matisse found the grammar that critics would soon call Fauvism. In that Mediterranean village, working closely with André Derain, Matisse abandoned tonal modeling and the quasi-scientific rigor of Neo-Impressionism for a freer deployment of high-key color. The goal was no longer to re-create nature faithfully but to translate sensation—heat, glare, and the quick shimmer of noon—into paint. “Sun Street” embodies that shift. It treats a narrow urban view with the same openness he applied to olive groves and sea views, insisting that the light bouncing in a street canyon can be as exultant as sunlight over water.

Subject And Setting

The motif is likely a back lane stepping downward toward a square or walled garden. A tall, warm-red plane at left reads as a sunstruck wall. Opposite it, a more variegated ochre mass suggests another façade or embankment. The central rectangle opens like a window onto a patch of green—trees, shrubs, perhaps a cypress—beyond a low parapet. A zigzag of blue and lavender strokes along the lower right edge hints at shadowed steps or a drainage runnel. Above, the sky is pierced with pale lilac and blue commas. There are no figures. The street’s vacancy heightens the intensity of light, as if noon has driven people indoors and left the elements to perform.

Composition As an Aperture

Matisse organizes the painting like an aperture that focuses brightness. Two strong verticals—the red wall on the left and the ochre mass on the right—narrow toward the middle distance, forming a corridor. But instead of using linear perspective to map recession, he relies on diagonals and color intervals. The warm left edge leans inward; cool tones gather on the right; both press the eye toward the square of garden green. The white expanse of the street functions as negative space that turns positive through sheer intensity. The whole composition reads as a funnel of light that empties into the sunlit core beyond.

Color As Architecture

Color builds the street’s architecture more decisively than contour. The left wall shoulders the composition with a spectrum from crimson to tangerine to lemon, each patch placed to sharpen the next. Opposite, a paler wall collects butter yellows, peach, and cream. These warm masses are counterbalanced by the cools—cobalt strokes in the sky, bluish violets in the steps or gutter, and a green mosaic in the garden. The complements are simple but potent: blue against orange, violet against yellow, green against red. The pairings regulate spatial feeling—warms advance and enclose, cools recede and open—without the need for detailed drawing.

The Vital Role of the White Ground

“Sun Street” is one of Matisse’s most eloquent demonstrations of reserve—the conscious decision to let primed canvas remain visible. The unpainted ground is not a gap; it is a blazing actor that carries the feeling of southern glare. By spacing his strokes and refusing to veil the surface with blended tones, Matisse allows light to seem intrinsic to the painting, as if radiating from within rather than merely hitting its surface. Nowhere is this more persuasive than in the great wedge of whiteness that constitutes the street. It is the image of sunlight and the literal exposure of canvas at once.

Brushwork and Tempo

The surface is made of short, brisk dabs—rectangular or comma-like—set at angles that follow the planes they articulate. On the left wall, the marks climb diagonally upward like heat shimmer; on the right, their direction switches and the rhythm loosens; in the sky, the dashes float horizontally; along the lower right, the strokes thicken and darken to state shadow. The tempo is quick but not chaotic. Density increases near the flanking walls and thins on the street, a measured orchestration that keeps the brightness from dissolving into blankness. The viewer feels the speed of execution and, with it, the urgency to capture the sensation before it fades.

Light, Hour, and Temperature

The title tells us the hour: not morning or evening but the steep light of noon or early afternoon. Shadows puddle in short, dark cools rather than stretching in long bars. The heat reads as chromatic pressure. Warm hues mass in the architecture, and even the cools carry energy; the blues and violets are saturated rather than gray. Matisse evokes the way midday brightness bleaches detail while intensifying color extremes, a perceptual paradox that the canvas performs by allowing white to dominate without weakening the palette.

Space Without Linear Perspective

Although the viewer senses depth—the corridor pulling toward the green square—the picture avoids the mechanics of converging orthogonals. Space arises from relative scale, temperature contrast, and the distribution of marks. The garden’s green is encased by red and ochre planes that step forward; the sky’s pale blue dashes ride high and thin; the blue shadow at the right edge anchors the foreground. This approach lets Matisse maintain the painting’s flatness—crucial to Fauvist design—while still granting the viewer a path to travel.

Urban Modernity Through Fauvist Means

“Sun Street” exemplifies how Matisse applied Fauvist language to modern urban subjects. Unlike pastoral landscapes that invite lyrical reverie, the street is a constructed space of brick and plaster, cut to catch light in dramatic ways. Matisse sidesteps anecdote and signage, choosing instead to turn the city’s geometry into color planes. The effect is at once contemporary and timeless: a specific nook in Collioure becomes an emblem of Mediterranean townscape, a place where people live by the clock of light.

Drawing With Edges of Color

Contour is minimized, but where separation is needed Matisse draws with color edges. A seam of scarlet hugged by lemon turns a corner on the left wall. A violet band against cream states the break between paving and step. A crisp green column inside the distant rectangle may indicate a tree or cypress; it also serves as a vertical latch holding the center in place. These edges do not behave like ink outlines; they are pieces of paint whose value lies in their adjacency. Form is therefore an event that happens between colors rather than within a line.

Comparison Within the 1905 Cycle

Placed beside “Madame Matisse in the Olive Grove” or “Promenade des Oliviers,” this canvas is sparer and more daring in its use of reserve. The olive-grove pictures vibrate with all-over dabs; “Sun Street” clears the central field, trusting the white ground to carry the glare. Compared with “Landscape in Collioure,” which steadies its high key with a commanding black trunk, “Sun Street” dispenses with heavy anchors and lets the flanking warms and cool shadow suffice. It is among the most distilled of Matisse’s Collioure works, closer in spirit to a poster or a stage backdrop than to an observational sketch.

From Divisionism to Free Syntax

The broken touch acknowledges Neo-Impressionism, yet the discipline has been thrown off. Rather than dots calibrated for optical mixture, Matisse uses variable strokes—some thick, some scumbled—to construct tempo and texture. He is not experimenting with scientific color theory; he is deploying a flexible syntax to express glare and heat. The lesson he keeps is clarity—clean pigments placed side by side. The lesson he discards is regularity. The street breathes because the marks are allowed to vary.

The Eye’s Walk Through the Picture

The viewer’s gaze enters from the bottom left, follows the pale lane upward, wavers at the red wall, and slips through the central opening to test the coolness of the garden. It then rises to the small blue oval cloud near the top center and drifts back along the lilac sky to the left margin. The route is simple but satisfying: approach, pass through, and return. Because there are no people to observe, looking becomes an embodied walk, a promenade organized by color thresholds rather than architectural signage.

The Ethics of Simplification

A hallmark of Matisse’s 1905 credo is his willingness to simplify in order to intensify. “Sun Street” eliminates windows, doors, bricks, and paving joints, keeping only what transmits the light event. This is not carelessness; it is economy. The reduction clarifies the relation between hot walls, cool shadow, and open sky, producing a clarity that descriptive detail would dilute. The painting’s power lies in what it refuses to include.

Materiality and Touch

The paint sits with enough body to catch raking light, especially in the warm walls and blue shadow. Elsewhere Matisse scrubs the pigment thinly so the ground participates, a technique that saves brightness and keeps the surface unified. The signature at the lower left is modest, nested among strokes rather than hovering above them, another sign that the artist considered the entire surface a single organism.

Why The Picture Still Feels New

More than a century on, “Sun Street” remains fresh because it captures an experience photography rarely grants: the sensation of being half-blinded by light. Cameras record the street; Matisse records the act of squinting, the way forms dissolve toward white while edges flare. The painting exhorts viewers to trust feeling as a kind of accuracy. It does not illustrate a theory; it demonstrates a way of seeing that many people know but seldom notice.

Anticipations and Afterlives

The bold use of reserve and color planes here anticipates later masterpieces in which color becomes architecture outright, culminating in “The Red Studio,” where red functions as both wall and air. The urban subject foreshadows Nice interiors, where windows blaze as rectangles of pure color. Even the poster-like clarity of “Sun Street” points forward to the cut-outs, in which shape and color collapse into one decisive gesture. The 1905 alley is thus a seedbed for decades of invention.

Conclusion: A Corridor Of Light

“Sun Street” shows Matisse discovering that a city’s narrowest space can become a theater of light. By allowing white ground to dominate, by composing with blocks of warm and cool, and by relying on the rhythm of brush marks rather than on linear perspective, he turns a modest Collioure lane into a manifesto for modern painting. The street is not a thoroughfare to somewhere else; it is itself the destination—the place where sunlight becomes form.