Image source: wikiart.org

Collioure, Summer 1905: The Fauvist Laboratory

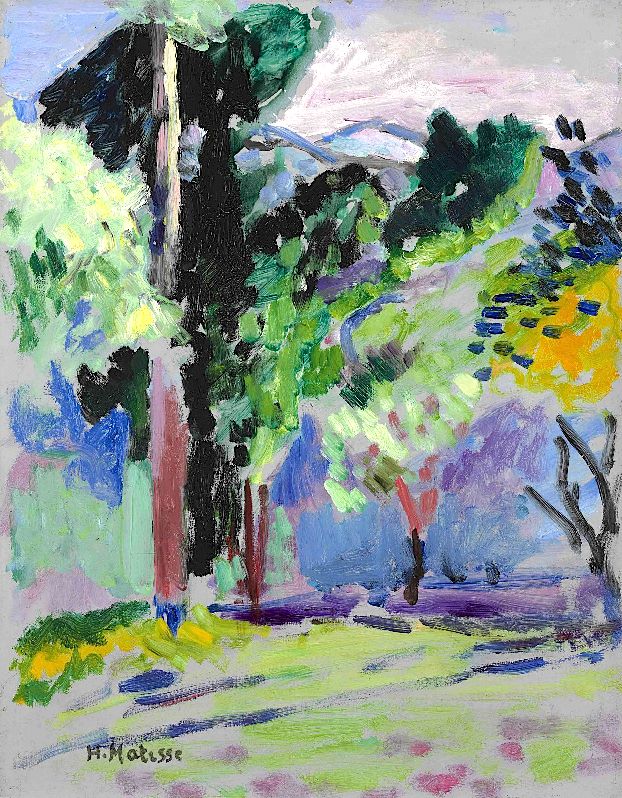

Henri Matisse painted “Landscape in Collioure” in 1905, during the blazing Mediterranean summer that forged the visual language later labeled Fauvism. In the small fishing town near the Spanish border, Matisse worked alongside André Derain and pushed color to act with unprecedented independence. Instead of building forms with tonal modeling, he set high-key pigments against one another so that hue, temperature, and contrast did the structural work of drawing. “Landscape in Collioure” belongs to this crucible. The motif is simple—trees, ground, distant hill, and a sliver of sky—yet the treatment is radical: the scene is constructed from blocks of saturated color, swift strokes loaded with paint, and bold darks that anchor the luminous field.

A Vertical Landscape That Feels Like a Stage

The composition is taller than it is wide, a vertical format unusual for expansive views but ideal for the upright thrust of trees. On the left rises a commanding trunk, nearly black, bisecting the picture like a stage prop pulled into place. Behind and beside it, a chorus of lighter, leaf-laden forms moves diagonally up and right, creating a sense of depth that is felt more than measured. A band of pale ground occupies the bottom third, where lavender and lime patches cast the vibration of shadow and glare. On the right edge, a white-gray tree with spare branches counters the weight of the dark trunk, giving the composition a seesaw balance. The result is a stage where the actors are trees, the lighting is color, and the plot is the day’s unfolding light.

Color As Construction Rather Than Description

Color does not merely decorate the forms; it builds them. Matisse organizes the canvas into warm–cool dialogues: lemon greens and warm yellows advance; lilacs, periwinkles, and cool blues slip back. Small swatches of orange peep through the foliage to intensify adjacent greens, and violet shadows run along the ground to hold the surface together. The sky is not a single field; it’s a set of pale notes—whites touched with pink and gray-blue—that keep the upper register light enough for the dark trunk to read as a firm silhouette. Everywhere complementary pairs—green/red, blue/orange, yellow/violet—quietly maintain the picture’s equilibrium. These oppositions are not textbook demonstrations; they are living relationships that give the scene air and stability.

The Expressive Role Of Black

One of the arresting features of the painting is the assertive use of black in the central tree. Many nineteenth-century colorists avoided black because it could deaden mixtures, but Matisse uses it as a catalytic presence. The black trunk stabilizes the high key of the surrounding palette, like a bass line under bright horns. It clarifies the composition by providing a crisp vertical, and it dramatizes the remaining colors by contrast. The small ivory stripe running down its center suggests reflected light without depriving the trunk of its mass. This is not an absence of color; it is color’s foil, allowing faint greens to glow brighter and gentle mauves to feel cleaner. The strategic black in “Landscape in Collioure” shows Matisse’s confidence in handling extremes.

Brushwork, Impasto, And The Energy Of Execution

The paint sits thick on the surface, often in quick rectangular touches that preserve the memory of the brush’s bristles. Some strokes, especially in the foliage, are pressed and lifted, leaving a broken edge that catches the light. Others, such as the lavender streaks in the foreground, are dragged thinly so the pale ground shines through. This varied handling produces a visual rhythm: dense, textured notes where he wants the eye to dwell; skimming, translucent passes where he wants it to glide. The painting communicates the speed of its making without feeling careless. Each swatch contributes to an overall pulse—the sense that sunlight is not static but constantly falling, ricocheting, and dissolving.

Light, Hour, And Atmosphere

The color temperature suggests mid-morning or late afternoon, when sun skims laterally and throws violet and blue shadows across light grass. The ground reads as a lime-tinted plane with cooler patches—shadows from off-stage trees or from the trunks within the scene. High in the picture, a wedge of pale sky presses down, squeezed by the leafy canopy. Matisse does not chase meteorological accuracy. Rather, he isolates the sensations that make Collioure distinct: bright dryness, resinous greens, and a light so clear that shadows are colorful rather than gray. The air feels warm but not heavy, a clarity that tends to simplification, which the painting embraces.

Space Without Illusion

Perspective is present but minimized. The path of the eye is directed by overlapping planes and by the recession of cool hues, not by a system of converging lines. The ridge or sea horizon in the far distance is a loose blue shape that feathers into the sky; it suggests distance without mapping it. Forms press toward the picture plane while still implying depth—an approach that would culminate later in Matisse’s interiors where tables tilt and walls behave like fields of color. In this landscape the balance is still tender: we feel we could step into the space even as we remain conscious of the painted surface.

Trees As Characters And Carriers Of Gesture

The trees are treated not as botanical specimens but as characters with distinct roles. The massive dark trunk on the left is a pillar, the stage’s proscenium. The reddish trunk beside it is a warm echo, softening the severity. The central cluster of foliage is rendered as a scatter of light green strokes broken by pockets of dark; it seems to vibrate, as if agitated by wind and heat. On the right, a pale-barked tree leans into the picture from the edge, its branches drawn with confident dark lines that punctuate the yellow canopy behind. These personified forms allow Matisse to choreograph the scene as a set of gestures—the trees bow, stand, and lean—so the viewer reads movement and relationship rather than static arrangement.

Edges, Reserves, And The White Ground

Matisse leverages the ground color of the canvas to keep the palette luminous. He leaves reserves—thinly painted or untouched areas—around and within forms so that white light flickers between strokes. This practice prevents colors from turning muddy and creates a halo effect that feels like glare. In the sky especially, thin scrubs of blue and lilac allow the ground to participate actively. The unpainted moments are not voids; they are structural light. They create the palpable Mediterranean brightness that would be difficult to achieve with pigment alone.

Between Neo-Impressionism And Fauvism

The touch in “Landscape in Collioure” remembers divisionism—short, discrete marks that animate the surface—yet it loosens and thickens those marks until they become painterly rather than scientific. Matisse abandons the notion that optical mixtures must obey a system of primaries. He chooses hues for their expressive function and lays them so they interact as chords. The result is a canvas that feels both carefully tuned and freely spoken. It acknowledges the lesson of Seurat and Signac while showing why Matisse had to move beyond them: the world is not only an optical phenomenon; it is also an emotional one, and paint can speak that directly.

Nature Reimagined As Felt Accuracy

If we were to demand topographic exactness, little here would satisfy: the sky’s pinks, the black trunk, the blue-green shadows—none is “correct.” And yet the picture feels true because it captures how a bright day simplifies perception into large color zones. Under such conditions the eye often foregoes texture and detail; it registers contrast and temperature instead. Matisse translates that perceptual fact into a method. Green is not the “true” color of leaves; it is the active participant that makes the neighboring mauve shadow vibrate. Violet is not the “color of shade”; it is the necessary complement that steadies yellow’s glare. Accuracy is relocated from the realm of description to the realm of effect.

Comparisons Within The Collioure Cycle

Seen alongside other 1905 works, this painting clarifies Matisse’s range. In “The Open Window,” he organizes an interior-exterior exchange with a lattice of verticals and horizontals; in “Madame Matisse in the Olive Grove,” he explodes the surface into dabs that breathe; in “Promenade des Oliviers,” he orchestrates a central path between two trees. “Landscape in Collioure” sits between these extremes: it retains a strong central axis—the black trunk—yet keeps the brushwork more blocklike than dotted. It is quieter in narrative terms but decisive in structural ones. The painting functions as a keystone for the series, showing how a single dark mass can stabilize a high-key world.

Material Realities: Canvas, Pigment, And Touch

The material presence of the painting matters to its meaning. Thick impasto in the tree trunks creates ridges that catch ambient light, so the picture physically changes as one moves before it. The greens are likely mixes of viridian with yellows; the purples, combinations of ultramarine and carmine; the blacks, perhaps crushed carbon laid dense. Whatever the exact pigments, Matisse allows them to behave as substances, not just colors. He does not polish away brush traces; he keeps them visible, evidence of speed and decision. The signature at lower left sits within the color field rather than floating above it, another reminder that name and image share a single material reality.

The Poetics Of Simplification

Simplification in this painting is not avoidance; it is strategy. The land is reduced to planes, the foliage to masses, the sky to veils. Each reduction clarifies a relationship: vertical against horizontal, dark against light, warm against cool. Through subtraction Matisse achieves openness—the pictorial equivalent of clean air. The eye is not crowded with incident; it is invited to experience broad forces. This approach anticipates his later interiors where furniture collapses into shapes and color becomes architecture. “Landscape in Collioure” is an early proof that radical simplification can yield richness rather than poverty.

A Landscape About Looking

The painting is also a study in how vision moves. The viewer’s gaze rises with the black trunk, drifts right along the line of canopies, and descends across the pale ground, where lavender streaks pull it back toward the starting point. The loop repeats, like walking a small circuit under the trees. Because the marks are legible as marks, the viewer remains aware of the painter’s own looking—quick, selective, energized by light. We are not merely seeing a grove; we are witnessing a way of seeing, and by following its paths we rehearse it ourselves.

Why A Small Scene Feels Monumental

The painting’s subject is modest, yet it resonates beyond its size because it declares a principle: color can carry structure, emotion, and atmosphere all at once. The black trunk is a column; the greens and violets are air; the yellows are sun; the lavender ground is shade. With a handful of elements Matisse conjures the feel of a place and a time of day. The economy is bracing. Nothing is decorative in the superficial sense; every patch earns its keep. That concentrated rightness gives the canvas the gravitas of a larger work.

Legacy And Anticipations

This landscape foreshadows key moves in Matisse’s later career. The reliance on color relationships to build space leads to the saturated rooms of 1908–1911 and ultimately to the radical compression of “The Red Studio.” The confidence with black portends the bold outlines in his Nice period and the decisive contours of the cut-outs. The simplification of natural forms into graphic masses anticipates the dancers and bathers, where bodies are reduced to rhythms rather than anatomies. “Landscape in Collioure” thus reads as both a culmination of a summer’s experiment and a seedbed for decades of invention.

How To Look At The Painting Today

For contemporary viewers inundated with photographic images, the painting offers a recalibration. It asks us to trade literal detail for the pleasure of relations: how a patch of purple cools a field of yellow; how a small gray wedge can open the sky; how a single black vertical can hold a whole scene together. It also invites slowness. The apparent speed of the brushwork does not license a quick glance; the picture rewards lingering, letting the eye acclimate to its temperature shifts and subtle balances. Looking becomes a kind of promenade—one that begins at the canvas edge and wanders through its color weather.

Conclusion: A High-Key Grove And A New Way Of Seeing

“Landscape in Collioure” captures the moment when Matisse learned to let color lead. A grove near the sea becomes a lesson in structure, light, and economy, taught not by linear perspective or meticulous shading but by the interplay of high keys and strategic darks. The vertical format, the commanding black trunk, the quick blocks of leaf color, the lavender shadows on acid grass—each decision nudges painting away from description and toward experience. What remains on the canvas is not just a place in southern France but a method for looking: trust color, simplify forms, make space breathe, and let the viewer feel the day.