Image source: wikiart.org

The Promise Of Morning In Matisse’s Fauvist Year

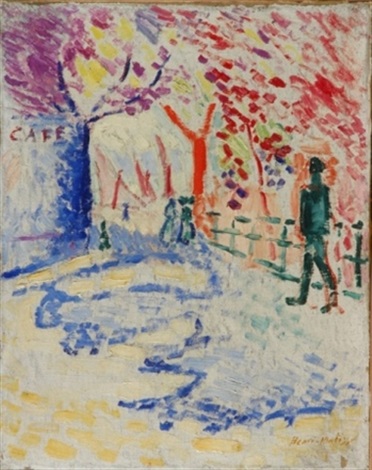

Henri Matisse painted “A Beautiful Summer Morning” in 1905, a year that transformed his career and, with it, the course of twentieth-century painting. The canvas captures a pedestrian scene—trees lining a promenade, the word “CAFÉ” lettered on a trunk, a figure moving along a railing—yet it feels more like an exclamation than a description. Morning sun seems to break open the surface, and color, rather than line, carries the action. What appears modest in motif becomes radical in method: Matisse turns the difference between warm and cool hues into a structure as solid as architecture, letting paint itself stage the feeling of a day beginning.

Historical Setting And The Birth Of Fauvism

The year 1905 is synonymous with the rise of Fauvism. That summer in Collioure, on the Mediterranean coast, Matisse and André Derain pursued a new grammar of color. They dropped the calibrated dots of Neo-Impressionism and the sober tonalities of academic taste. Instead they allowed pigment to behave with maximum freedom—laid in brisk, non-naturalistic hues that announced emotion as the primary logic of the picture. “A Beautiful Summer Morning” belongs to this breakthrough moment. The subject is modern life in passing; the style is all declaration. When viewers at the Salon d’Automne later that year encountered these high-key canvases, the shout of color earned the painters the label “wild beasts.” This work embodies why: not because it is violent but because it is fearless in letting color do what drawing used to do.

Subject And Setting: The Lived Scene

The motif is simple and recognizable. A walkway curves in from the lower left and swings to the middle distance, suggesting a small square or a shaded avenue. Trunks and branches vault overhead, and the letters “CAFÉ” tilt across the blue-violet shape of a tree at left, turning the trunk into a signboard. A railing parallels the path on the right. A solitary figure strides forward, rendered in a dark, green-black silhouette with a crimson accent at the feet, as if the shadowed body still carries the heat of morning in its step. Two smaller figures cluster farther back, their forms barely described, more like chords of color than people. The scene is not a topographical record; it is a memory of light colliding with place.

Composition As A Dance Of Diagonals

Matisse organizes the canvas as a set of crossing diagonals that lean the eye forward. The path’s oblique sweep from bottom left toward the distance tilts the picture into motion; the right-hand railing counters with a parallel that steadies the tilt. Trees rise in verticals that soften as they meet the exploding canopy of leaves, and the entire upper half of the painting vibrates with slanted dabs. The figure’s movement to the right echoes and completes these diagonals. There is perspective here, but it is constructed as a rhythm rather than a measured recession. Spatial depth becomes the by-product of repeated color strokes rather than the product of converging lines.

Color As Structure

The audacity of the palette carries the meaning. On the left, a tree swells in strokes of lavender and ultramarine, whispering shade. Across the top and right, hot pinks and oranges flare, announcing the arrival of sunlight through foliage. The ground is laid in pale yellows and creamy whites, punctuated by cool blue shadows that skip like reflections from a rippled surface. The walking figure is almost entirely dark green, yet Matisse plants hints of red at the edges and in the path so that complementary contrasts buzz against one another. No hue is simply descriptive. Blue is not “the color of shadow” and red is not “the true color of a trunk”; each note is chosen for what it does to its neighbor. Color becomes a skeleton, a scaffolding, a way to lock together the scene without relying on contour.

The Light Of Morning

Matisse’s title invites us to read the atmosphere with attention. Morning light is not yet vertical and harsh; it arrives laterally, washing across surfaces in long strokes. The cooler notes at left imply the shade of early day, before the sun clears the buildings, while the right side bursts with the pinks and vermilions of first light bouncing from leaves and façades. The painting therefore catches not simply “trees and a walker” but a moment when the air itself changes temperature. The sensation of cool to warm is mirrored in the shift from blue to red across the composition, a chromatic sunrise unfolding on the canvas.

Brushwork And The Material Of Paint

The strokes remain visible, short, and assertive. They do not blend into a polished skin; they stack and jostle like tesserae. This mosaic of touches evokes Pointillism yet refuses its optical rules. Instead of discrete dots that mix in the eye, Matisse uses rectangular jabs and quick dashes that leave the white ground peeking through. The unpainted flecks brighten the whole surface, letting air into the color. The effect is at once casual and deliberate: casual because the marks look spontaneous, deliberate because their pattern sustains the entire composition. Paint is not a veil over forms; paint is the form.

Drawing Without Drawing

Matisse minimizes contour. Few outlines separate figure from setting; edges are formed when one field of color meets another. The walker is not encircled by a line but by the pressure of surrounding hues. This method eliminates the hierarchy that would privilege figure over ground. The café sign is formed by simple strokes of darker pigment against lilac, and even the letters feel temporarily suspended, as if words, like bodies, are just patches of paint. By denying outline, Matisse frees the viewer’s eye to travel without interruption, the way one strolls through a square without noticing boundaries until the light changes.

The Rhythm Of Movement

Everything in the picture moves. The stride of the figure anchors the tempo, but motion runs through the canopy as well, where red and pink dashes rustle like leaves stirred by an onshore breeze. Shadows on the path curve in looping arcs, suggesting both the sweep of morning and the casual meander of a person with nowhere urgent to be. The viewer feels invited to step in, to walk along the curve of the path and pass beneath the threshold of color where shade becomes sun.

The Café As A Modern Emblem

The painted word “CAFÉ” matters. It inserts the everyday vocabulary of the city into a work of high art. In 1905 cafés were the living rooms of public life, places where artists argued about color and readers absorbed the news. The letters anchor the scene in modernity while also acting like a poster pasted onto a wall. They recall the influence of graphic design and advertising on avant-garde painters, and announce Matisse’s ease in letting language share the surface with trees and people. The café is a promise of social encounter at the edge of morning, and the picture, like the sign, offers an invitation.

A Dialogue With Impressionism And Beyond

This work converses with Impressionism yet goes beyond it. The short strokes and attention to light recall Monet, Pissarro, and Sisley, but Matisse is not content to register how light falls on stable forms. Instead he lets color rethink the forms themselves. The tree becomes violet because violet intensifies the yellow ground; the sky is a filigree of white because white heightens the adjacent red. Where Seurat had asked the viewer’s eye to blend pure hues into naturalistic tones, Matisse asks the eye to accept unblended, resonant chords as reality. The scene is not an optical experiment so much as a new social contract between painter and viewer: believe in color’s authority and the world becomes more vivid.

Morning As Metaphor For A New Style

The title does more than describe time of day; it sets a metaphor for renewal. Morning is the first act, the beginning of activity, the hour when choices feel wide open. In 1905 Matisse was reinventing his approach, shedding earlier experiments and arriving at a language he could call his own. The canvas looks like that decision feels: fresh, decisive, and exploratory. The walker’s stride reads as an emblem of artistic momentum. Even the incomplete rendering of the background figures hints at a future still being sketched, a day about to unfold.

The Role Of The White Ground

The painting’s luminosity depends on the white ground left exposed between strokes. Those small intervals are not gaps; they are active participants. They let adjacent colors breathe, keep mixtures from turning muddy, and amplify the sensation of light bouncing off stone and leaves. The white ground also binds the disparate hues into a single atmosphere. Instead of glazing or blending, Matisse uses absence to produce unity. Morning light, after all, is as much air as it is color, and the visible ground lets air into the image.

Edges, Corners, And The Feeling Of A Snapshot

Notice how the drama pools near the edges. The café sign hugs the left margin; the figure approaches the right edge; the canopy erupts at the top. The composition feels cropped, as if the painter glimpsed an instant and quickly pinned it down. This cropping device heightens the sense of immediacy and makes the space feel continuous beyond the frame. The viewer senses that just out of sight more trees, more pedestrians, more sunshine await, the way a morning promises more life than any single glance can contain.

The Psychology Of Color And Mood

Red and pink in the upper right do more than mimic leaves lit by sun. They stir an emotional response associated with warmth, joy, and heightened attention. The lavender and blue at left bear the calm of shadow. Between them a spectrum of yellows and creams acts as mediator, suggesting a livable ground on which the day will proceed. The lone walker, rendered in dark green, supplies a counterweight. The eye returns to that silhouette the way a person in a square would register another body moving nearby. Matisse achieves balance: exuberance in the air, steadiness on the ground, a poised human presence threading them together.

Memory, Observation, And The Studio

This sort of painting often merges direct observation with reconstruction in the studio. The spontaneity of the strokes suggests a painter working rapidly to grasp a sensation before it fades, yet the underlying structure implies careful revision. The arc of the path and the echoing railing do not feel accidental. Matisse’s practice in 1905 often involved quick outdoor notes developed into larger statements indoors. “A Beautiful Summer Morning” has the clarity of a distilled recollection, a scene remembered for what it made the painter feel rather than for what every surface actually looked like.

The Figure As Every Walker

The protagonist is anonymous, nearly faceless, and simplified to essential masses. That reduction turns the figure into a stand-in for any viewer entering the day. The dark tone sets the person off from the higher-key environment, but the green connects the body to the vegetal world around it, suggesting that human movement and natural rhythms are synchronized. We sense that the figure is both part of and apart from the scene, an observer who also contributes to the city’s pulse.

The Tension Between Urban And Arboreal

Matisse places a café sign and a railing beside trees in full leaf. The painting is not a pure landscape; it is a modern threshold where built and natural environments meet. Morning belongs to both domains: workers and flâneurs emerge into streets while birds shake the night from the canopy. That hybrid setting suits the painting’s stylistic hybridity: it shares Impressionism’s outdoor attention while absorbing the graphic clarity of posters and the expressive liberation of Symbolist color. The result is a space where culture and nature trade energies.

Technique, Speed, And Control

The touch looks quick, but speed does not mean carelessness. Matisse distributes his saturated notes with discipline, reserving the most intense reds and magentas for areas that must project, and anchoring the left with cooler zones so the composition does not topple. The density of strokes thickens where he wants focus—the canopy, the figure’s path—and thins elsewhere to keep the eye moving. The control is invisible because it is folded into the rhythm of the marks. This is one of Matisse’s gifts: to make orchestration feel like improvisation.

What The Painting Meant In 1905 And What It Means Now

In 1905 such audacity of color signaled a new freedom: painting could detach from the duty to resemble and instead aim to persuade—to convince viewers that the energy of life could be carried by pure chromatic relationships. Today the work still feels fresh because it captures a universally recognizable sensation: the way a bright morning simplifies decisions, the way forms seem to resolve into bold planes, the way walking through light can reset the mind. The painting does not instruct us to look at a specific place; it teaches us how to feel color as experience.

Legacy Within Matisse’s Trajectory

“A Beautiful Summer Morning” prefigures many later achievements. The reliance on color to build space foreshadows “The Open Window,” the portraits with unorthodox hues, and ultimately the paper cut-outs where color becomes shape outright. The willingness to let language appear on the picture plane anticipates his later interest in decorative scripts and studio signs. Above all, the trust he places in the viewer’s eye—inviting us to complete forms from intervals of pigment—becomes a principle that sustains his practice for decades.

Why This Modest Scene Is Monumental

Nothing heroic happens in the picture. No myth, no grand narrative. Yet the work is monumental because it states with clarity that ordinary life, apprehended through color, can be as compelling as any historic drama. The painting’s bravery is quiet: it asks you to accept that a violet tree and a crimson branch can convincingly render shade and sun, that a dark green silhouette can embody a morning’s purpose, that the simplest walk toward a café can feel like the avant-garde entering the day.

Conclusion: The Morning After The Night Of Tradition

“A Beautiful Summer Morning” offers more than a pleasant view. It is a manifesto disguised as a stroll. In 1905 Matisse recognized that the tradition of modeling and exact description had become a kind of midnight, and that a different day could break if color were allowed to lead. Here, morning arrives as a sequence of chromatic decisions that clear the air and set the eye in motion. The viewer leaves the painting with the renewed pleasure of attention, as if stepping out of a doorway to find the street glowing and the café ahead welcoming, and knowing that the day’s beauty is not behind us but beginning.