Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

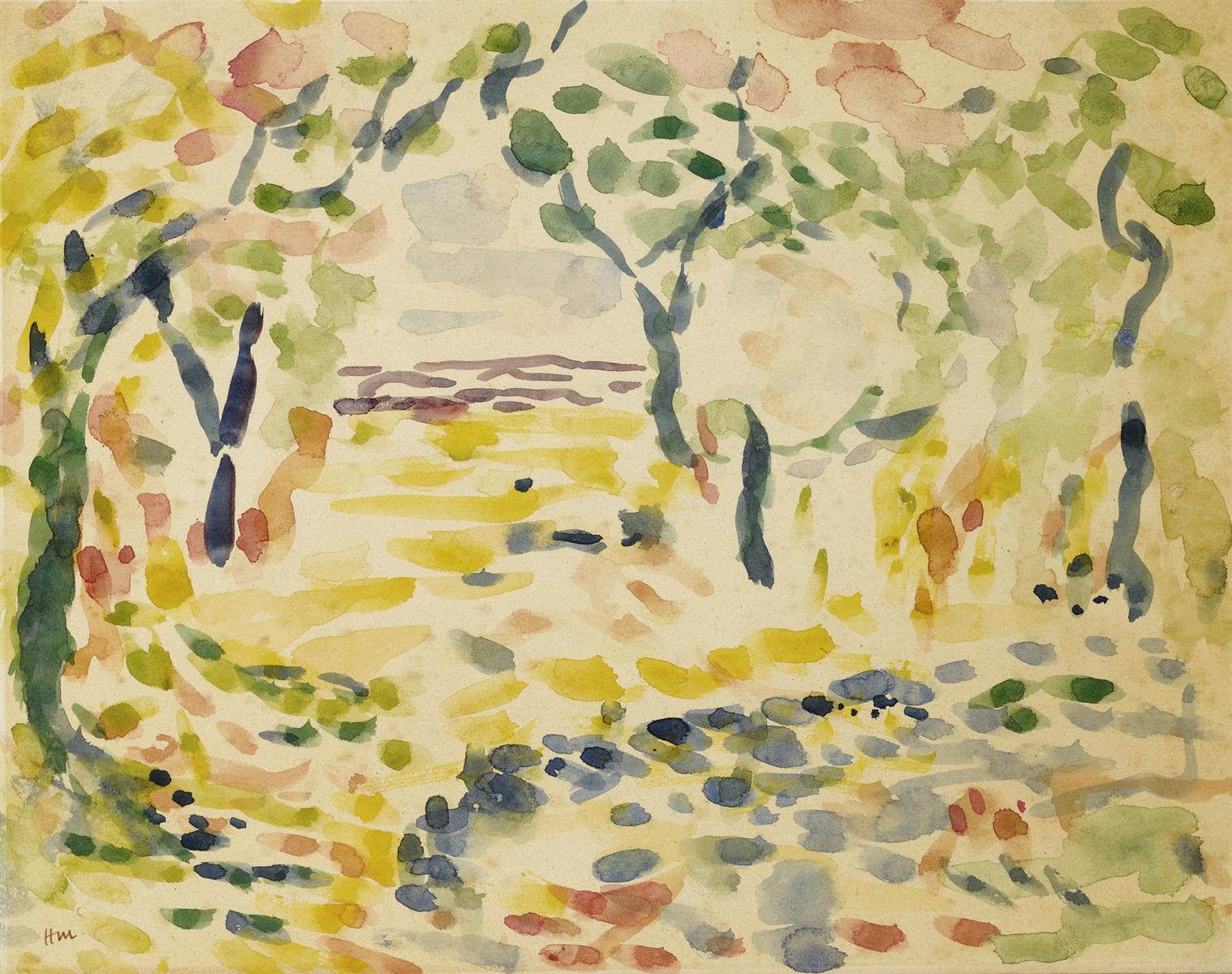

“Study for ‘The Happiness of Living’” from 1905 captures Matisse at the threshold of his breakthrough. Even in this modest sheet, the artist orchestrates a world with little more than translucent daubs of color. The page breathes; the paper’s creamy white becomes sunlight; the sparse marks behave like notes in a melody, giving time and direction to an imagined landscape. What you see is not a finished tableau but a living proposition, a quickened rehearsal for one of the defining images of early modernism, the large oil “Le Bonheur de Vivre” (The Happiness of Living) completed in 1905–1906. This study shows how Matisse tested the grammar that would allow color alone to carry structure, mood, and meaning.

The Historical Moment

In 1905 Matisse had just returned from the incandescent light of Collioure, where he worked alongside André Derain. There he shed the last remnants of naturalistic modeling and embraced a language in which pure color and simplified forms could stand as equivalents for sensation. The same year he would exhibit at the notorious Salon d’Automne, where a critic’s quip christened the “Fauves,” or “wild beasts.” This study belongs exactly to that pivot: it retains hints of Neo-Impressionist division but loosens the method into something freer, more responsive, and palpably human. Rather than small, scientific dots, he lays down larger, breathing touches that admit accident and speed. The sheet lets us watch his hand and mind discover a path away from rule-bound optics toward an art of feeling.

Subject and Compositional Armature

At first glance the page looks like a scattering of leaf-shaped spots in yellow, green, blue, rose, and violet. The more you look, the more plan emerges. Two open tree forms arc in from the sides, creating a natural proscenium and framing a luminous clearing at center. A slim horizon, mauve against the pale sky, pins the far distance. The lower half of the page is strewn with cooler blues and violets that read as dappled, shadowed ground. The upper half warms and thins, so that the eye rises through air to light. The composition is therefore classically built: foregound, middle, distance; left and right aisles; a center stage bathed in radiance.

This stage is not empty. It is a space of possibility. In the finished oil, Matisse will populate such a clearing with bathers, lovers, and a ring of dancers, but the study stops at the threshold of invention. That refusal is revealing. He is not yet interested in narrative; he is searching for a site where happiness could be plausible, an architecture of openness and shelter. The flanking trees feel like companions rather than borders. The path-like bands that sweep inward promise arrival without the coercion of linear perspective. Everything is invitation.

Color as Structure

The color choice is purposeful. Lemon and honey yellows occupy the center and lead toward the horizon, staging the picture as a zone of warmth and ease. Greens, from mint to olive, coil around and within the trees, crafting volume without contour. Cerulean and indigo appear where weight is needed—at the bases of trunks, along the shaded ground—so that the page does not float away. Small touches of rose and brick punctuate the canopy and the earth, tuning the spectrum and preventing the green-yellow scheme from becoming monotone.

Matisse treats complements as engines. The blues steady the yellows; the reds aerate the greens. He does not chase accurate foliage so much as balance. Each color answers another across the sheet, and the white left in reserve acts as both light and air. In the oil painting that follows, these correspondences will guide where bodies lie and where shadows fall. Here they prove that a landscape can be built from harmonies rather than outlines.

Technique and the Meaning of the Mark

The medium—watercolor and wash—allows Matisse to think at the speed of perception. You can see where a brush, still wet, kisses the paper and then fades, where a loaded stroke blooms against a previous wash, where a nearly dry touch grates across the surface and leaves a grain. Occasionally a stroke doubles back on itself, leaving a darker head at the end like a comma. These are not incidental textures; they are records of decisions. The discipline is not to correct. When a dab lands slightly off, Matisse lets the miss remain, and in doing so increases the liveliness of the whole.

That tolerance for accident is central to the study’s character. He turns watercolor’s reputed fragility into firmness by refusing to fuss. The speed of execution becomes a virtue, replacing the static perfection of a studio finish with a sense of ongoingness. The painting looks as if it might continue beyond the borders; our seeing completes it.

Space Without Perspective

Traditional landscape often marshals receding lines or tightly modeled forms to convince us of depth. Matisse proposes another kind of space, made from temperature, density, and rhythm. Warm, thinly painted areas advance; cool, denser ones recede. Clusters of marks slow the eye as surely as a thicket would slow a walker, while open swaths accelerate our passage into the distance. The horizon, reduced to a faint lavender band and a breath of sky wash, does surprisingly heavy work. It halts the forward pull just enough to make the central clearing feel held and habitable. Space becomes experiential rather than diagrammatic; you feel where you could stand, where you might rest, and where you would step next.

Rhythm, Dance, and the Promise of Figures

Even without a single body, the sheet moves like a choreography. The marks swerve, echo, and answer one another across the page; clusters resemble beats in a measure. The arcs of the side trees bend inward like arms, and the peppering of blue ovals across the ground suggests footfalls. In “The Happiness of Living” these suggestions will become explicit as Matisse strings figures into arabesques that twist and recline across the grass. The study is therefore less a landscape than a score awaiting performers. Its cadence tells you what kind of dance will unfold: not a march, but a gentle, spiraling, continuous flow.

Drawing with Color and the Use of Negative Space

There is almost no graphite line here. Matisse draws with color, letting a string of strokes stand in for a contour or a block of wash define a mass. The paper’s untouched white does crucial work. It becomes high sun on the clearing and glimmering intervals between leaves. That white is not emptiness; it is the brightest pigment in the palette. By relying on it, Matisse refrains from muddying his greens and yellows with added light tones. He is already practicing the economy that will later make his cut-outs so clarion: put down only what is necessary and let the ground sing where it can.

From Observation to Arcadia

Look closely at the right-hand tree and the left cluster of foliage. They feel seen—plausible in their branching and the way touches thicken where leaves overlap. Then notice how quickly the marks become generalized as they move toward the center. Matisse begins with observation and moves toward an imagined clarity. He distills the essence of shade and glare, enclosure and opening. The process mirrors the larger ambition of “The Happiness of Living,” which converts the real Mediterranean into an Arcadia of modern life. The study is a bridge, carrying empirical seeing into a vision of sovereign ease.

Emotion and Sensation

Because the sheet is so spare, emotional tone depends on the behavior of color. The prevailing yellows have a pastoral calm, but their translucency keeps the mood from becoming heavy. The cool blues carry a hint of melancholy that sweetens the joy without dampening it. Rose and terracotta flashes are like laughter heard at a distance. Nothing is forced. The mood floats, as light as air in late afternoon, and that lightness feels earned rather than decorative. Matisse is careful to leave enough unpainted space that the scene can breathe. Happiness here is not exuberance alone; it is equilibrium.

Relationship to Divisionism and Fauvism

The broken touches recall Neo-Impressionism, but Matisse has already discarded its mechanical regularity. His marks vary in size, tilt, and saturation; they function as expressive syllables rather than uniform units. At the same time, the daring of his palette—the confidence with which he assigns blues to ground shadows and uses cool green to describe tree trunks—announces the Fauvist spirit. Color is no longer a slave to local description; it is a free agent that builds the world according to felt necessity. The study stands at this crossroads, proving that a painter could absorb and surpass scientific color by trusting the authority of perception.

Preparatory Purpose and Differences from the Final Oil

Comparing the study to the later oil underlines what Matisse needed from such a sheet. He is not mapping figures or particular branches; he is testing a climate. He measures how much yellow the paper can bear before it washes out, how strong the blues must be to anchor the bottom edge, how far the trees may bend before the center closes. In the oil, figure groups occupy the glade and make its invitation explicit. In the study, the invitation is abstract, but perhaps more radical because of that abstraction. We sense that joy is possible before we are told what kind. The study stakes the claim that the emotion of a place can precede its narrative.

Craft, Restraint, and the Courage to Stop

Watercolor punishes overworking. Matisse’s success here rests on the courage to stop short of finish. Many artists would be tempted to explain the trees, to seal the sky into a coherent field, to model a path. He declines. By doing less he achieves more. The viewer’s eye fills in missing links; the imagination does part of the labor and thereby owns part of the picture. That collaboration between artist and spectator will be a hallmark of Matisse’s career, visible from the airy interiors of the 1910s to the radical cut-outs of the 1940s. The seeds are on this page.

Light as Subject

More than scenery, the subject is illumination itself. You can sense how the sun sifts through leaves, how ground and air trade colors as the eye adjusts. Because the washes are thin, some strokes glow from within; they seem lit, not merely colored. That effect is heightened by the decision to keep the sky nearly unpainted. The slightest cool veil suffices. As in his best work, Matisse suggests that light is not something added to a view; it is the condition by which a view comes into being. This insight, simple and profound, liberates the painting from imitation and roots it in perception.

Connections Forward and Back

Seen backward, the study converses with his 1904 Saint-Tropez works, where he had tested divisionist touches in seaside light. Seen forward, it anticipates the wide, unmodeled zones and codified arabesques that give “The Happiness of Living” its paradisal authority. It also points toward his later simplifications: the Nice period, where flat fields of color enclose figures; and the cut-outs, where paper shapes float in luminous balance. The constant across these changes is faith in color as a structural agent. This small sheet, with its few dozen strokes, declares that faith with clarity.

How to Look at This Study

Begin by letting your eyes rest in the central clearing. Feel how the yellow opens and the horizon steadies your gaze. Move outward along the arcs of the trees; notice how the marks thicken where shade would be heaviest, then thin toward the tips. Drop to the lower edge and trace the chain of blue ovals. As you follow them they begin to feel like steps leading in. Now return to the whole and register the way the page tilts toward invitation. Nothing bars entry. If you imagine figures moving into view, you are already participating in the painting’s generative act. The study is a device for imagining happiness, and the viewer completes its circuit.

The Work’s Lasting Significance

Why does such a slight object matter? Because it exposes the engine inside one of modern art’s most influential pictures. It shows that paradise, for Matisse, is not a fantasy imposed on the world but a clarity found within it. It shows that economy can heighten intensity, that pleasure can be lucid rather than anesthetic, and that color can do the heavy lifting once reserved for line and shadow. Above all, it reveals a method grounded in trust—trust of sensation, of the medium’s nature, and of the viewer’s intelligence. That trust radiates through the study like light through leaves.

Conclusion

“Study for ‘The Happiness of Living’” is a tender manifesto. The marks appear casual, almost offhand, yet they carry the architecture of an entire vision. Trees bend like welcoming arms; the center blazes with quiet promise; the ground hums with cool aftertones. Without drawing a single body, Matisse composes the conditions for joy and invites us to enter. The finished oil would make that invitation explicit, peopling the clearing with lovers and dancers; the study makes it elemental, proving that happiness can be built from breath, color, and the courage to leave well enough alone. The page is not a preliminary; it is a proposal for how painting might feel when it is most alive.