Image source: wikiart.org

A turning-point landscape from Matisse’s pre-Fauvist years

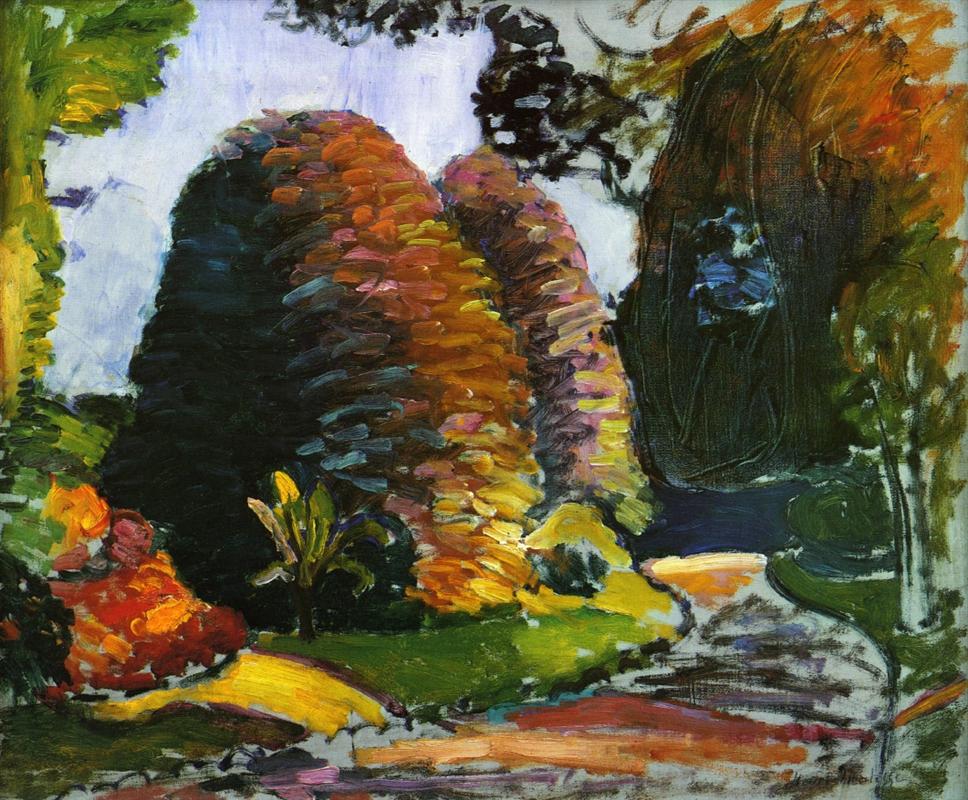

“Luxembourg Gardens” from 1903 belongs to the decisive moment when Henri Matisse was loosening the grip of tonal naturalism and discovering that color and surface rhythm could organize a picture more powerfully than detailed description. The Paris garden was a favored testing ground: a cultivated park inside a modern city, full of clear shapes, clipped trees, curving paths, and patches of light that shift by the minute. In this canvas Matisse converts that familiar setting into a laboratory for vivid contrasts and simplified masses, anticipating the breakthroughs of 1905 while retaining the weight and gravity of his studio training.

What the painting shows at a glance

The composition centers on a pair of rounded, hive-like tree masses that rise from the lawn like sculpted topiary. A path bends from the foreground toward the right edge, then slips into a darker grove. The left side of the canvas carries a cushion of warm foliage that flares orange and red, while the right side darkens into a deep green wall with a small, surprising, blue aperture. Above the trees the sky breaks open in pale lavender and white. Everywhere the forms are built from short, loaded strokes that stack like tiles, so that foliage reads as both leaves and pure paint.

The geometry of masses and the curve that conducts the eye

Matisse organizes the rectangle with a dialogue between vertical masses and a long curving arabesque. The two central trees are nearly symmetrical, not as mirrored twins but as related volumes that anchor the surface like pillars. They are counterweighted by the dark, almost architectural clump at the right edge. Across this structure a single S-curve carries the viewer: it begins as the pale path in the foreground, dips at the painting’s midriff, slips behind a light berm, and reappears as a dark, pooling lane that vanishes into the shadowy stand of trees. That curve is the painting’s conductor. It orchestrates changes in texture and temperature, guiding the eye through zones of heat and coolness, thickness and thinness, glow and gloom.

Color architecture and how temperature does the heavy lifting

The palette is anchored by complementary oppositions. Warm oranges, rusty reds, and yellow greens glow along the left and center; deep viridians, bottle greens, and blue-greens occupy the right. The central tree pair is a scale of oranges glazed with violets and mauves, suggesting foliage turned by autumn light yet refusing to pick out individual leaves. The sky is not a descriptive blue but a milky, lilac-toned light that lets the warm foliage flare. Matisse avoids black for the most part, achieving depth by cooling and lowering the chroma rather than by dirtying the color. As a result, the painting breathes. The darks are alive, the lights never chalky, and the transitions across planes take place through temperature shifts rather than sudden value cliffs.

Light as climate instead of spotlight

This is a garden under an even, high illumination, not a staged sunbeam. The white-lilac sky implies a thin cloud cover scattered with light; the lawn and path reflect that light upward in cool tints. Highlights are rarely pure white. Instead they are yellowed or cooled so that they carry the atmosphere of the scene. Even the brightest patches of path keep a veil of lavender or gray, preserving the unity of the whole. By treating light as a climate, Matisse frees the color to do structural work and prevents theatrical contrast from interrupting the surface rhythm.

Brushwork that turns nature into music

Look closely at the central trees and you see the brush acting like a musician’s wrist. Strokes are short, elliptical, and stacked with deliberate direction. Their repetition generates a tremolo, a visual vibration that evokes both foliage and the act of painting. In the warm bush at lower left, the strokes are chunkier and more angular, which makes that mound read as closer and denser. Along the path, the brush slides more horizontally, sometimes scraped thin so the grain of the canvas participates in the shimmer of light. In the right-hand grove the touch grows broader and more scumbled, allowing the forms to sink back. The variety is not decorative showmanship; it is Matisse’s way of translating different sensations—bark, hedge, grass, air—into a single grammar of mark-making.

Drawing by adjacency and the role of contour

Edges in this painting rarely come from a dark outline. They arise where one color meets another at a particular temperature or value. The left rim of the central trees is carved by the pale sky; the underside of the path turns because a lavender gray rests against a cooler green; the lawn’s edge is achieved by a fast, dark seam followed by a bright swipe of yellow. Where he wants to lock a form, Matisse allows a linear accent to slip through, as at the right edge where a swift graphite-like line suggests a slender trunk. These selective contours act like binding stitches along a textile seam. They keep the brilliant planes from fraying while preserving the primacy of color.

Space, surface, and the modern balancing act

Depth is shallow but convincing. Overlap and the curving path give you near, middle, and far. Yet the forms are pressed forward, and the pattern of strokes refuses to dissolve into deep perspective. The canvas reads as a decorated surface and a place you could walk into at the same moment. That doubleness is the modern achievement here. The garden becomes not only a subject but an engine for reconciling flatness with spatial experience.

The Luxembourg Gardens as a modern motif

Matisse returned to this subject across several canvases from 1901 to 1903 because it solved a practical problem. The park offered architecture that was already half abstract: hedges clipped into cones, lawns cut into bright lozenges, paths that snake like ribbons through bands of trees. It also embodied modern leisure—city dwellers strolling in cultivated nature—and thus aligned with his taste for everyday scenes elevated by pictorial clarity. In this version the figures that sometimes populate the Luxembourg are absent. The result is concentrated, a study of how the cultivated landscape itself can become a rhythmic composition.

Dialogues with predecessors and contemporaries

“Luxembourg Gardens” listens to Monet’s serial parks and Cézanne’s constructive brush, but it speaks with Matisse’s voice. The broken color has Impressionist ancestry, yet the palette is weightier and the value range tighter, closer to Cézanne’s insistence on structure. There are echoes of Gauguin and the Nabis in the occasional dark seam and in the respect for decorative flattening, but the surface never becomes pure pattern. What distinguishes Matisse is the equilibrium of these influences: the decorative and the descriptive remain equal partners, and temperature shifts carry the story of space.

The small blue surprise and the logic of accents

Near the upper right, within the dark conifer mass, Matisse plants a pocket of saturated blue. It reads as a patch of sky glimpsed through needles, but its function is greater than depiction. The blue is a chromatic counterweight to the warm core of the canvas. It prevents the right side from becoming a static wall of green and suggests that air circulates behind the tree mass. Accents like this—small and intense—are how Matisse articulates depth without giving up surface control.

Likely palette and material choices

Only technical study can be definitive, but the harmony suggests a practical kit of the period: lead white mixed with a touch of zinc for the high, cool lights; ultramarine and cobalt to key the sky and cool shadows; viridian or terre verte moderated by ochre for the lawns and deep greens; cadmium yellow and yellow ochre for sunlight and foliage lifts; vermilion or cadmium red for the warm shrub passages; raw and burnt umbers to steady the darks; a trace of ivory black for the most binding seams. Paint handling shifts from opaque impasto in the foliage to thinner, oily scumbles in the sky and path, which allows the surface to breathe.

How to read the picture slowly

Begin with the big forms, allowing the twin tree cones to occupy your field of vision. Notice how the path at your feet becomes the picture’s sentence, curving and modulating the tempo. Let your eye then measure temperature shifts across the central masses, feeling how orange locks with violet, how yellow sits beside a cooler, greenish gray. Step closer and watch individual strokes resolve into leaves and then dissolve back into pure paint. Back away to confirm the overall calm of the light. Each shift of distance produces a new coherence; the painting is built to reward that oscillation.

The work’s place in Matisse’s trajectory

By 1903 Matisse had already made landscapes in which color started to act independently from local description, but this canvas makes the argument more emphatically. It shows him learning how far he can simplify without losing presence, how to substitute temperature for shadow, and how to make rhythm of brushstrokes stand in for botanical detail. Two years later, in Collioure, those lessons would explode into the blazing chords we call Fauvism. “Luxembourg Gardens” is not yet that blaze, but you can feel the kindling stacked and ready.

Meaning and mood beyond description

Although the painting is devoid of human figures, it is not empty. The curving path reads like a movement through time; the clipped trees evoke the human impulse to sculpt nature; the alternation of warm and cool suggests the day’s pulse between sunlit openings and shaded retreats. The mood is one of alert calm. Nothing is sentimental; nothing is harsh. The garden is a place where modern life can rest inside color’s order.

Display and conservation considerations that enhance viewing

The painting’s harmony benefits from mid-neutral surroundings. Too white a wall will over-cool the lilac sky; too dark a room will swallow the deep greens and make the warm middle register shout. Soft, raking light brings out the varied surface, revealing how the brush turned differently in tree, grass, and path. Because the paint includes thinly scumbled passages, glare control is important; a viewer should be able to move slightly and watch the painting’s surface activate without being obscured by reflections.

Why this canvas remains fresh today

“Luxembourg Gardens” endures because it reconciles two appetites that viewers still share: the desire to recognize a place and the delight in seeing paint behave as itself. Matisse offers both without compromise. The park is there, legible, inviting, yet the real subject is the tuned agreement of forms and temperatures. That agreement feels as modern now as it did in 1903, a quiet assurance that clarity and intensity can live together on the same surface.