Image source: wikiart.org

Historical Moment And Why This Picture Matters

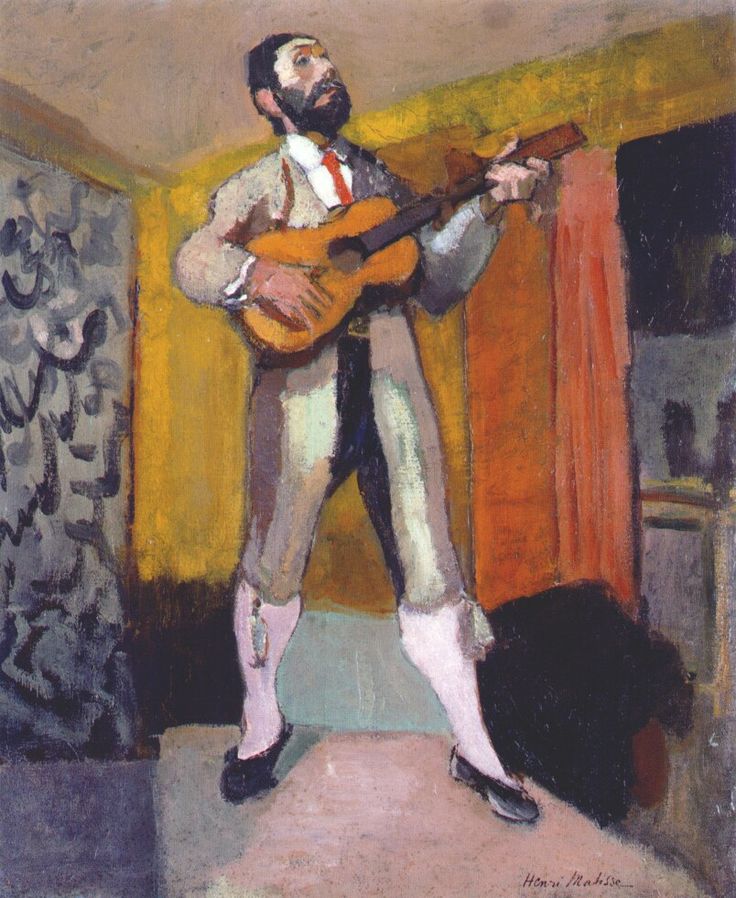

Henri Matisse painted “The Guitarist” in 1903, during a pivotal transition between academic naturalism and the daring simplifications that would culminate in Fauvism a couple of years later. In these years he repeatedly staged musicians in modest rooms because the subject let him test three concerns at once: human gesture as a carrier of emotion, decorative pattern as an equal partner to figuration, and color relations as the primary engine of form. This standing guitarist is one of the clearest statements of that search. It takes the intimacy of a domestic performance and turns it into a compact laboratory where plane, contour, and temperature do the work once done by elaborate modeling and anecdotal detail.

First Impressions: A Room Tuned Like An Instrument

What strikes you first is the clarity of the staging. A bearded performer stands near the center, guitar angled upward, head lifted as if catching an inner pitch. The room is shallow and legible: patterned wall on the left, a mustard-gold partition behind him, a red-orange curtain at the right, and a pale floor that gives the figure a small apron of space. Nothing is busy; everything is bold. You register the scene instantly the way you grasp the key of a song after the first chord. This legibility is not simplification for its own sake; it’s a way to let the eye “hear” the rhythm of forms.

Composition: A Vertical Solo On A Tight Stage

Matisse organizes the rectangle around a tall triangle. The guitarist’s feet splay on the lower edge like a base, the knees and torso form the sides, and the head provides the apex. The raised neck of the guitar pushes diagonally toward the upper right, animating the triangle and preventing the figure from reading as a static column. Three strong verticals—the patterned wall, the yellow partition, and the red curtain—frame the triangle like proscenium wings. The shallow depth compresses stage and backdrop so the figure seems to press against the decorative field, creating a friction between space and surface that is thoroughly modern. Even the light gray floor, a simple trapezoid, works compositionally as a resting field against which the figure’s darker shoes and shadowed calves snap into focus.

Gesture And The Physiology Of Music

Rather than portrait likeness, the picture gives you a body practicing its craft. The left hand climbs the dark fingerboard, knuckles arched; the right hand hovers mid-strum near the sound hole; the shoulders are squared; the chin tilts upward as if listening to the room. The costume—cropped jacket, breeches, pale stockings, red tie—adds a Spanish inflection without tipping into ethnographic detail. The stance matters more than the attire: knees slightly bent, weight distributed evenly, soles gripping the floor. You feel the discipline of playing while standing, the way the whole body becomes a support for the instrument’s resonance.

Color Architecture: Warm Field, Cool Relief, Exact Accents

The palette calibrates warmth and sobriety with care. The right-hand curtain is a charged red-orange; the central wall is a mustard gold that glows without shouting; the patterned panel at left cools the stage with slate blues and grays; and the floor is a tempered, greenish gray that quiets the lower register. The figure unites these fields. Flesh is modeled with ochres and muted pinks cooled by gray-lilac shadows. The suit is largely a cool, pearly gray-green edged by darker seams; stockings are creamy whites that catch the room’s ambient light. The guitar—burnt orange body, dark brown bridge and neck—becomes the warm heart of the picture, a chromatic echo of the curtain and wall around it. Because blacks are rare and whites are never unmodulated, color carries structure through temperature changes rather than brute value jumps, which keeps the whole surface breathing.

Light As Climate, Not Spotlight

There is no single window beam or theatrical highlight. Illumination feels like a calm, general glow within the room. Transitions across the jacket, face, and calves occur through slow temperature modulation, not harsh contrast. Matisse saves his crisply placed lights for strategic places—the glint on the left sleeve, the sheen on stockings, the small planes on the cheek and nose. Those few accents do the work of describing material while leaving the overall climate undisturbed, like bright notes sounding over a drone.

Pattern And Decoration: Partners In The Performance

On the left, calligraphic foliage in inky blue scrolls up the panel; on the right, the curtain’s broad red field holds faint, vertical undulations; behind the player, the gold partition is gently rubbed so undercolors whisper through. None of these passages are descriptive wallpaper; they are rhythmic counters to the figure’s geometry. The patterned panel complicates the profile so the head doesn’t float; the curtain’s vertical mass answers the diagonal of the guitar; the gold plane links the warmth of instrument and curtain while giving the central silhouette a halo of contrasts. Matisse treats decoration as a second performer that harmonizes with the musician’s pose.

Contour And Adjacency: Drawing Without Description

Edges emerge primarily where colors meet. The calf at right exists because creamy stocking abuts a pale floor; the jacket’s shoulder appears where a cool gray meets warm gold; the head is carved from the field by a dark beard mass against yellow. At crucial junctures Matisse reinforces forms with short, assertive contours—around the guitar bouts, along the fingerboard, at the edges of the shoes. These “binding seams” recall the cloisonné outlines of Gauguin and the Nabis, but here they are used sparingly, to keep the heat of the surrounding color from swallowing key shapes. Drawing becomes a structural rhythm rather than a catalogue of details.

Brushwork And Materiality: Notes, Chords, Rests

The handling alternates between dense, loaded strokes and lean, breathing scumbles. The guitar’s body is pushed with buttery pigment so its orange reads as wood catching light. The gold wall is rubbed thin, allowing a living surface where undertones shimmer, like the resonant sustain after a chord. The patterned panel’s motifs are slapped in with quick calligraphy; they read as leaves or flourish only because the surrounding field is so clear. On the figure, touches become more articulated—the cuff’s light, the knee’s rounded plane, the crisp edge of the lapel—so that fabric, flesh, and leather feel distinct without over-explanation. The brush becomes the metronome: brisk on pattern, steady on architecture, emphatic on the instrument and the body that drives it.

Space And Flatness: A Productive Tension

The room is shallow by design. A wedge of floor tilts gently upward; walls press close behind the figure. Yet space never collapses entirely. Small cues—the cast shadow near the feet, the overlap of guitar over jacket, the occlusion of panel by curtain—keep you convinced. This balance between believable depth and declared surface is the hinge of Matisse’s modernity. He wants you to feel a room and at the same time to see a composed field of color-planes locked together on a rectangle.

Rhythm And Musicality: Hearing With Your Eyes

Without resorting to motion blur, Matisse makes music visible. The diagonal of the neck points like a melody line; the splayed feet beat time at the base; repeated verticals act like a steady bass; the curve of the guitar’s bouts rhymes with the rounded shoulders and the small arcs inside the patterned panel. Even the red tie functions like a bright, recurring motif threaded through the suit’s grays. You enter the picture at the shoes, move up the legs to the guitar, slide along the neck to the player’s lifted chin, and then drift to the curtain and back—an eye-path that mirrors the physical mechanics of strumming and listening.

Dialogues With Precedents And Peers

This painting trades with several lineages without belonging to any one of them. From Manet comes the authority of broad, unblended planes that refuse busy illusionism. Gauguin and the Nabis contribute the occasional dark contour and the conviction that pattern can be structure. Vuillard’s intimate rooms and Degas’s performers linger in the background, but Matisse’s temperament is different: he drains anecdote, reduces optics to climate, and trusts a few tuned shapes to carry both description and emotion. The Spanish flavor of the costume is not ethnography; it’s a chromatic key that legitimizes passionate reds and oranges inside a Paris studio.

Likely Pigments And Practical Craft

While specific analysis belongs to conservators, the harmony suggests a practical turn-of-the-century kit: lead white for high keys; yellow ochre and raw sienna for wall warmth and flesh undertones; cadmium or vermilion reds for the curtain and guitar body; ultramarine and cobalt for the cool panel motifs and minor shadows; viridian or terre verte nudged with ochre for suit greens; raw and burnt umber for grounding darks; and a prudently used ivory or bone black for the sharpest contours. Paint weight is varied intentionally: thin scumbles to keep walls breathing, richer impasto to energize the instrument and the garment’s lights. These material decisions are not backstage trivia; they are audible in the final chord the canvas sounds.

The Ethics Of Omission: Leaving Space For The Viewer

Matisse leaves out everything that would slow the eye. No fret markings, no wallpaper repeats counted stitch by stitch, no shiny shoe laces, no mapped beard hairs. Even the face is reduced to a few planes—cheek wedge, brow facet, dark beard, a quick stroke for the eye. The omissions aren’t shortcuts; they are discipline. By keeping only what serves the harmony of the whole, he ensures that the viewer’s attention cycles through the essential relations of color and shape—the true subject of the work.

Reading The Picture Slowly: A Short Guide

Start by letting the big architecture settle: trapezoid of floor, three wall fields, central triangle of the figure. Then, track the warm-to-cool dialogue—the guitar’s orange to the curtain’s red-orange to the yellow partition, cooled by the slate panel and the suit’s grays. Approach the edges and notice how forms are authored by adjacency: stocking against floor, cheek against wall, guitar against jacket. Pause on the few crisp highlights that declare material—the enamel-like light on the stocking, the tiny shine on the cuff, the glint at the guitar’s rim. Finally, step back and feel the rectangle as one climate where everything seems to sound at once. The more you move between near and far, the more coherent the music becomes.

Meaning: A Modern Creed Of Harmony

Beyond the descriptive pleasure of a musician in a room, “The Guitarist” proposes a belief about painting and, by extension, about life: harmony comes from tuned relations, not from ornate additions. The decorative and the observed can coexist without hierarchy; the warm and the cool can stabilize each other; gesture can be clear without theatricality. The picture feels “true” not because it catalogs facts but because its structures agree—color with line, plane with light, figure with field. That agreement is Matisse’s version of musical consonance.

Position In Matisse’s 1903 Trajectory

Seen alongside contemporary landscapes, studio corners, and other guitarist variations, this canvas shows Matisse refining the armature that will support his later eruptions of color. He is learning how to keep intensity calm, how to let pattern carry the same weight as anatomy, and how to make depth serve the surface rather than dominate it. Two years later he would push chroma to the edge in Collioure; those Fauvist canvases feel inevitable because works like this proved he could hold a picture together with a handful of planes and a steady climate of light.

Why “The Guitarist” Endures

The painting endures because it extracts grandeur from the ordinary. A small room, a man with a guitar, three walls and a floor: that’s all. Yet the result is full—of rhythm, balance, and inner glow. It gives you the feeling of a chord still vibrating after the last stroke, of color that warms without shouting, of design so clear it feels inevitable. In that clarity you glimpse Matisse’s larger promise: that painting can be music for the eyes, and that the simplest materials—red, gold, gray, a human stance—can carry a deeply modern grace.