Image source: wikiart.org

Historical Context And Why This Paris Park Scene Matters

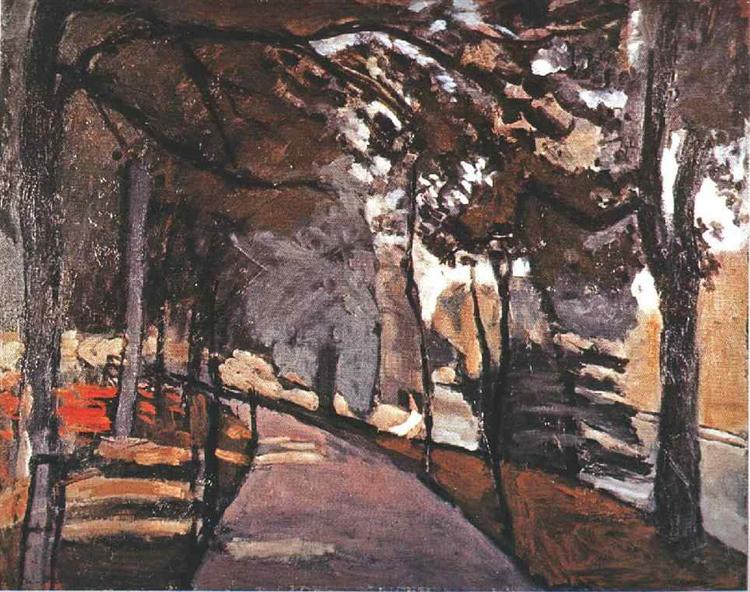

Painted in 1902, “The Path in the Bois de Boulogne” finds Henri Matisse on the cusp of the chromatic audacity that would soon define Fauvism. A year earlier he had experimented with saturated still lifes and landscapes; a year later he would push color to blazing extremes. This canvas sits at a revealing hinge. Instead of fireworks, Matisse embraces a low-key autumnal chord and tests how rhythm, structure, and touch can carry a picture even when chroma is subdued. The subject—a promenade under dense trees in Paris’s vast western park—was familiar to the city’s flâneurs and a favored motif for modern painters. Yet Matisse does not treat the Bois as a picturesque postcard. He makes it a laboratory for movement through space, for the dialogue between decorative flatness and believable depth, and for the tonal music of browns, grays, and umbers accented by sudden flickers of light.

First Impressions: A Tunnel Of Trees And A Road That Pulls You In

At first glance the painting reads as a canopy of branches forming a vaulted tunnel over a path that recedes into a misty distance. The trunk at the far right becomes a strong vertical boundary, while slimmer trunks rhythmically pace the left side. The path opens at the lower center and narrows toward a pale wedge of horizon, where light leaks through the foliage. Patches of rusty red and warm ochre appear like benches, leaves, or glimpses of sun on gravel. The overall sensation is of an enveloping passage, a walk where darkness and glow alternate every few steps, and where the viewer’s body is gently recruited into the forward motion.

The Composition’s Armature: A Corridor Built From Repeating Vertical And Diagonal Rhythms

Matisse organizes the rectangle with a precise architecture of lines and masses. Vertical trunks beat like posts along the sides, framing an elongated trapezoid of roadway. The diagonal of the path’s right edge is particularly commanding, slicing from the foreground to the center and establishing momentum. Overhead, the boughs knit together in a ceiling of angled strokes, a dark arch that both protects and slightly presses down upon the space. These elements create a corridor effect—an outdoor nave—so that the viewer proceeds under an arboreal vault toward a soft, luminous apse. The compositional clarity is striking: even in dim light the route is legible, and even with sparse detail the scene feels complete.

Tonal Design: A Low-Key Chord That Breathes

Color in this canvas is restrained, almost monochrome, yet never dull. The range runs from deep umbers and espresso browns through olive blacks and smoky grays to pale, chalky lights. Against this subdued register, small sparks—burnt orange notes at the left, a warm beige aperture deep in the tunnel, a whitish edge along a trunk—flare like embers. Because Matisse avoids dead blacks and pure neutrals, every dark carries a hint of hue. The canopy’s shadow is not a void; it is a living mixture that allows nearby warms to glow. The result is a nocturne-like harmony whose vitality lies in temperature shifts more than in hue contrast.

Light And Atmosphere: A City Park As Weather

Rather than staging a dramatic spotlight, Matisse describes light as weather. The path brightens and dims as if the clouds were moving; the middle distance dissolves into a haze that suggests moist air under heavy leaves; the far opening shows a pale, diffused glow rather than a hard sunburst. This approach heightens the sense of time—late day or early evening, perhaps in autumn—and gently mythologizes a modern place. The Bois de Boulogne becomes not just a park but a climate, a shared atmosphere connecting trunks, path, and passerby.

Brushwork: From Knitted Canopy To Earthen Floor

Touch varies to suit material. The foliage is laid with compact, interlocking strokes, forming a knitted fabric of paint that mimics the visual tangle of leaves without counting them. Trunks are struck with dense, knuckly marks that convey bark’s weight, then softened in places to imply humidity and movement. The path is built from broader, flatter swathes that sit evenly and read as a traversable surface. Where light breaks through, Matisse scumbles thin, pale paint, allowing the canvas grain to catch and sparkle like sky glimpsed between branches. The alternation of tight and loose, thick and thin, keeps the surface alive and assigns a tactile “speed” to each zone.

Drawing By Adjacency Rather Than Outline

Edges arise where tones meet rather than where lines are drawn. A trunk is “drawn” by the push of a dark column against a slightly lighter ground; the path’s edge is the collision of warm ochre and a deeper brown-red; the far opening is authored by the meeting of pale light and smoky canopy. Where a line does appear—a slim rib of dark riding a trunk, a rail-like accent along the left—it is calligraphic and immediately reabsorbed by neighboring strokes. This method preserves unity. The painting remains a single fabric of decisions rather than a colored-in drawing.

Space: The Tug Between Decorative Flatness And Persuasive Depth

Matisse compresses and expands at once. The arching canopy and the large foreground trunks insist on surface: they form near-vertical screens and broad, flat patterns that press against the picture plane. The path, by contrast, opens a recession that feels bodily and convincing. This tension between flat pattern and deep corridor is not a flaw—it is the point. It lets Matisse keep faith with modern decorative clarity while still offering the kinesthetic pleasure of walking into the picture. The Bois is both a design and a place, a carpet and a road.

Movement And The Viewer’s Route

The canvas teaches a lucid route through its forms. Most viewers enter along the path in the foreground, follow the right-hand edge as it pivots, glance at the flare of pale light beyond, and then drift up into the canopy where the strokes ricochet laterally, bringing the gaze back to the front. The beat of the trunks works like a metronome for this journey. Subtle interruptions—the orange bench-like notes, the paler stones at the path’s center—act as stepping-stones. The painting thus becomes a choreography: steady advance, momentary pause, breath in the open glow, return under the trees.

Thematic Resonances: Urban Leisure, Solitude, And Modern Time

The Bois de Boulogne was a nineteenth- and early twentieth-century emblem of Parisian leisure—a place for promenades, carriages, conversations, and courtships. Matisse chooses not to populate his scene with figures. The absence does not negate sociability; it concentrates the universal part of the experience: the rhythm of walking, the psychological shelter of a tree tunnel, the companionship of filtered light. The path becomes an emblem of modern subjective time—minutes counted not by clocks but by steps, benches, and passing patches of brightness. The painting’s hush contains the memory of crowds without the noise.

Dialogues With Predecessors And Peers

The work listens to a lineage and answers in a new accent. Corot’s park scenes and the Barbizon painters’ forest interiors taught the poetry of subdued chords and filtered light. Monet and Pissarro mapped modern Parisian parks in flickering high key, privileging optical vibration. Cézanne’s constructive brushwork showed how mass could be built from planar strokes. Matisse absorbs all three and turns them toward his own goals. He keeps the low-key hush of the Barbizon mood, the modern subject of the Impressionists, and the structural economy of Cézanne—but he simplifies further, risking large patterns and near-abstract rhythms that anticipate the Fauves’ clarity.

Materiality And Likely Pigments

The palette’s earthiness suggests abundant use of natural pigments: red and yellow ochres for path and foliage, raw and burnt umbers for trunks and deep shadows, bone or ivory black moderated with ultramarine to keep darks chromatic, and lead white scumbled into the light apertures. Subtle olive notes may come from viridian tempered with ochre. Paint sits in alternating registers: lean scumbles where the air must breathe, tackier masses where trunks need authority. A few scraped passages reveal underlayers and allow the canvas weave to participate in the shimmer of light.

The Role Of Omission

Minimal detail is a deliberate ethic here. No leaves are counted, no bark is catalogued, no faces appear on benches. The railing is only hinted, the path’s gravel suggested by directional swathes. Such omissions are not gaps; they are protections for the whole. By refusing anecdotal distractions, Matisse keeps the painting concentrated on structure, movement, and atmosphere. The viewer’s memory and bodily knowledge of walking under trees fill in what is not explicit.

How To Look Slowly

Begin by allowing the large relations to settle: the dark overhead canopy, the pale wedge of distant light, the diagonal of the right-hand path edge, the beat of vertical trunks. Once the composition holds, move closer and follow how edges form by adjacency—dark against slightly less dark, warm against cool. Linger on the scumbled lights that breathe through the foliage and on the reddened notes that punctuate the left side. Step back again and let the corridor open; feel your eye take steps along the path. That near–far rhythm is the painting’s pleasure and the key to its making.

Relation To Matisse’s 1902 Suite

Placed beside Matisse’s cool blue views of Notre-Dame from the same year, this park scene looks like a quieter cousin, more earthbound and introspective. Where the cityscapes test a unified cool palette and the frame of a window, this picture tests a unified warm-earth palette and the frame of trees. Where his still lifes of 1902 explore how omission and scumble can unify a tabletop, this painting applies the same method to open air. In every case the goal is the same: let color relations and rhythmic structure, not descriptive minutiae, carry the weight of representation.

Enduring Significance

“The Path in the Bois de Boulogne” endures because it distills an everyday modern experience into a persuasive visual music. A handful of darks, a few apertures of light, and a disciplined rhythm of trunks are enough to rebuild a whole walk. The painting proves that Matisse’s modernity is not synonymous with high-voltage chroma. Even in a nocturne key he can make a surface breathe, a space open, and a mood linger. The picture offers the rare mixture of calm and forward motion: you feel at rest inside it, yet the path keeps inviting the next step.