Image source: wikiart.org

Historical Context And Why This Still Life Matters

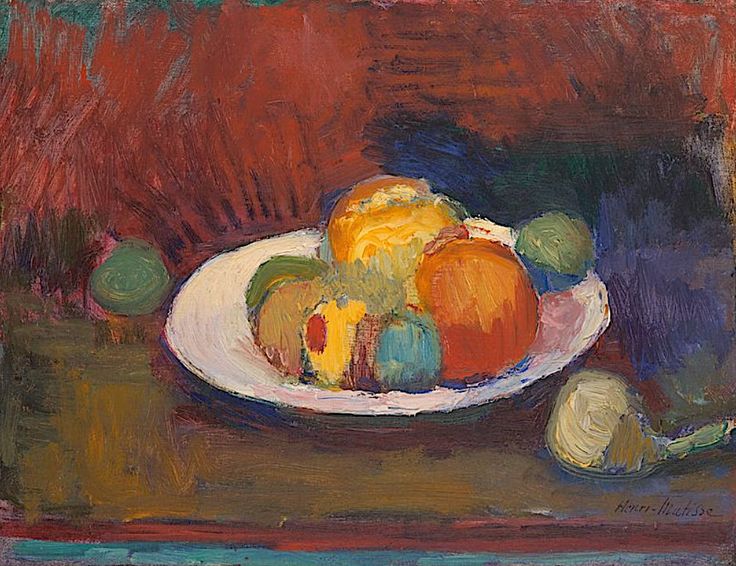

Henri Matisse painted “Fruit Dish” in 1902, during the crucial transition between his rigorous academic training and the color-led language that would soon erupt as Fauvism. Still life was his ideal laboratory. Fruit offered solid, legible forms that could withstand bold simplifications; a tabletop provided a stage where he could orchestrate planes of color, temperature contrasts, and edge relationships without the demands of portrait likeness or landscape perspective. In this canvas he strips the scene to a few essentials—a white plate, a mound of fruit, a compressed interior—and proves that color relations, not intricate detail, can carry structure, light, and mood.

First Impressions: A Stage Of Heat And Cool Around A White Plate

The painting hits the eye as a compact drama: a white dish centered slightly low in the rectangle, heaped with oranges, apples, and perhaps a lemon, all pressed forward by a hot red-brown wall and stabilized by a dark, olive tabletop. The background is not a passive backdrop; it ripples with vertical and diagonal strokes that radiate from behind the plate like an afterglow. The fruit mound reads as a single volume whose surface oscillates between warm orange, citron yellow, and cool blue-green. Smaller fruit roll toward the edges, echoing the central colors while enlarging the sense of space. Everything is simplified to planes and patches; nothing is fussed, yet the arrangement feels abundant and complete.

Composition As A Clear Armature

Matisse builds the rectangle with three horizontal belts: a narrow turquoise lip at the very bottom, a broad, olive-brown tabletop carrying the plate, and a high red-brown wall. These bands keep the painting grounded and declare it an interior. The plate sits slightly left of center and low enough to let the fruit rise into the middle third, where the eye naturally rests. The elliptical rim creates a quiet oval inside the larger rectangle, while the heap of fruit stacks as a soft pyramid. A few outliers—a pale pear at right, a green fruit at left—prevent symmetry from congealing and nudge the viewer’s gaze in a slow loop around the dish. The composition is modest in ingredients and exact in proportion, inviting contemplation rather than spectacle.

Color Architecture And The Prelude To Fauvism

Color does the structural work. The background is a high, warm register built from iron oxide reds and touches of violet that are scumbled thinly so the canvas breathes. The tabletop’s olive and umber counterweight cools the warmth and supports the white plate. On the dish, saturated complements spar: cadmium oranges and yellows face off against bluish greens and teal shadows. Darks are chromatic, not dead—wine-violet and deep blue sit in the plate’s shadow and fruit seams—so the whole chord vibrates rather than dulls. There are almost no neutrals; every mixture leans warm or cool, which is Matisse’s hallmark in these years. Temperature, not tonal modeling, builds form.

The White Plate As Optical Engine

The plate’s whiteness is not a blank; it is a field of small temperatures. Matisse cools one side with lilac and blue notes where shadow collects and warms the other with butter and cream where reflected light lifts the porcelain. The subtle band of blue along the outer rim pushes it forward against the tabletop; a violet seam on the underside glues it back down. Because the surrounding colors are so saturated, the plate acts as the canvas’s optical engine: it compresses every hue in the room and throws them back to the eye in one breath.

Modeling Fruit Through Temperature, Not Shadow

Look at the orange on the right: instead of a traditional highlight-to-shadow cone, it turns with temperature. Warm orange swells into the light, then cools into red-violet near the contact shadow; a few short blue strokes kiss its lower edge where the plate’s reflected cool climbs the rind. The lemon at center gathers light in dense, buttery strokes and cools to mint where it faces the table. The green apples contain small eruptions of red and yellow, proof that Matisse prefers relational accents to single-note “local color.” Every piece reads convincingly because its temperatures are tuned to neighbors, not because any one object has been exhaustively described.

Brushwork And The Feel Of Materials

Touch varies to register what things are made of. The wall is knitted from brisk, vertical-lilt strokes that stack like woven fabric; the tabletop carries longer, flatter pulls that feel wooden and dense; the plate is handled in short, circular notes that suggest glazed porcelain; fruit surfaces thicken into creamy dabs and directional swipes that echo the way rind and flesh catch light. Paint is sometimes dragged thin so the weave shows, sometimes laid body-thick so it catches literal light. That orchestration of speeds—fast wall, steady table, lively fruit—turns the act of looking into a felt rhythm.

Drawing By Adjacency Rather Than Outline

Edges arise where colors meet. The plate’s ellipse is “drawn” by the collision of off-white and olive; the orange’s contour exists because orange presses against a cool shadow; the pear at right appears as a pale body cut by a blue-violet seam. When Matisse deploys a line, it is calligraphic and brief—a rim accent, a crease in the fruit, a fissure on the table—immediately absorbed back into the surrounding color. The picture does not feel like a drawing that has been colored; it feels like a world precipitated from tuned patches.

Space Compressed Into A Decorative Field

Depth is plausible but shallow by design. The table does not drill back into perspective; it sits as a plane that lifts slightly toward the wall. The wall itself remains a flat, breathing cloth. The plate and fruit read as forward, yet never pop out of the picture plane. This compression serves Matisse’s decorative ideal: the painting must first be a balanced arrangement on a flat surface before it is a window. That conviction allows the color chord to stay tight and legible at a glance.

Light As Ambient Weather

There is no single directional spotlight. Illumination is ambient, as if a window outside the frame floods the room. Cast shadows are abbreviated; reflected color takes their place. Blue creeps into the plate’s underside; green from the apples cools the lemon’s shadow; violet from the wall settles into the table near the dish. Light becomes a network of relations rather than a theatrical effect. This approach keeps the harmony intact and prevents any one object from dominating by contrast alone.

The Table’s Near-Black As Living Color

The darkest passages—beneath the plate and at the front edge—are not voids. They are mixtures of umber, deep green, and violet that behave like active colors, making the surrounding oranges and whites flare. Matisse will lean on this lesson repeatedly in the next few years: black and near-black can be among the most chromatic notes in a painting when they are tuned and placed properly.

Dialogue With Tradition And With Modernity

“Fruit Dish” nods to the still-life lineage—Chardin’s dignified restraint, Cézanne’s constructive patches, Manet’s insistence on surface—while traveling decisively toward modern color. Where Cézanne probes with analytic tension, Matisse relaxes into harmony. Where Manet relies on value contrasts, Matisse trusts temperature. Where the Nabis flatten in decorative pattern, he keeps the sensation of light moving across objects. The result is neither academic nor purely decorative; it is a poised modern synthesis.

Materiality And Period Pigments

The palette likely includes lead white massed into the plate and highlights; cadmium yellow and orange for the lemon and orange; cobalt and ultramarine in the blue shadows; viridian and emerald for the apples moderated with yellow lakes; alizarin or madder in the red accents; earth umbers and siennas for the table and wall, warmed and cooled by glazes. Matisse alternates thin scumbles—which let the canvas’s tooth sparkle through—with compact, buttery strokes that reflect real light. Those material differences are not garnish; they create the sensation of porcelain gloss, rind pucker, and felted wall all in the same small field.

Rhythm And The Viewer’s Path

The picture invites a looped journey. Many eyes enter at the bright lemon crest, slide to the orange, step through the cool apple cluster, orbit the plate’s rim, pause at the pale pear to the right, and then cross the front edge back to the center. Along the way, correspondences click: a violet in the wall echoing the plate’s underside; a strip of teal on the rim rhyming with apple cools; a red spark in the fruit repeating, faintly, in the background weave. That repetition knits the surface; the route is pleasurable because the painting has been tuned for it.

Omission As Clarity

Matisse withholds specifics: no patterned tablecloth, no knife or glass, no counted leaves, no reflective highlights mapped meticulously. These omissions concentrate meaning. Without story props the eye attends to relations—how a cool stroke turns a warm mass, how a dark seam settles an object on a surface, how a few degrees of temperature shift make porcelain feel round. The still life becomes not a pantry scene but a demonstration of pictorial truth.

How To Look Slowly And Profitably

Stand back first and receive the big chord: hot wall, cool table, white plate, fruit mound. Let those four actors settle. Move closer and watch edges form by adjacency; trace how the plate’s blue rim leans the dish forward; look for small reflected colors—orange warming a neighbor’s shadow, green cooling a lemon’s edge. Step back again until all these local events fuse into one calm, glowing arrangement. That near–far oscillation reenacts the painter’s own process: patch, compare, adjust, and then check the whole.

Relationship To Matisse’s 1901–1902 Still Lifes

Compared with the saturated fireworks of “Dishes and Fruit on a Red and Black Carpet” (1901), “Fruit Dish” is more compressed and interior, with a stronger emphasis on the table-wall stage. Compared with the quiet poise of the 1902 “Bouquet of Flowers in a Crystal Vase,” this painting pushes complementary heat harder, letting oranges and blues clang in the center while the wall radiates warmth. Across all of these works, the same grammar rules: color carries structure, black is a living neighbor, edges are authored by contact, and omission protects harmony.

Why “Fruit Dish” Endures

The canvas endures because it turns a small, familiar subject into a complete lesson in modern picture-making. It shows how a white plate can become an engine for an entire color system; how fruit can be modeled by temperature rather than by theatrical light; how a background can act and breathe instead of merely sitting behind; and how a painting can remain flat and designed while still feeling full of air. More simply, it is a pleasure to look at: a heap of ripe color resting on a dark table, glowing as if it had saved the daylight and was giving it back.